Jacques Rivette | 2hr 1min

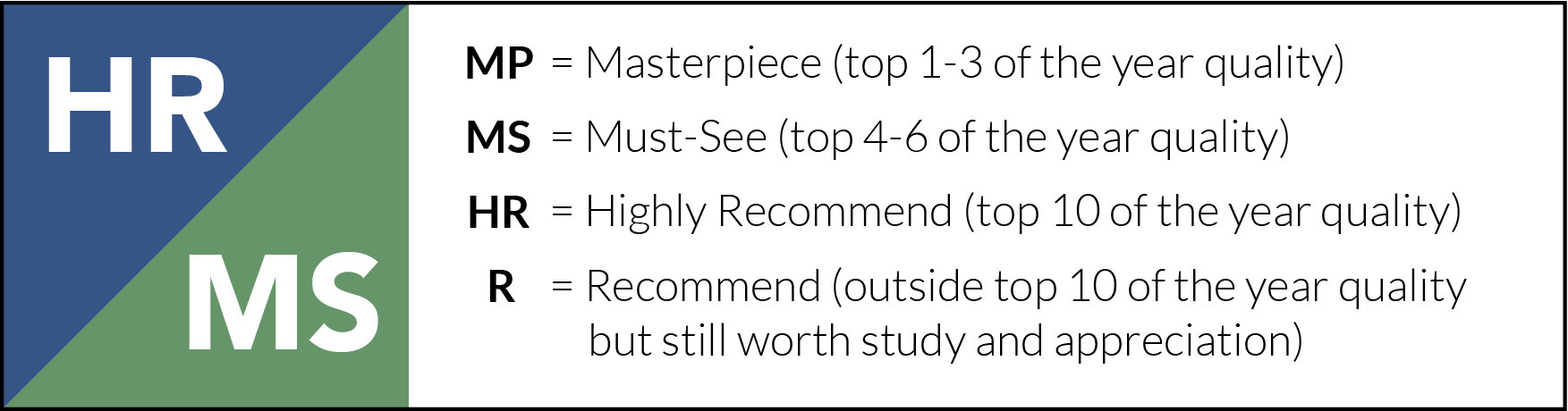

It wouldn’t be hard to believe that each location in Duelle is interconnected within some giant, labyrinthine complex, entangling its human characters in an enigmatic web of manipulation and deceit set up by two warring goddesses. Besides their archetypal representations as opposing forces of nature, the Queen of the Sun and the Queen of the Night are not so different in their common goal – to claim the mystical Fairy Godmother diamond as their own, and use its power to spend their remaining lives on Earth as mortals. The premise of this high-concept fantasy wouldn’t seem out of place in ancient mythology, but given Jacques Rivette’s roots in the French New Wave one should not expect such a clean narrative. Duelle is as much an obscure spin on a film noir mystery as it is a whimsical fairy tale of extraordinary stakes, transforming 1970s Paris into a battleground for its quarrelling entities.

Rather than any hardboiled Philip Marlowe character tracing down loose threads though, Rivette situates Lucie the hotel night porter as our amateur detective, linking up with taxi dancer Elsa and her brother Pierrot to investigate the conspiracy of the mysterious Lord Christie and his priceless gem. With this gender subversion, Rivette adds another fascinating dimension to this ensemble – any of our four leading women could slot in as Duelle’s manipulative femme fatale. Goddesses Viva and Leni are both fully aware of their genderfluid power too, playing to their feminine sexuality when seducing Pierrot, and dressing in traditionally male, sharp-cut suits as they flirt with Lucie and Elsa.

The tension generated by these interactions is surreal in their obscure subtext and mannered performances, lulling us into a sleepy, poetic reverie. The cumulative effect is both intoxicating and distancing, letting us feel as if we are looking through a window into an alternate world that escapes the rules of our reality, rendering us powerless. Elsa cryptically lyricises as much in one crucial metaphor too.

“Dreams are the aquarium of the night.”

When Rivette visually manifests this imagery as the backdrop to a meeting between Leni and her ill-fated victim, a murky ethereality takes hold. Fish and turtles lazily drift through the water behind them, which diffuses a green light into the surrounding atmosphere, illuminating gods and mortals alike in an unearthly glow. As the scene progresses, Rivette’s camera continues to circle the aquarium in slow movements, as if similarly moving through a mystical, underwater realm that refuses to release those under its time-slowing spell.

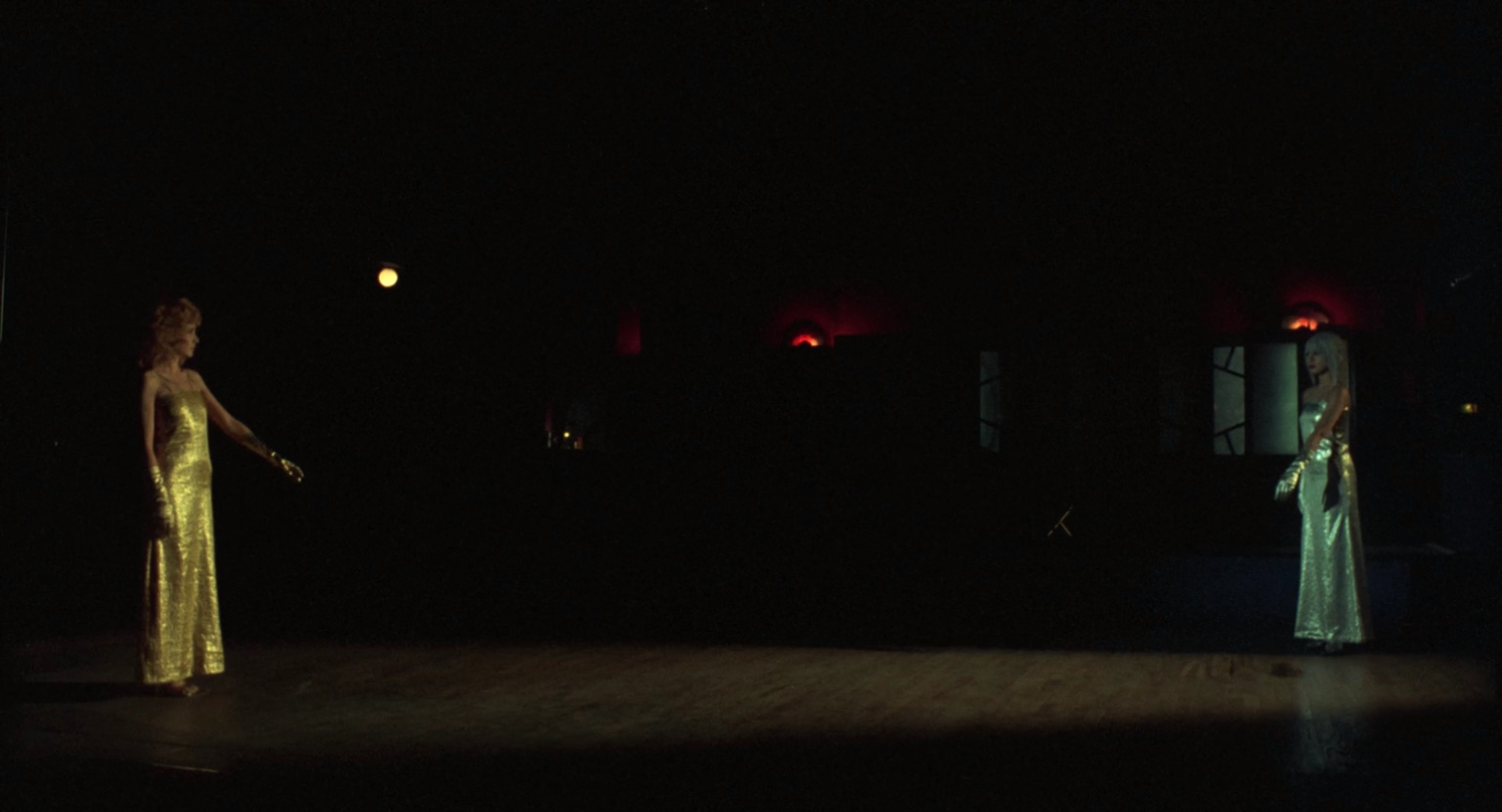

It is a remarkable command over cinematic visuals that extends throughout the rest of Duelle too, made even more impressive by the fact that Rivette is largely shooting on location across Paris’ urban landscapes, imbuing his dark fantasy with a seemingly paradoxical authenticity. Through racetrack centres, underground stations, shady hotels, and lush greenhouses, his camera floats with unhurried ease, basking in the verdant colour palette that he weaves through his lighting and production design. Whenever the opaque plotting escapes us, it is all too easy to fall into the mesmerising atmosphere instead, much like the crowds who move through settings as hypnotised zombies. Ignorance has evidently trapped the world in a state of monotonous routine. Around baccarat tables, gamblers silently rake in chips and smoke cigarettes, while in the background of a burgundy-coloured club, couples sway in synchronicity to the sound of a jazz pianist.

How curious it is too that this musician seems to be virtually omnipresent throughout Duelle, appearing in private hotel rooms, bars, and dance studios alike to accompany scenes with his diegetic improvisations. He is not so much a silent witness as he is a ghostly embodiment of Rivette’s lucid dream, revealing the strings behind the scenes that shape our psychological experience, yet never intruding so much as to break our total immersion.

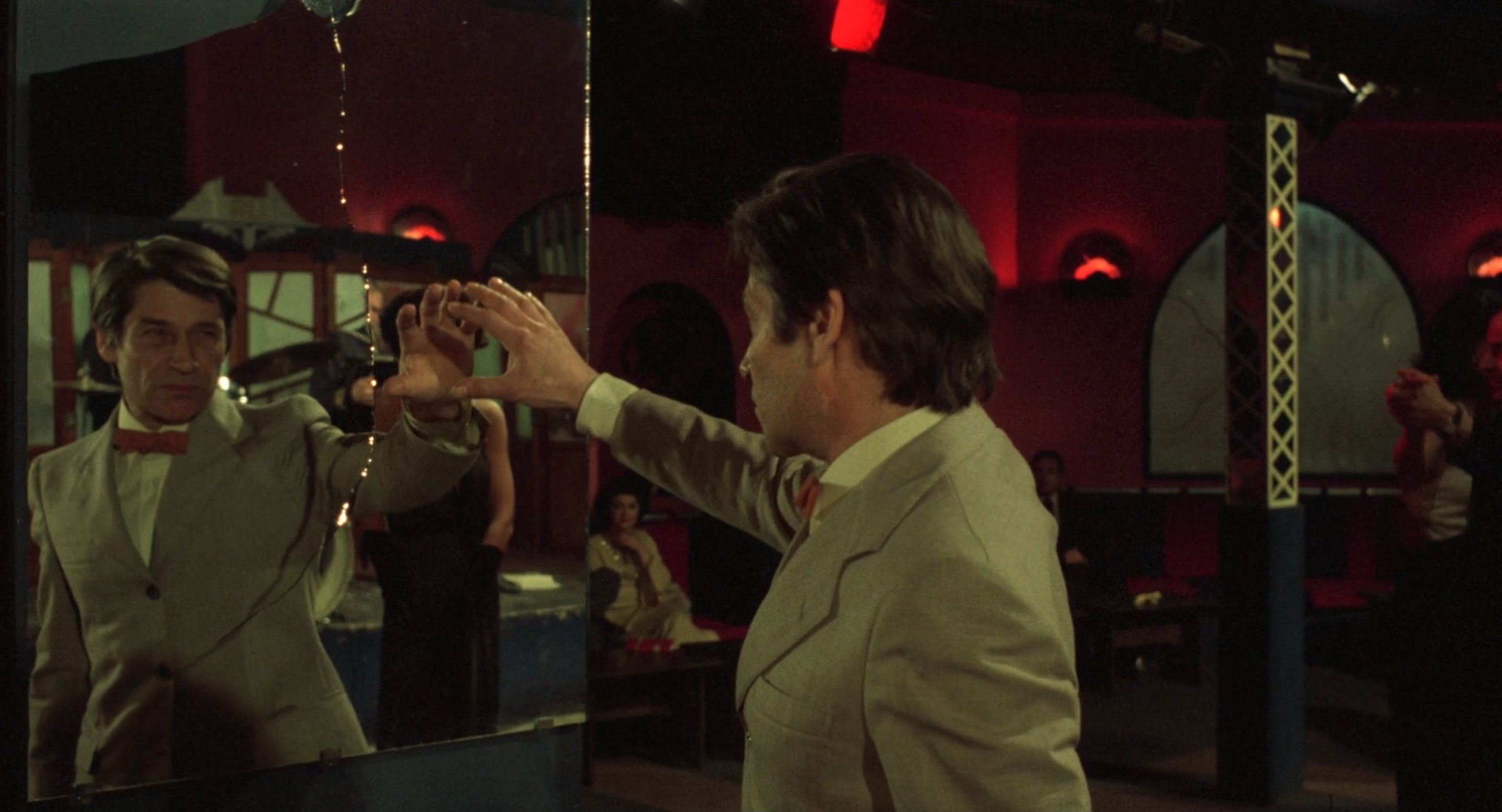

It is a fine line that Rivette is walking on virtually every level of his filmmaking here, simultaneously inviting us into his phantasmagorical mystery while keeping us at just enough of a distance to recognise its deceit. With one foot in reality, we see gods take human form and walk through familiar streets, and with the other foot in a beautifully unstable dreamscape, we see humans as warped refractions of themselves. Mirrors populate his mise-en-scène at every turn, subtly hinting at a world existing beneath our own in tremendously layered compositions, and it is only when Pierrot shatters one that the illusion breaks entirely. Suddenly, the secret identities of both goddesses are stripped away, and seeing each other for who they are, they challenge each other to one last duel.

Parallel to this escalating conflict, Rivette laces a series of formal cutaways that build to a subtle crescendo, keeping the night sky’s waxing moon in our sights. For as long as it is partially impeded by darkness, the astrological powers holding the world in its spellbinding thrall cannot reach their maximum potential. Only when Lucie vanquishes Viva with the diamond does it shine its full, bright light down upon the Queen of the Sun’s defeat, before a brightening dawn illuminates the Queen of the Night’s subsequent downfall. Harmony is finally found in Duelle’s whimsical, elegiac poetry, simultaneously restoring the cosmic cycles of creation, and keeping intact the intransient magic that simmers beneath the most inconspicuous corners of modern society.

Duelle is currently streaming on Mubi.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1970s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: 26 Popular Movies That Aren’t Available to Stream Anywhere – Next Movie Stop