Buster Keaton | 1hr 14min

In a world of overwhelming natural forces seeking to overcome Buster Keaton’s stone-faced romantic, the added threat of an entire family out for his blood only complicates matters further – not that he is entirely aware of the danger closing in on him. When Willie McKay falls for Virginia Canfield, a young woman he meets on the train back to his hometown, he does not know the true extent of the long-running feud between their families. Ever since he was sent away to New York as a baby twenty years ago, his upbringing has sheltered him from the knowledge their continued animosity, making this Southern American village a very dangerous place indeed for the heir to the McKay estate. If there is going to be any saving grace in a situation as tense as this, then it is the Canfields’ unwavering code of honour towards guests, ironically granting Willie sanctuary for as long as he is in the home of his enemy.

Much like Keaton’s great comedic masterpiece The General from a few years later, Our Hospitality finds its inspiration in American history. The Hatfield-McCoy feud stretched multiple decades in the latter half of the 19th century, and although it becomes the subject of Keaton’s satire here, its politics couldn’t be of less interest to him. Right from his opening intertitles, he brushes off any attempt to derive meaning from their feud with a simple dismissal of their mutual hatred.

“Men of one family grew up killing men of another family for no other reason except that their father had done so.”

As a result, all we are left with in the present day are the giant egos of small men, bound by traditions that only drive them deeper into their blind convictions. Keaton doesn’t hold back from confronting the dire stakes at hand, quite unusually sapping his prologue of all humour and drenching it in a vicious thunderstorm as the two family patriarchs shoot each other dead. It isn’t until he turns up as the happily oblivious Willie McKay that Our Hospitality takes a lighter turn, whisking him through various mishaps as he rides a tiny steam train across America towards his inherited estate.

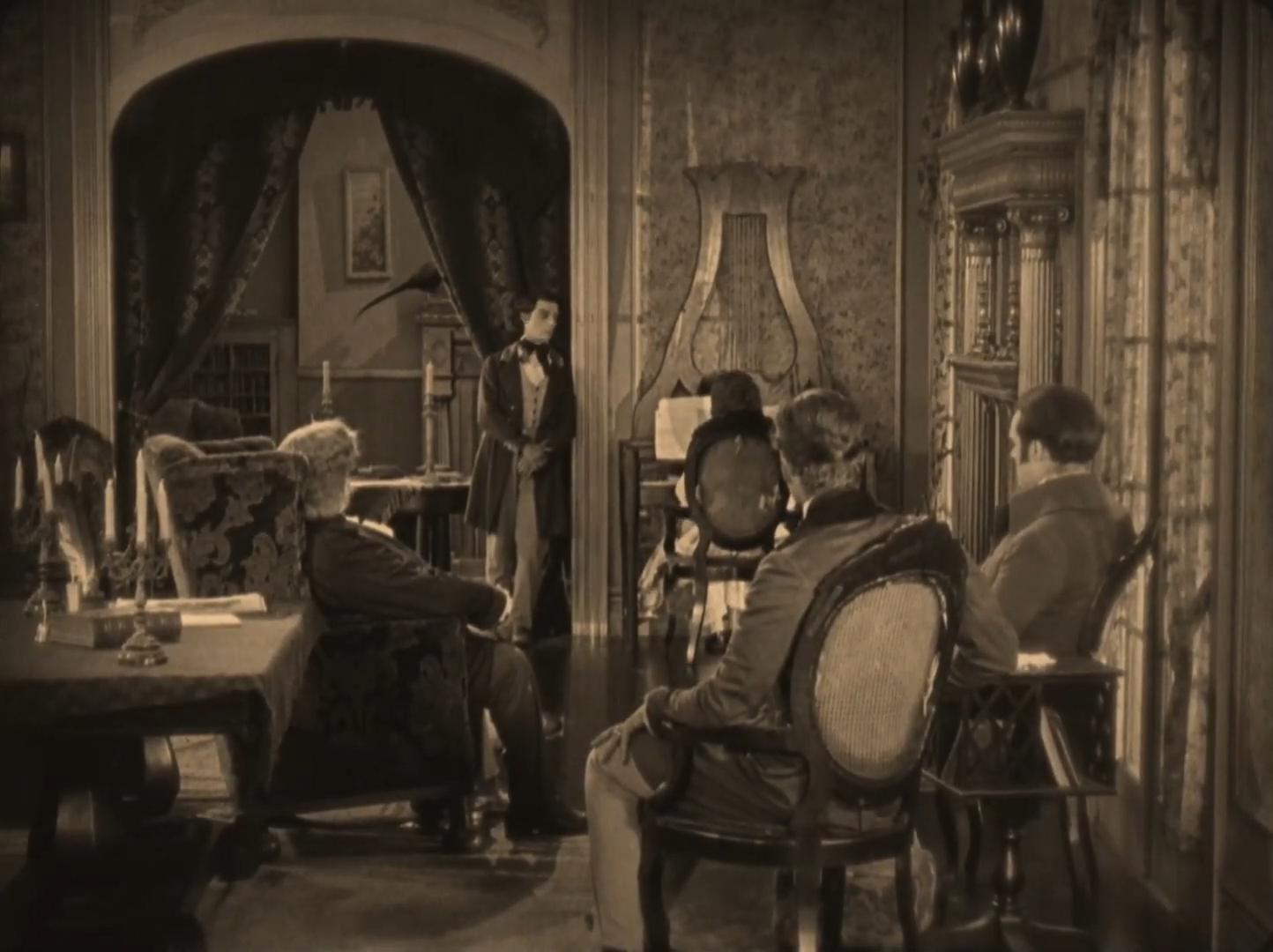

Both this film and Three Ages may mark Keaton’s first features, but by 1923 he had already spent years refining his art as a director and actor of short comedies, effectively setting him up next to Charlie Chaplin as a master of visual comedy. So too had his personal fascination with locomotives been established during this time, as here he continues to bounce physical gags off these giant symbols of modernity and progress. Crooked railways toss passengers up and down, wheels fall off, and carriages are split apart at a crossroads, yet his stoic vehicles relentlessly chug along at their own steady pace, indifferent to those caught up in its chaos.

What Chaplin never quite got the hang of though which Keaton takes to with ease in Our Hospitality is the enormous potential of the camera in framing these gags, frequently setting us back in wide shots to appreciate the dramatic irony unfolding across each layer of the image. As the train driver thoughtlessly kicks back in the foreground, Keaton squares up his shot to catch the rogue carriages that have broken free behind him, making their way down a parallel track. Later when Willie tries to escape the Canfields disguised as a woman, Keaton once again angles his camera from a distance to catch the back of a frock and umbrella, only to reveal the horse that he has dressed up and put in his place just as it turns to the side. This visual comedy is just as much about the creative conception as it is the perspective taken, abiding by a strict set of cinematic rules. If we can’t see something in the frame, then neither can his characters. If his characters can’t see it, then we still might catch the punchline just behind their turned backs.

It is also through these stylistic devices that Willie remains so clueless to the Canfield brothers’ attempts to murder him, drawing out the tension of their one-sided conflict through the walls that divide them. For a time, he is only getting by on pure luck and blissful ignorance, right up until Virginia invites him home and inadvertently grants him protection as a guest. When the recognition of his perilous situation sets in though, the whole world suddenly shifts for Willie – the moment he steps outside, he is a dead man, and so he must constantly stay one step ahead of his hosts whose hands rest above their holsters. Just as Keaton delights in outsmarting the Canfield brothers, so too does he indulge in some darkly comic wordplay here, with the father making menacing small talk about the rainy weather – “It would be the death of anyone to go outside tonight” – and Virginia failing to recognise the irony of her piano piece, ‘We’ll Miss You When You’re Gone.’

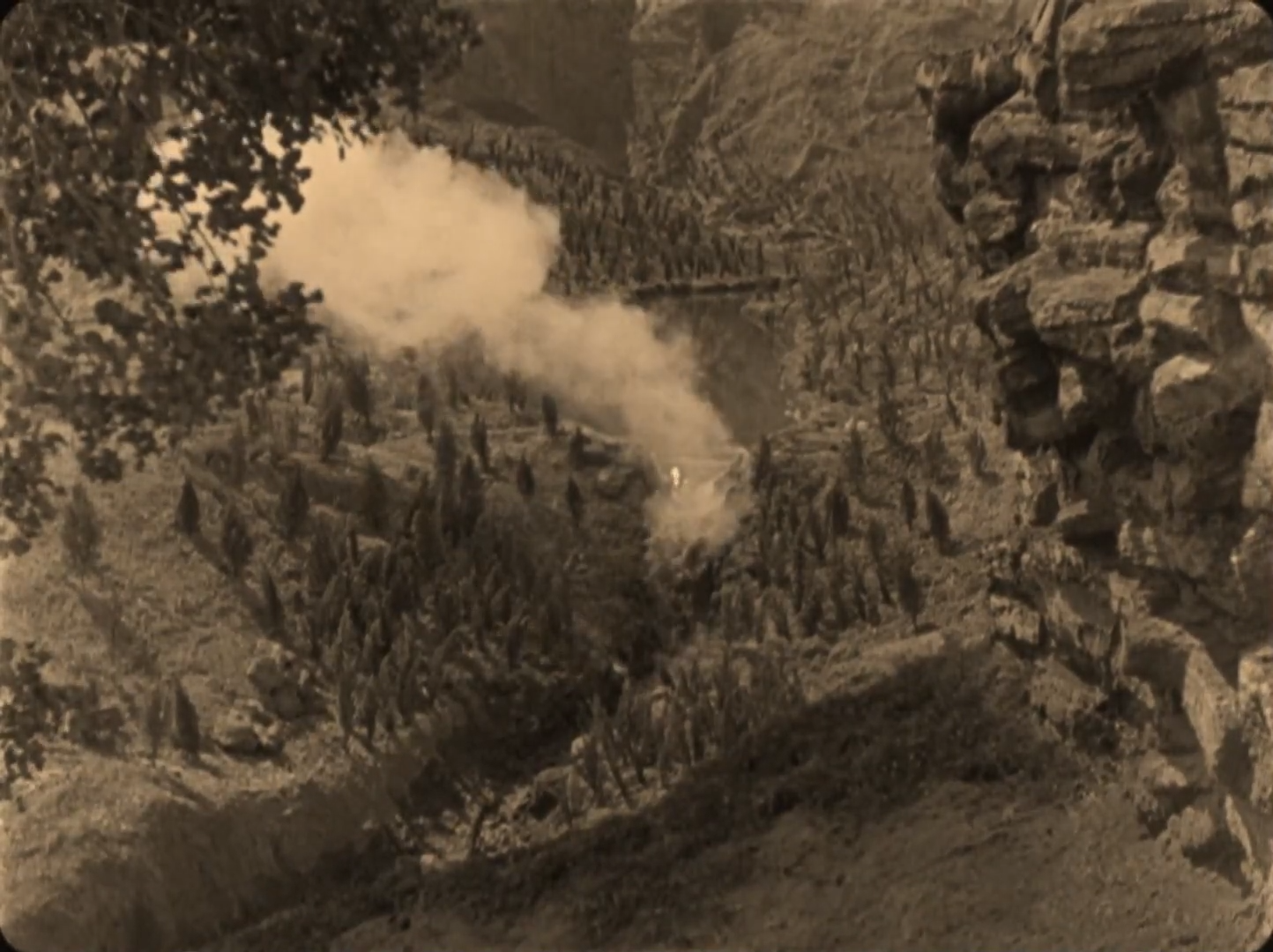

Still, Our Hospitality never strays too far from the real reason Keaton held such mass appeal to 1920s audiences, as right around the corner from every understated witticism is a grand set piece showing off his athletic stunt work. Much of the action here centres around a dam that is blown up early in the film to irrigate the surrounding forest, making for a superbly economical narrative when Willie is dumped from his getaway train into its waterfall. Steep drops such as these are where Keaton the actor works best, scaling cliff faces like a silent era Tom Cruise, throwing his full body into the action, and building up to one of the greatest stunts of his career. With a rope tied around his waist and Virginia being swept towards her death, he leaps from the edge of the cliff, grabs her by the arms, and saves her just as she begins her plummet to the rocky riverbed below.

Keaton’s physical presence may be violently pushed around by enormous forces far beyond his control, but it is his adept navigation of chaotic environments that makes him such a compelling figure to watch onscreen, and which further quells his conflict with the Canfields. Their truce does not just come through a laying down of arms, but a romantic union of children from two warring families like Romeo and Juliet – though of course Keaton does not squander the opportunity to play this as a brilliant final gag, giving up about a dozen guns revealed to be hidden on his body. Ignorance to immediate danger may be bliss in Our Hospitality, but accidentally ending a decades-old feud by saving a life may be even more gratifying.

Our Hospitality is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1910s & 1920s Decades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green