Park Chan-wook | 2hr 18min

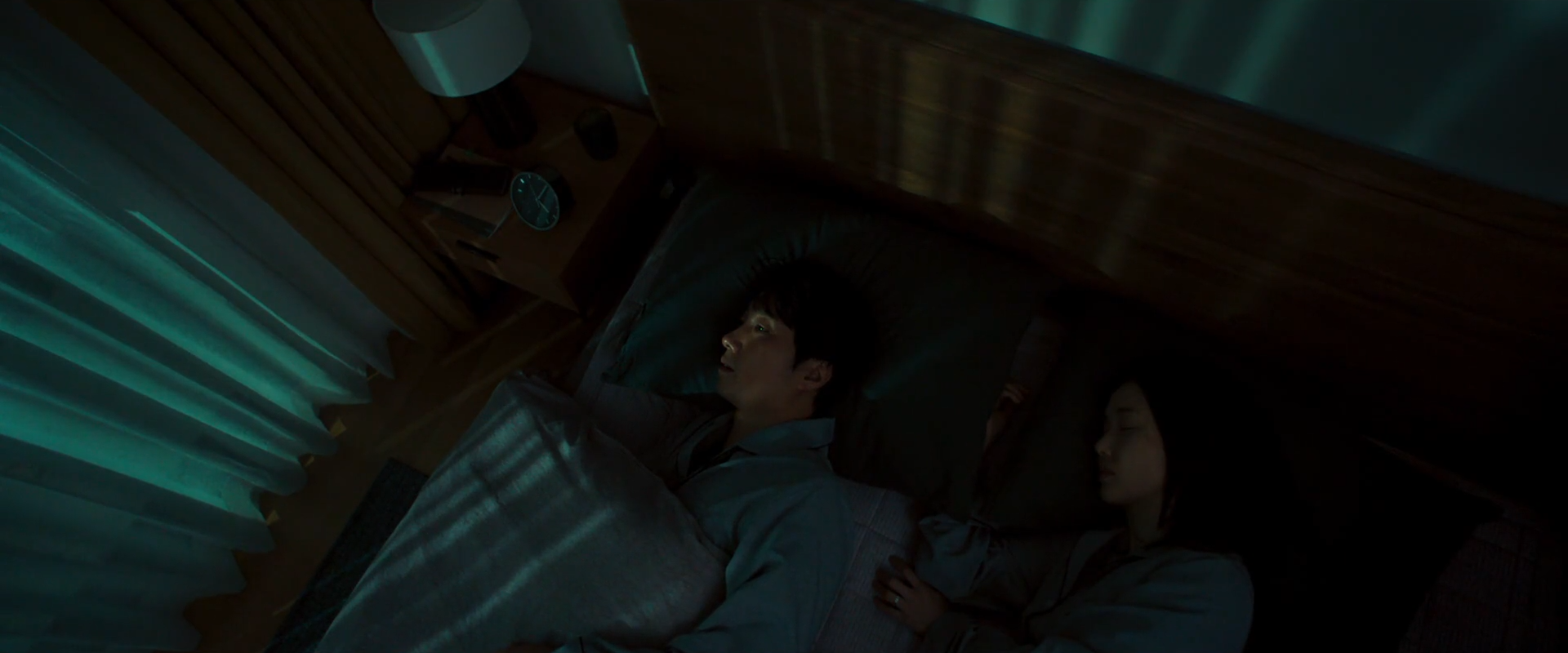

Detective Hae-jun does not let go of unsolved cases easily, instead sticking their photos up on the wall of the apartment he lives in during the week, and making them as much a part of himself as the marriage he returns to on weekends. This compartmentalisation is the only way he can properly function as a normal human being, and yet even his wife knows that drawing such a hard division between his home and work life is no perfect solution. As she observes early on, he grows morose when his routine becomes too peaceful. He is a man who needs murder and violence to be happy.

Given the fascinations of crime and vengeance running through Park Chan-wook’s career of brutally spell-binding thrillers, perhaps there is a little bit of himself written into Decision to Leave’s protagonist, much like the psychological obsession that Alfred Hitchcock shares with James Stewart’s detective in Vertigo. For Hae-jun, the subject of his psychological fixation is Seo-rae, a freshly widowed Chinese immigrant whose husband fell from a cliff while mountaineering. He spends hours questioning her with delight, sharing sushi and enjoying friendly conversation, though he does not let his guard down entirely. True to Park’s Hitchcockian sensibilities, a thread of surveillance is tied through this ambiguous relationship, visually navigating the boundaries and secrets that envelop it. Inside the interrogation room, Hae-jun and Seo-rae’s interview is set against a two-way mirror with split diopter lenses and focus pulls restlessly guiding our eyes between characters and their reflections, leading us to wonder whether he is really the only one here leading a double life.

The subjectivity of Park’s camera is virtually impossible to escape in Decision to Leave, taking the perspective of a dead man as an ant crawls over his eye, and tracing the subtlest character details in close-ups – the slight movement of a hand for instance, or the tan line left by an absent wedding ring. Park’s editing too adopts a fluidity in its graphic match cuts that, at their most graceful, delicately frame an anxious Hae-jun in the palm of Seo-rae’s hand through a long dissolve, and at their craftiest play tricks on our sense of space. Park will often rapidly shift back and forth between the detective and the distant subject of his focus in POV shots that keep cutting closer, before suddenly zooming out to reveal the drastically narrowed gap between them. All of a sudden, we find ourselves in Hae-jun’s mind where he is speaking to her directly rather than on the phone, and reconstructing a crime scene by invisibly stalking his visualisation of her.

In this voyeuristic compulsion there is something that goes beyond intellectual interest or romantic passion. Their relationship is defined by an unresolved longing, simultaneously drawing them together into the same intimate world, yet keeping them as far apart as the mountains and oceans woven throughout Park’s imagery. Quite significant to this is the language barrier that stands between them, situating Seo-rae as an outsider in Korea who needed her late husband’s influence as an immigration officer to keep her safe, and who occasionally uses a translator app to communicate complicated ideas. No doubt Hae-jun finds this an inconvenience at times, but at the same time it is yet another slight separation which he finds utterly tantalising in its precarious uncertainty.

Seo-rae is no passive subject of voyeurism in this equation though, equalling Hae-jun in shrewdness and recognising the mystery she perpetuates as the foundation of their relationship. Even as Park’s story spins off into concurrent cases that Hae-jun is investigating, it consistently winds back to Seo-rae as she helps him solve them, perhaps hoping to situate herself as his most impossible puzzle. So dedicated is she to this mission that when he finally gets to the bottom of her case and leaves, she encourages him to reopen it with newly incriminating evidence, desperately eager to rekindle their lost romance.

Even when it comes to Park’s costume design, his characters can never quite agree which side of his green and blue palette that Seo-rae’s teal dress lands on, letting her escape the binary that he paints with melancholic beauty all through his mise-en-scène. He lays it out with attention to detail in key props such as her green notebook, fentanyl pills, and beach bucket, but even on a larger scale too as he tracks Hae-jun’s chase across rooftops in one sweeping crane shot, he matches the urban scenery in the background to the same verdant colour scheme. His enthralling set pieces are perfectly suited to such gloomy yet tranquil designs, underscoring a subdued romance that finds gentle repose at a turquoise Buddhist temple, makes grisly discoveries in an empty swimming pool, and develops domestic bonds in Seo-rae’s apartment decorated with aquatic wallpaper.

At least, that is what the pattern resembles at first glance. On closer inspection, those waves could just as well be mountains, enveloped by a cool, chilly mist. Dizzying altitudes and deep bodies of water become fitting metaphors for this perilous connection, frequently threatening to send Hae-jun tumbling over the edge of steep drops not unlike Seo-rae’s deceased, rock-climbing husband. Her fear of heights is totally understandable when we reach the narrow, plateaued mountaintop where he perished, caught in a dizzying panorama as saturated in soft blue tones as the foggy sea she holds such fondness for. Hae-jun and Seo-rae may be united in the wistfulness of Park’s breathtaking colours, but symbolically they belong to entirely different worlds – him dangerously staggering atop treacherous summits, and her dwelling in the mysterious, oceanic abyss, pulling lovers down to her level and sending damning evidence into its depths.

The danger in this romantic tension does not come from any malice on Seo-rae’s part, as she herself recognises the sacrifices that Hae-jun makes in protecting her, but rather the inherent incongruency of their stations in life. He is a police detective, destined to observe and contemplate crime from a distance, but never to cross that line to the other side. Seo-rae, recognising how much these boundaries define their love, cannot stand to see them broken. Not only would her guilt compromise his innocence, but once he sees her as she is, she would also become just another solved case taken down from his wall and ultimately forgotten.

There are so many shots in Decision to Leave that leave us teetering on the edge of mountains and rooftops, it is somewhat surprising to find the most impactful tragedy of the film takes place on a cold, lonely beach. That this is where Seo-rae decisively resolves to “unsolve” Hae-jun’s case is poignantly poetic in its open-endedness, sinking her into an oceanic enigma that he may very well spend the rest of his life trying to unravel. For lovers as deeply obsessive yet incompatible as these, such elusive romance can only be kept alive through death, bound together by the promise of an eternal, impenetrable mystery.

Decision to Leave is currently streaming on SBS On Demand, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2022 – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2020s Decade (so far) – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2022 in Cinema – Scene by Green