Warren Beatty | 3hr 20min

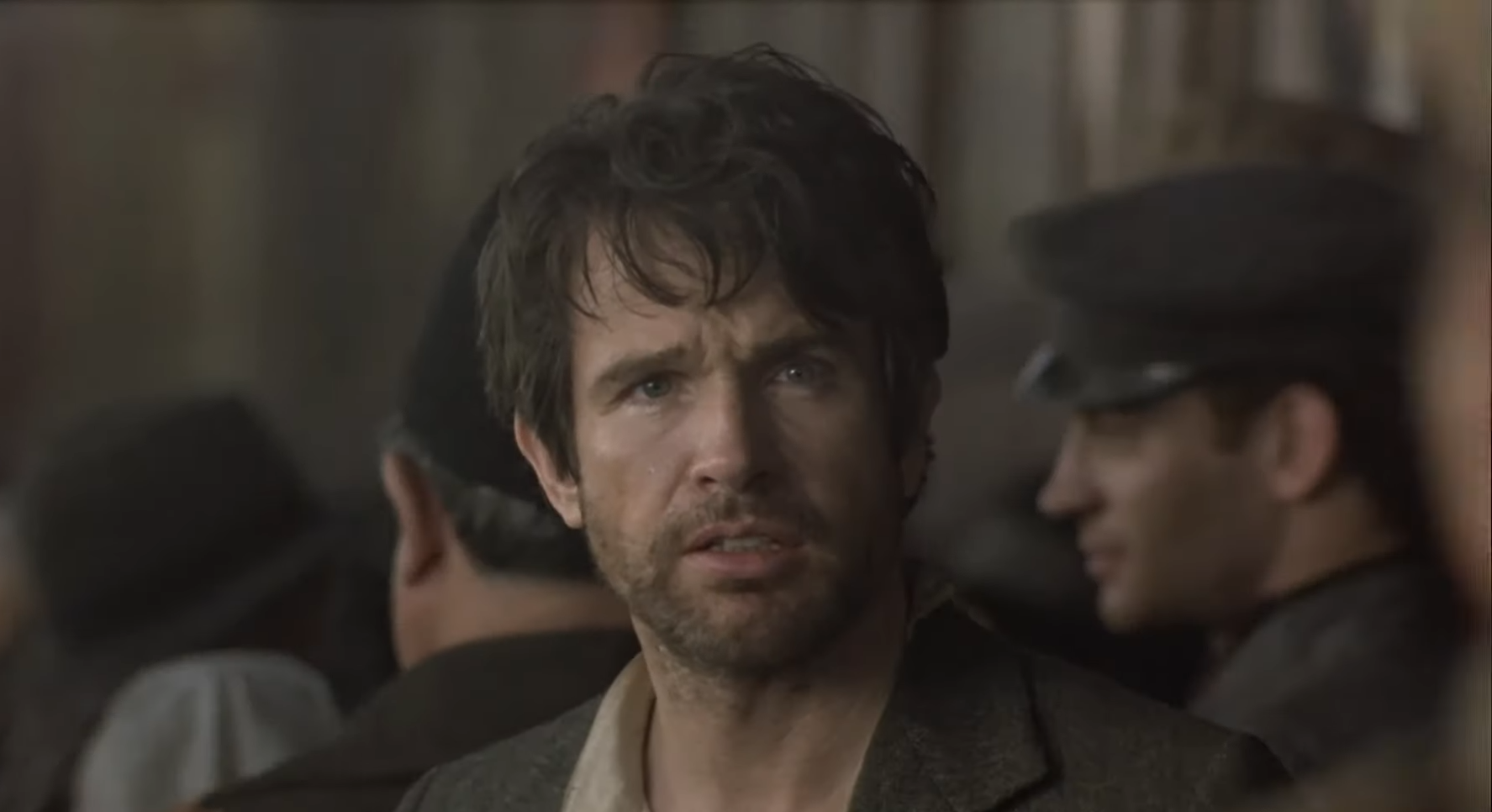

History buffs will recognise the name John Reed as that of the American journalist who travelled to Russia in 1917, wrote the most vivid firsthand account of its revolution, and published his observations in the book ‘Ten Days That Shook the World’, drawing acclaim and criticism from across the political aisle. If his Communist leanings manifested with full-throttled admiration in his descriptions of the new society as “a kingdom more bright than any heaven had to offer,” then Warren Beatty symbolically ties him even closer to the movement in Reds. It is an archetypal rise and fall narrative he follows, but one which is romantically mirrored across three separate layers in the evolution of early twentieth century socialism, Reed’s own political activism, and his love for fellow writer Louise Bryant. In this bright-eyed, intellectual man we find the living embodiment of a 1910s American counterculture, confidently promising a hopeful future of equality doomed to fall to bureaucracy.

Besides the epic storytelling structure, the other key to unlocking the brilliant form of Reds is in the interviews Beatty conducts with ‘witnesses’ who knew Reed personally, tempering his subject’s impassioned fervour with nostalgic reflections. With their faces framed off to the right against black backgrounds, these men and women offer an authenticity which distinguishes Beatty’s film from so many other historical epics.

As such, Reds practically verges on docudrama territory, bridging the gap between fiction and reality through formal rhythms that pulse with humour and sensitivity. Right after one woman fondly recalls the days when homosexuality and abortion were taboo, Beatty irreverently cuts straight to a man testifying that there was just as much sex going on then as there is now, playing to the amusing incongruency between personal accounts that keep us from forming an objective picture of the past. With such faultless historicity rendered impossible though, these different perspectives also make up a more complex view of our primary subject, Reed. As one witness states, “A guy who’s interested in changing the world either has no problems of his own, or refuses to face them.”

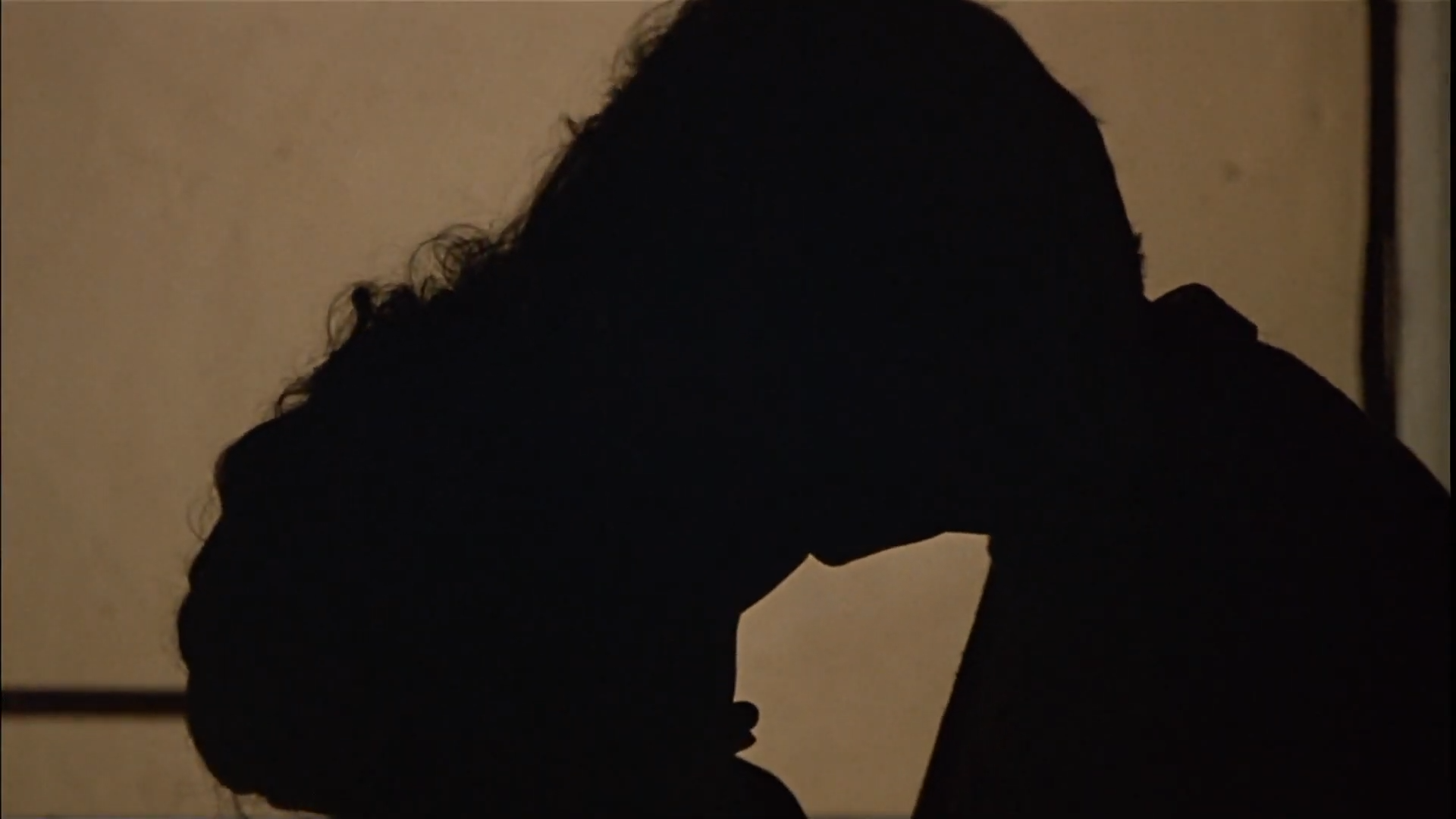

Beatty’s Greek chorus-style interludes are seamless, at times simply manifesting as voiceovers commenting on events while we are whisked from New York City’s bohemian Greenwich Village to the stunning white beaches of Provincetown, and further onto the frontlines of the Russian Revolution in Petrograd. The narrative scope is sprawling, and both he and his co-star Diane Keaton wear every bit of it in their performances, ageing Reed and Bryant from hopeful young radicals into disenchanted cynics.

For Keaton especially, this is an acting achievement that sits among her best, setting the screen on fire with feminist monologues lamenting how much society ties her success to her husband, and later proving her tenacious, unconditional love as she hikes through Northern Europe’s frozen wilderness to rescue him from prison. With Jack Nicholson, Gene Hackman, and Paul Sorvino confidently filling in supporting roles too, Reds stands as a testament to the power of excellent casting, representing significant historical figures with big names of 80s cinema.

Beatty does not stop there in his collaborative ambition either, pulling Vittorio Storaro onboard as cinematographer to instil his grand biopic with an antiquated, painterly quality. The period detail in his establishing shots of New York’s streets and the sweeping crane shots over Bolshevik crowds effectively establish the grand spectacle of Reds, but even more substantial is Reed’s association with them, manifesting the full scale of his political aspirations spanning entire nations. When the Czarist White Army attacks his train, he boldly runs right into the clouds of dust and smoke, while at a large Communist rally he steps up onstage to assure them of America’s favourable support. It could be the fact that he is once again working closely with Bryant, or perhaps it is the exhilaration of seeing history unfold around them, but the romance between both is also rekindled during their time in Petrograd, holistically revitalising his spirit with the fiery zeal of the Russian Revolution.

The novelty of such grand passion can only last so long though before its shine begins to dull and complications surface. The irony of Reed’s frustration with Russia’s new, inflexible governance isn’t lost on Beatty who correspondingly explores the journalist’s own fracturing socialist regime back in the United States, as his Communist Labor Party of America splinters off from the more centre-left Social Party of America. Reed’s efforts to have his new party officially recognised by Russian authorities are in vain – not only does Bryant threaten to end their relationship should he venture across the world for a second time in stubborn pursuit of validation, but the Bolsheviks reject his proposal anyway, and bluntly refuse to assist his illegal crossing of borders to return home. To Reed, Russia’s militaristic police state that spawned from a freedom-seeking movement has destroyed any hope of real communism, and in a single foolish decision, he effectively severs his ties to his homeland, his party, and his wife.

If there is any solace to be found at the end of Reds, then it is in that tenacious love he shares with the latter, sending Bryant across frozen wastelands and Reed through hostile territory to finally end up in each other’s arms. They look rough around the edges, but their eyes are also softer than ever, for the first time recognising the inimitable bond they share beyond the intellectual joys and constraints of their political interests. It is a reunion that comes far too late for their romance though. With Reed’s passing from typhus less than a month later, Beatty virtually canonises him as a saint of lost causes, illuminating his body in a white light through a narrow hospital doorway as Bryant’s silhouette kneels in grief by his bed. In this final shot, the death knell of American socialism is finally tolled, and Beatty signals the end of an era destined to live on in the wistful memories of Reds’ venerable witnesses.

Reds is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green