Christopher Nolan | 3hr

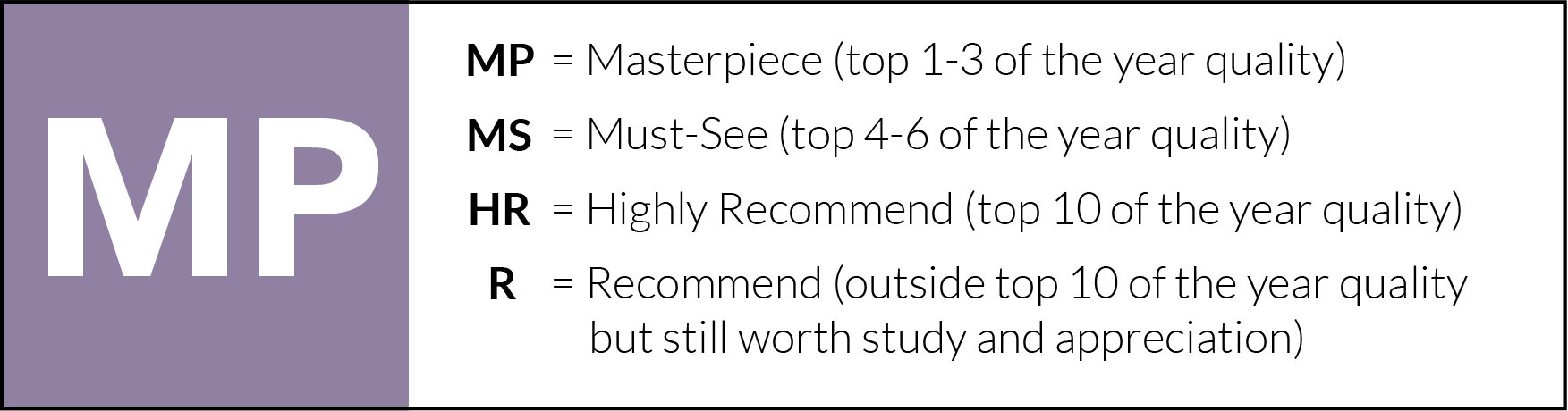

The inklings of an earth-shaking idea are born in J. Robert Oppenheimer’s mind as a university student, and sparks begin to ignite. Beams of electricity arc out across darkness, bursts of flame dissolve into smoke, and rings of light excitedly vibrate. Physical reactions such as these are born from the ideas of great men, setting off a chain reaction that advances human civilisation one innovation at a time. It is also evident in Oppenheimer though that the excitement of manipulating raw matter is enough to cloud even the most intelligent physicist’s judgement. As the father of the atomic bomb is straddled mid-coitus by his mistress, psychiatrist Jean Tatlock, she asks him to translate a passage from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita she is holding, and all at once Christopher Nolan links the act of life-giving creation to humanity’s eventual destruction.

“Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

In Western culture, these words spoken by Krishna have since become more heavily associated with Oppenheimer, framing him as a god carrying the burden of seemingly infinite power. Indeed, the atomic blast which can level entire cities proves to be “a terrible revelation of divine power,” forcing those who wish to gaze upon its radiant brilliance to shield their eyes from its wonder and horror. It is a sight not easily forgotten, continuing to haunt Oppenheimer in visions as psychologically invasive as those brief flashes of kinetic energy we witness early on. If Terrence Malick’s elegant interludes in The Tree of Life marvel at the expansive cosmos of the universe, then Nolan’s are in total awe of its quantum processes, and the largescale devastation they produce.

Oppenheimer is only Nolan’s second excursion into the annals of history, and it may very well be his densest narrative yet. Still, there is no doubt to be had that this bleak biopic fits perfectly into his career of thrillers and science-fiction films. True to his formal fascinations, time distorts around his central character in non-linear configurations, all the while grounding his story in parallel timelines neatly labelled “Fission” and “Fusion.”

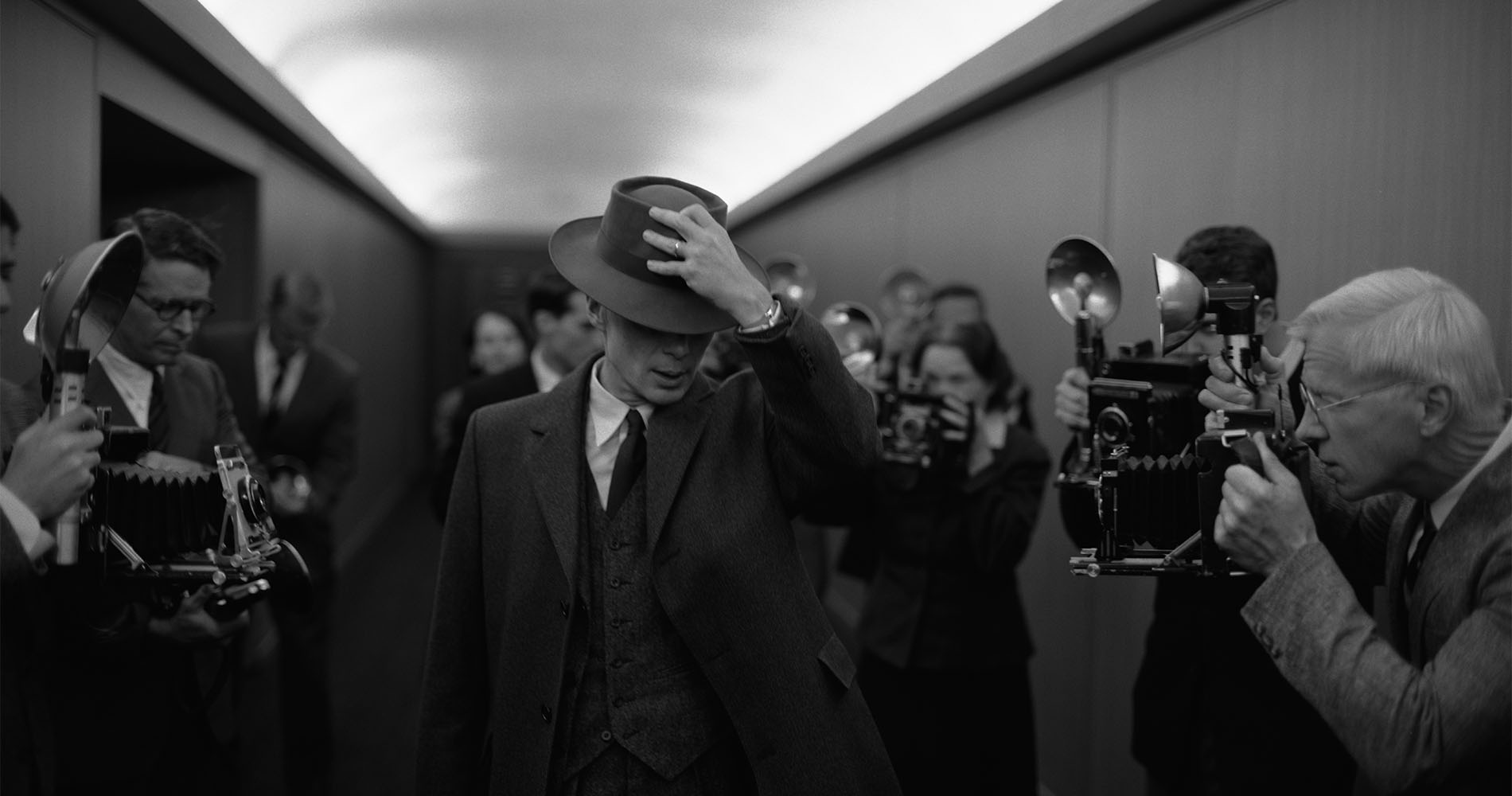

Fission is the nuclear reaction central to the atomic bomb, splitting a nucleus to wreak enormous havoc and giving its name to the 1954 security hearing subplot, where we follow the government’s efforts to frame Oppenheimer as a Communist and strip him of his clearance. Meanwhile, fusion is the merging of two nuclei into one, crucial to the far more powerful hydrogen bomb supported by Washington bureaucrat Lewis Strauss, who dictates much of the second timeline at his 1959 confirmation hearing for the Senate.

Both framing devices present alternate perspectives of Oppenheimer’s rise from his studies at Cambridge to leading the top-secret Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, though Nolan also visually distinguishes between them by presenting Strauss’ story in black-and-white. How the two connect remains somewhat of a mystery for much of the film, and yet as the final act arrives, Nolan skilfully fuses them with great formal precision.

To pull off such an immense feat of narrative structure though requires an equal achievement of editing, posing a challenge that Nolan has demonstrated himself more than capable of handling in the past. Jennifer Lame has now seemingly taken over from Lee Smith as Nolan’s regular editor, following up her astounding work on Tenet to craft what is essentially a 3-hour montage of increasing urgency, not unlike Oliver Stone’s political thriller JFK. Huge levels of stamina are required on Lame’s part to keep this momentum up for such long stretches of time, as she bounces multiple timelines off each other in her propulsive parallel editing, and intermittently cuts away to those tiny surges of pure quantum energy representing Oppenheimer’s inner thoughts.

The pounding electronic score composed by Ludwig Göransson plays a crucial part in maintaining this kineticism as well, barely pausing long enough to allow us any breathing space in our rush towards total annihilation. At the same time though, Nolan is wise in his selection of those sequences where he drops it out altogether, forcing us to linger in the uncomfortable, heavy breathing of those bearing witness to the product of Oppenheimer’s life’s work. As we sit in the incredible majesty of this climactic moment, it isn’t hard to see the existential allure that drew him into this project. Nolan’s rejection of CGI and commitment to practical effects pays off on a grand scale in Oppenheimer’s disturbing nightmares of a nuclear apocalypse, but it is most of all in his lifelike simulation of the Trinity test that we feel his historical impact on a painful, visceral level.

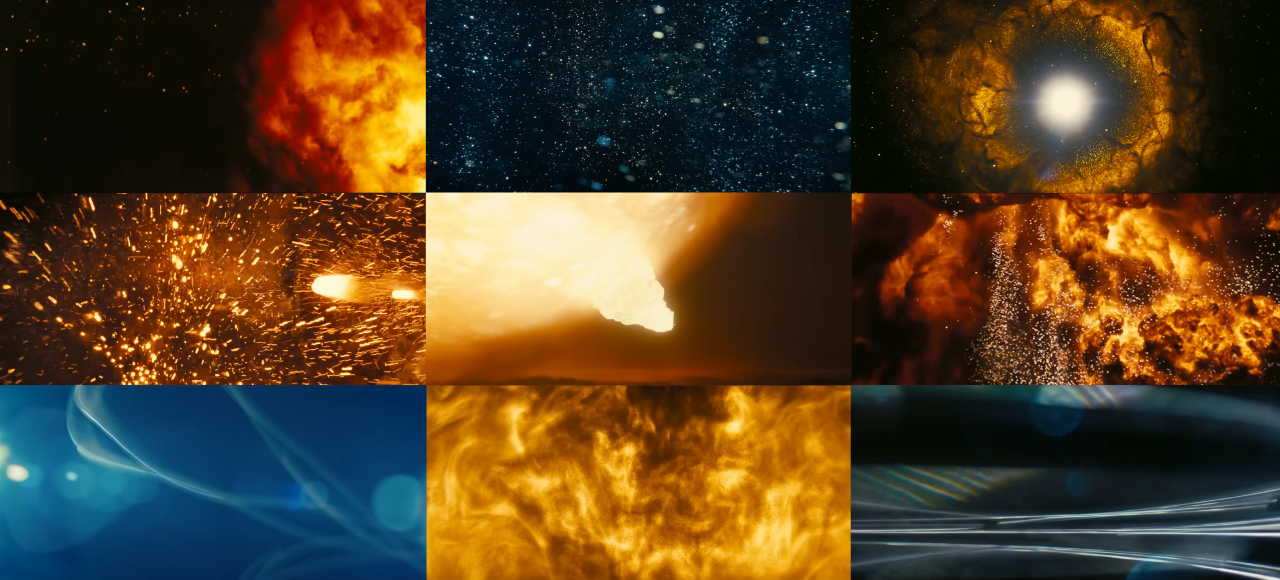

There are few cinematographers who have capitalised so well on modern IMAX technology as Hoyte van Hoytema over the past decade or so, and so of course credit must also be given to him for both the sheer spectacle of these set pieces and the tremendous establishing shots of Los Alamos. Few times before have we additionally seen this largescale format applied to close-ups as intensive as those captured here, staring right into Cillian Murphy’s glassy blue eyes stretched wide open with the guilt of knowing what he has done, and what he is about to do. It is often thanks to this framing that we can truly appreciate his studied performance as Oppenheimer, adopting the physicist’s deep voice and clipped intonations in his speech, and ageing from an idealistic student into a middle-aged man stalked by regret.

If Heath Ledger offers the best performance of any Nolan film in The Dark Knight, then Murphy surely sits at a very close second. The rapturous applause that his fellow Americans greet him with after his bomb ends the war rings silently in his ears, and rooms seem to vibrate with atomic vibrations around him, radiating his psychological disintegration out from his haunted expressions into his environment.

Oppenheimer may be Murphy’s platform to give one of the best leading performances in recent years, but it also proves to be a showcase for a whole ensemble of A-list actors making the most of their time in the spotlight, including Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Florence Pugh, Benny Sadie, Rami Malek, and Kenneth Branagh. After Murphy though, there is only one actor whose presence leaves a near-equal imprint on the film. Robert Downey Jr. has never been better than he is here as Strauss, Oppenheimer’s friend-turned-rival who becomes vindictively caught up in his own petty grievances. The final act is where he truly flourishes in his vicious spitefulness, cruelly plotting against the physicist and picking at his open wounds like a vulture. It is through his character development that the second line of the film’s opening quote is prophetically fulfilled, simultaneously immortalising Oppenheimer as a mythological figure, and dooming him to suffer at the hands of his guilty conscience and political enemies.

“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.”

There may be no bleaker ending of any Nolan film than that which he delivers here, simultaneously turning back the clock to take an alternate perspective of a scene from earlier in the film, and looking ahead to the future that awaits us. If Dr. Strangelove presents a darkly comic take on humanity’s nuclear self-destruction, then Oppenheimer is its evil twin, leaving us shivering with existential terror. Just as the tiniest of quantum processes may produce vast, explosive reactions, so too can one man set off seismic ripples across human history. From his creation springs death, and under his shadow Nolan whisks us forward with a relentless pace to witness the tortured god that emerges out the other end – the immortal Destroyer of Worlds.

Oppenheimer is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2020s Decade (so far) – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Where do you think it would land up on your best films of all time? And what do you think is better between this and Dunkirk?

I wouldn’t want to commit to anything this early on, but I think somewhere in the 100-200 range. I still believe Dunkirk is the greater achievement. In a few years it will be eligible for my all-time list, and it could land between 50-100.

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Editors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Cinematographers of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Composers of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green