Greta Gerwig | 1hr 54min

If Barbieland is a bright pink reinterpretation the Garden of Eden, with Barbie and Ken as the Adam and Eve figures opening the door to corruption, then where in Greta Gerwig’s piece of cinematic confectionary do we find the snake who introduces it to them? Perhaps applying biblical metaphors to Barbie is a little kind – this is not a film that asks for audiences to uncover any rich symbolism or subtext, even while it is playing on narrative archetypes set by some of humanity’s oldest stories. Quite unusually for both Gerwig and her cowriter Noah Baumbach, this screenplay would much rather plainly state its message in unambiguous feminist slogans that were expressed with far greater finesse in Lady Bird and Little Women. Still, she is keenly aware of what she is setting out to achieve, even if the artistic stakes are a little lower and the popular appeal is broader than her previous films. Armed with self-aware humour and a kitschy production design, Barbie makes for a dazzling treat, balancing its satirical interrogation of the doll’s controversial place in pop culture against the innocent joy of everything it was intended to represent.

As for where the tension arises between those two contradictory notions, then we must consider that aforementioned source of corruption in Barbie – not any external force bearing malicious intent, but rather those innate flaws which we can only excise through idealised, plastic representations of ourselves. They set the empowering standard that the originators of the Barbie doll believed women should aspire to, encouraging them to become doctors, lawyers, and writers who may never be subservient to their Kens, and yet there is also a lack of nuance in this ideological thinking which Gerwig is sharply critical towards. Sixty years on from Barbie’s invention, she has become an icon of “sexualised capitalism”, rejected by girls looking for more relatability in their role models. Therein lies the existential crisis that Barbie faces when she ventures into the real world.

It is hard to imagine a pair of actors better suited to playing Barbie and Ken than those that Gerwig casts here. Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling pose, strut, and roller skate their way through the film with magnetic charm and humour, individually set on opposing visions of utopia that bring them into conflict over what this exactly means for their respective genders. There may be some comedy which misses the mark in this film, but never when it is in either of their hands, and least of all when Gosling steals the show with his 80s pop musical number ‘I’m Just Ken’.

Even beyond its high-energy dance-offs and broad slapstick though, Gerwig embraces the camp theatricality of Barbie’s pop culture status right down to its dollhouse aesthetic, cartoonishly painted across an entire city. It is fortunate that we don’t spend too long following Barbie’s journey through the real world given how much of this film’s strengths lie in the absurdly garish design of Barbieland, setting the scene for an amusing battle of the sexes across pastel-coloured beaches and streets.

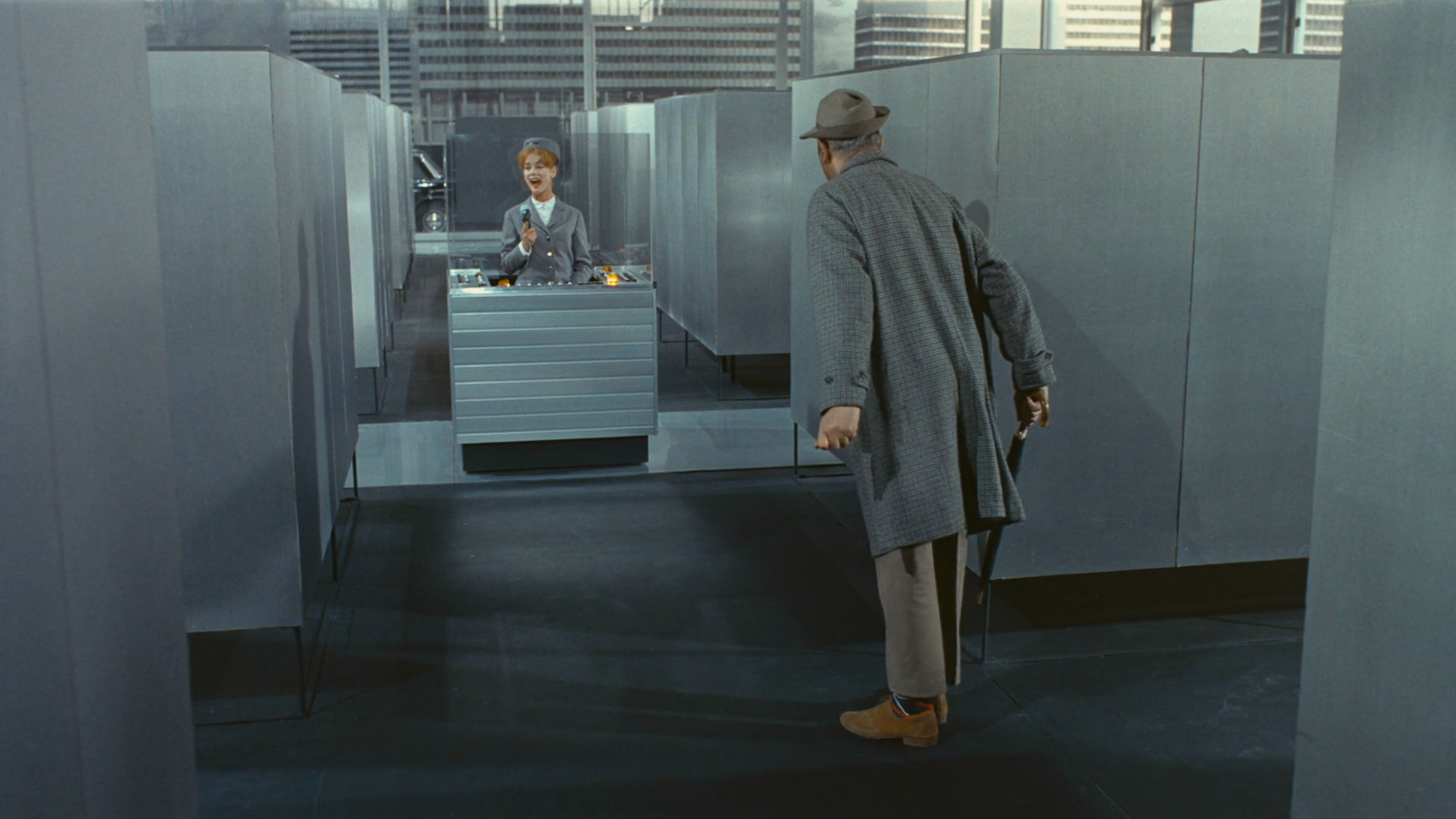

From the make-believe water running out of faucets to the open-air dreamhouses that disregard walls altogether, Gerwig accomplishes a beautifully curated feat of world building here, especially drawing inspiration from the artificial city that Jacques Tati built for his 1967 French satire Playtime. Even closer comparisons can be drawn when we reach the Mattel headquarters, with our similarly naïve protagonist striding down endless rows of grey, boxy cubicles to the heart of the bureaucracy that controls her image. This set piece in its entirety is wonderfully inventive, sending Barbie up to the top floor where Will Ferrell’s ditzy CEO meets with other executives, before plunging her to its basement where the company’s ghosts live on. At the same time though, it is also indicative of a larger trend in the film that lets its smaller subplots and formal threads quietly fizzle out, including the careless disappearance of Helen Mirren’s narration by the end.

Even so, there isn’t a second of Gerwig’s film that isn’t entirely dedicated to the love and appreciation of its central icon, revealing the depths of Barbie lore that no one besides a very niche group of fans might have suspected existed. One of the great running jokes comes in the homages to those bizarre, discontinued dolls that never quite fit the mould, yet even they find renewed purpose here as misfits whose mere existences expose the hidden prejudice of Barbieland’s rigorously high standards. The existential discomfort of being human is a small price to pay for the freedom that comes with choosing one’s own identity, and Barbie goes even further to revel in the delightful incongruency of that awkwardness against such overcooked perfection. The matriarchal paradise that Gerwig builds with careful curation and whimsy in Barbie is not a utopia to be protected from humanity’s flaws, but a dreamy vision that sees both come together in perfect, feminist union.

Barbie is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green