Park Chan-wook | 1hr 55min

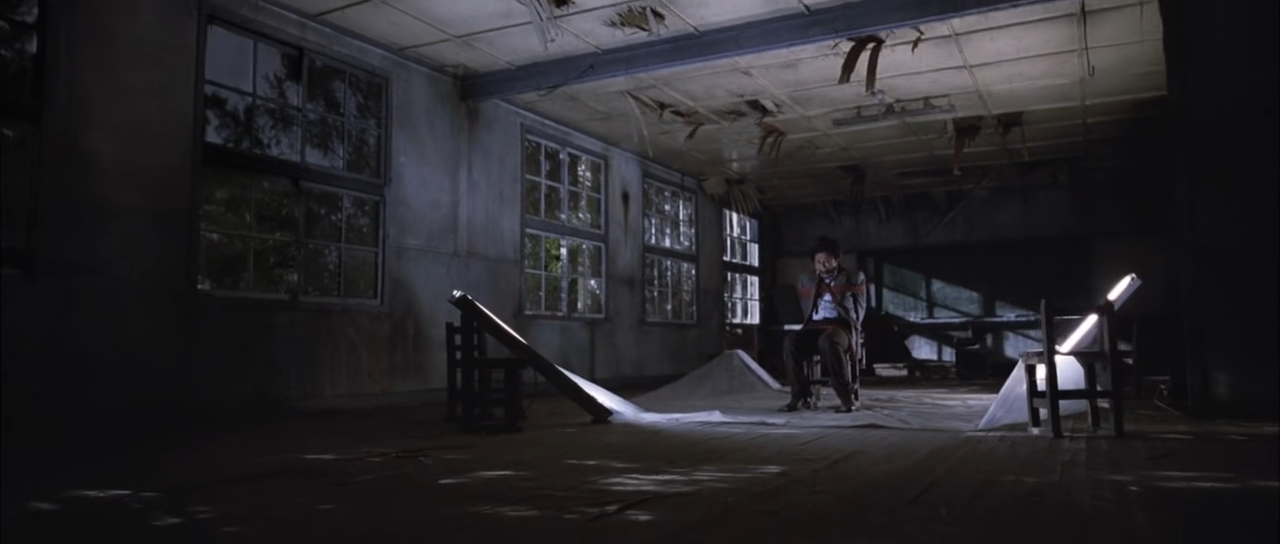

The loss of innocence is no small tragedy in the final instalment of Park Chan-wook’s thematic Vengeance trilogy. Whether it is eroded over time as it is for ex-convict Lee Geum-ja, or instantly annihilated as we see in her old mentor’s sadistic murders of children, its erasure is a permanent fixture that no amount of retribution can restore. Equally though, the alternative of letting those who have perpetuated such soul-destroying misery go unpunished offers no real resolution either, denying any sort of catharsis to their victims. Geum-ja has many complex reasons driving her mission to track down serial kidnapper and killer Mr. Baek, but buried deep within all of them is a corrosive melancholia, represented here not through the cool, passive hues of so many other Park films, but rather by burning crimsons that stain her journey with raw, wounded anger.

Park’s formal dedication to setting these blood red tones against clean whites in his mise-en-scene emphasises this severity even further, greeting Geum-ja with its shocking visual contrast when she is granted an early prison release. Outside those concrete walls, a group of Christian church singers dressed in Santa outfits offer her a block of tofu, traditionally symbolic of one’s redemptive decision to become pure like the snow that falls lightly on their shoulders. Her cold rejection of their proposed salvation brusquely indicates the path she has chosen. She is not looking to restore her long-lost innocence, but to turn her cruelty against the man who taught it to her, applying a striking red eyeshadow to her face as she takes on the mantle that she has spent thirteen years in prison crafting – Lady Vengeance.

As dogged as Geum-ja is in her furious efforts to hunt down Mr. Baek, there is also an elegant restraint to her navigation of such personal traumas, captured in Lee Young-ae’s sublimely balanced performance that sits somewhere between angelic and diabolic. So too does it extend to Choi Seung-hyun’s baroque score of strings and harpsichord, relentlessly pulsing along to steady, staccato rhythms that only barely hide a muted fury and sorrow.

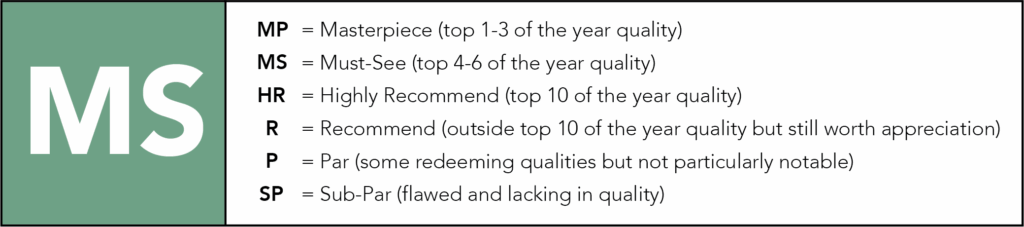

For a long time, the source of this anguish seems mysteriously distant, as Park chooses to hide the face of the man responsible like a painfully repressed memory. Through his narrative of tightly interwoven flashbacks, it often feels as if we are seeking some reason behind his cruelty and exploitation, especially given how effortlessly it hides behind shallow displays of kindness. When Geum-ja falls pregnant at the age of 20, Mr. Baek is the first person she goes to for support, falling so much under his spell that she readily supports his kidnapping racket and takes the fall for his ‘accidental’ killing of a young boy. Within this morbid plot lies an even darker truth though – this teacher specifically targets children at the schools he works at, satiating his sadistic hatred through torture and murder. Even before we meet him directly, Mr. Baek is thoroughly built up as one of Park’s most monstrous characters, so when he is revealed as a dumpy, bespectacled man, Lady Vengeance forces us into a chilling recognition of evil’s unassuming façade.

If such burning hatred exists within a man as seemingly gentle as Mr. Baek, then it stands to reason that his groomed pupil is equally capable of extraordinary violence despite her youthful beauty. It is a perversion of everything we are led to believe about good and evil, even inciting a media storm that cannot reconcile the two extremes in a single person when she initially confesses to Mr. Baek’s crimes. Even beyond this dichotomy drawn through Park’s red-and-white colour palette, it also manifests in the formal relation between his grotesque subject matter and the stylish grace with which he navigates it, fluidly transitioning into flashbacks with graphic match cuts and floating the camera through scenes of brutal torture. Geum-ja cannot be solely defined by either her purity or retributive anger, but much like an avenging angel sent to deliver uncompromising, righteous justice, she is an indivisible composite of both.

It is not just the thirteen years lost in prison while her daughter Jenny was growing up that she mourns, but the guilt of knowing she is responsible for her abandonment issues plagues her as well. It takes a huge amount of humility then on her part to realise that despite all this, her suffering may be the least of all Mr. Baek’s surviving victims. While she can at least accept some responsibility for it, the parents of the children he killed spend every day wrestling with the incomprehensibility and randomness of their tragedy. This revenge mission belongs not just to her, but to a whole community of mothers and fathers, now being given the ultimate decision of how to deal with the monster of their nightmares.

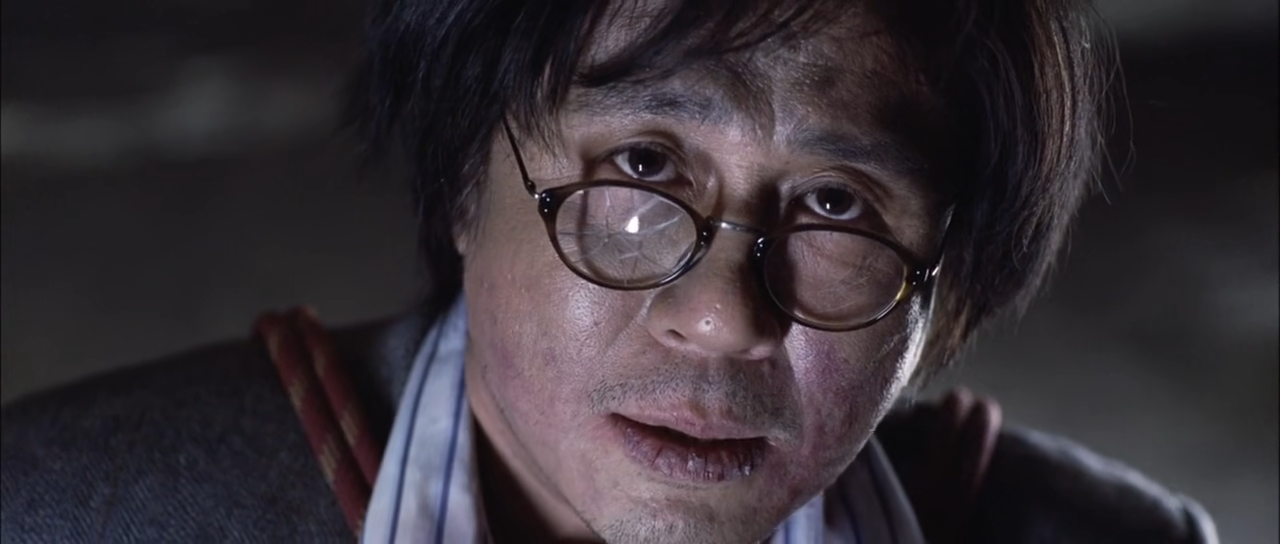

What are any of them to take from this violent reprisal though? Going off Park’s previous film Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, one might almost expect their bloodthirst to be judged with more scepticism that they are solving anything at all by perpetuating further suffering. He doesn’t entirely reject that idea here, but there is at least some therapeutic salvation in these characters deliberating the futility of their actions – no amount of vigilante justice will ever return their children. Still, they line up outside the classroom that Geum-ja has tied Mr. Baek up inside all the same, taking turns to inflict physical representations of their emotional agony on him, and confront the pitiful mortality of its source. Evil is not some invisible, demonic force, they discover, but entirely human, as regrettably intrinsic to our being as the innocence it destroys.

Then again, perhaps there is also the potential for it to serve a more protective purpose as well. Only when Geum-ja’s innocence is gone does she appreciate its real value, and further seek to preserve it in her daughter before the psychological damage she has done becomes irreversible. As she stands with Jenny on a snowy street, she is once again gifted the symbolic tofu in the form of a white cake, offering a purification of her soul. This time, she does not brush it off, but given the heaviness of her sins, neither can she accept it. Instead, all she can do is bury her face in its soft layers, longing for the redemption that her vindictive mission has failed to deliver, despite it playing out exactly as she intended. For Geum-ja, there is no total victory in the battle between purity and corruption. Just a prolonged battle to protect one by vengefully enacting the other.

Lady Vengeance is not currently streaming in Australia.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2000s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green