Ingmar Bergman | 6 episodes (41 – 52min) or 2hr 47min (theatrical cut)

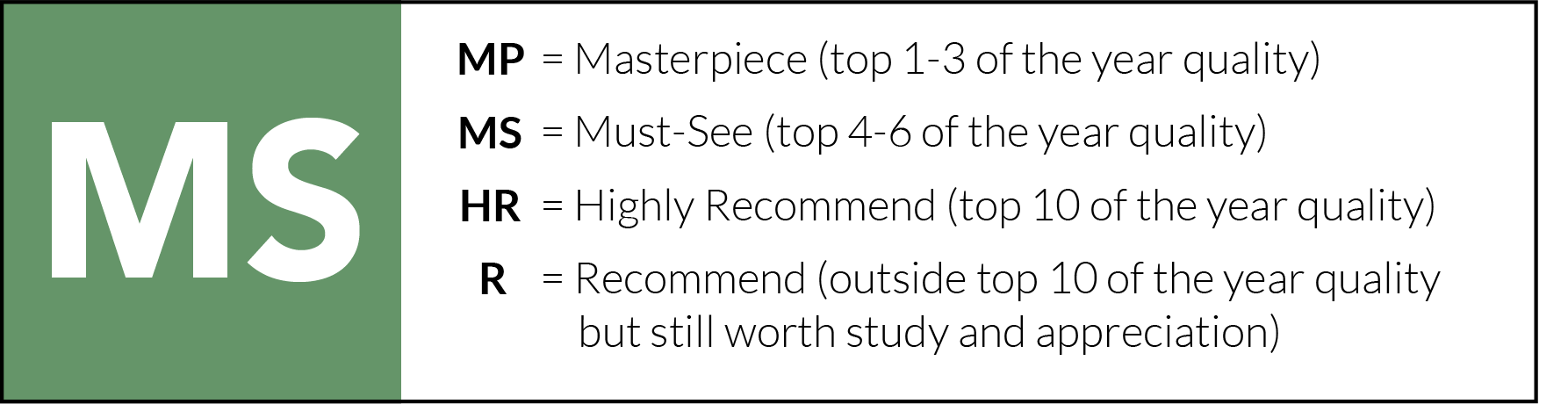

True to its title, Scenes From a Marriage never sways from its tight focus on six isolated episodes of Johan and Marianne’s married life, using each to piece together a collage of a fragmenting relationship across ten years. The couple often speaks of other people who are important to them, including their unseen children and extramarital lovers, yet the only characters who ever take up a substantial amount of screen time are those who act as counterpoints to them. In one scene we watch Marianne’s mother reflect on how disconnected she felt from her late husband, while at a dinner party two married friends, Katarina and Peter, pour out a verbal stream of visceral disgust at each other.

“I find you utterly repulsive. In a physical sense, I mean. I could buy a lay from anyone just to wash you out of my genitals.”

At first, Johan and Marianne might seem like the most ideal couple of them all, and their friends even acknowledge this when considering the awkward situation that has arisen from their unbarred scorn. “It will do their souls good to catch a glimpse of the depths of hell,” they joke, but perhaps that glimpse was more of a stimulus than they realise.

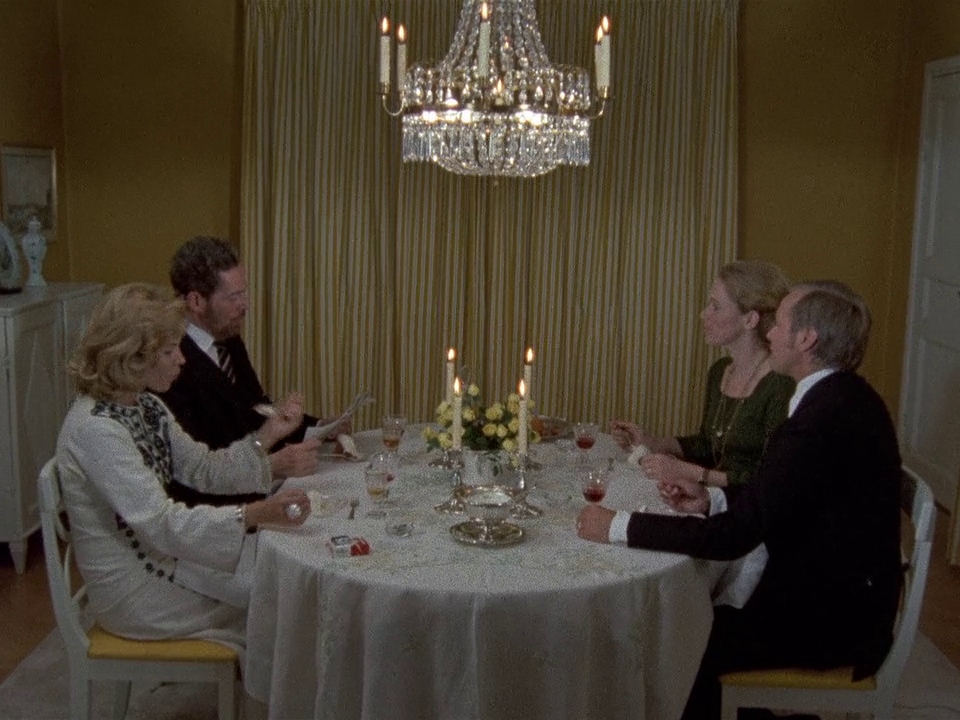

When we first meet Johan and Marianne, they are pushing the false image of their unwavering love in a magazine interview, speaking about the ten years they have been wed. Conversation unfolds organically in Ingmar Bergman’s dialogue, painting a portrait of Marianne as a woman who is no stranger to separation. Not only has she ended a marriage once before, but she continues to see clients undergo the same experience in her profession as a divorce lawyer. Perhaps it is because she is so familiar with others’ problems, or maybe she just possesses a deep-rooted desire for stability, but clearly she has considered the subject from every angle save for a personal one. In this interview, the illusion of her marital contentment is only ever broken in the journalist’s uncomfortable interruptions, as she constantly arranges them into poses for the camera which expose the artifice behind it all.

Ingmar Bergman’s writing is some of the strongest it has ever been here, dispensing with his usual traces of surrealism for a realism that confronts the awkward complexities of his characters head-on. In doing so, he is also creating his most forthright examination yet of bitter conflicts that divide once-passionate lovers, in slight contrast to almost every other film of his over the past decades which have lingered such interrogations on the edges of other more faith-based questions.

Also quite unusual for Bergman is his move to a television format, simultaneously serving the extended, episodic structure of his story, yet unfortunately compromising on his usually impeccable visual style. Even with his regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist at hand, the tiny budget that the network gave them does not allow for the sort of lush production design of Cries and Whispers.

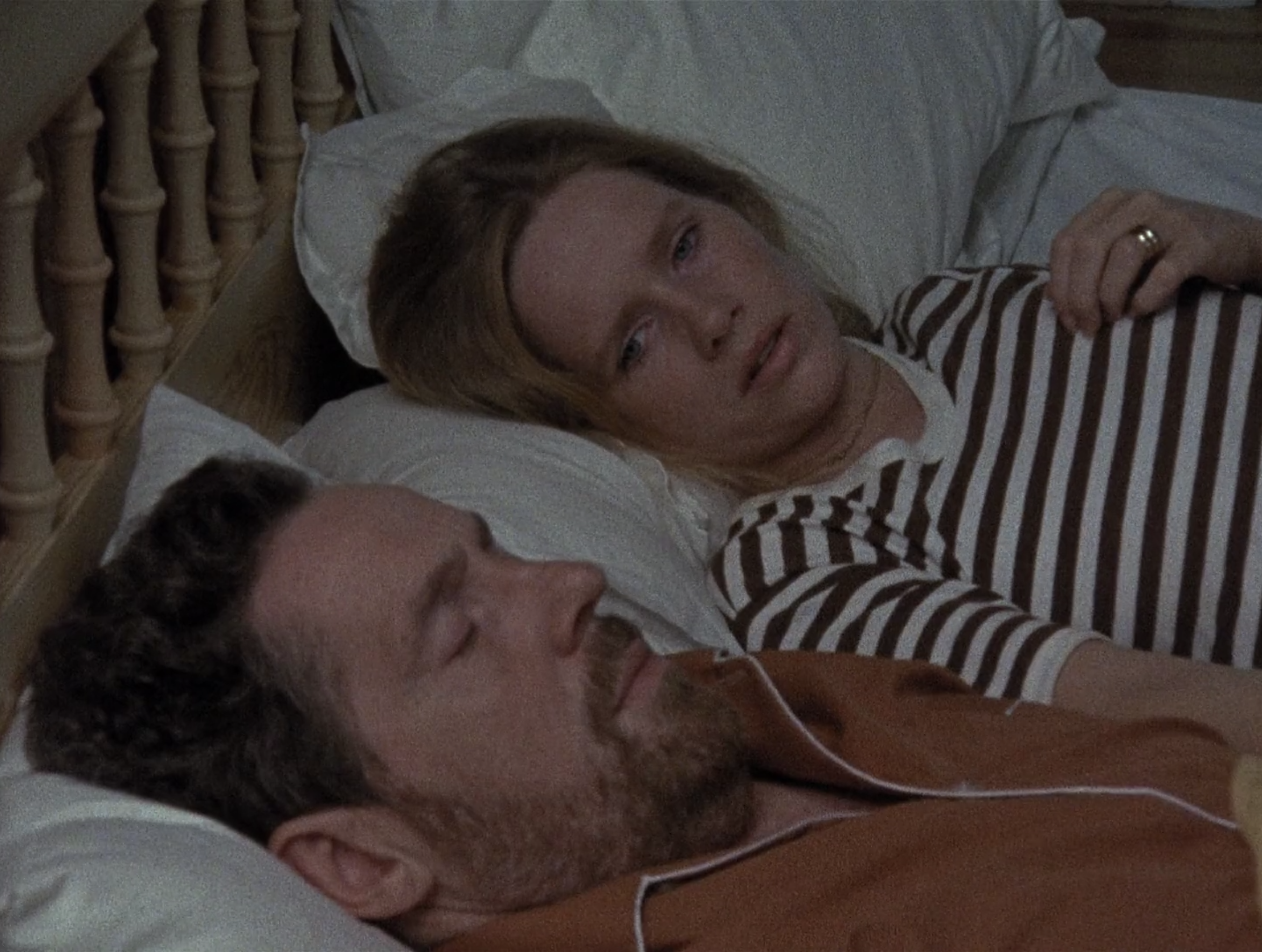

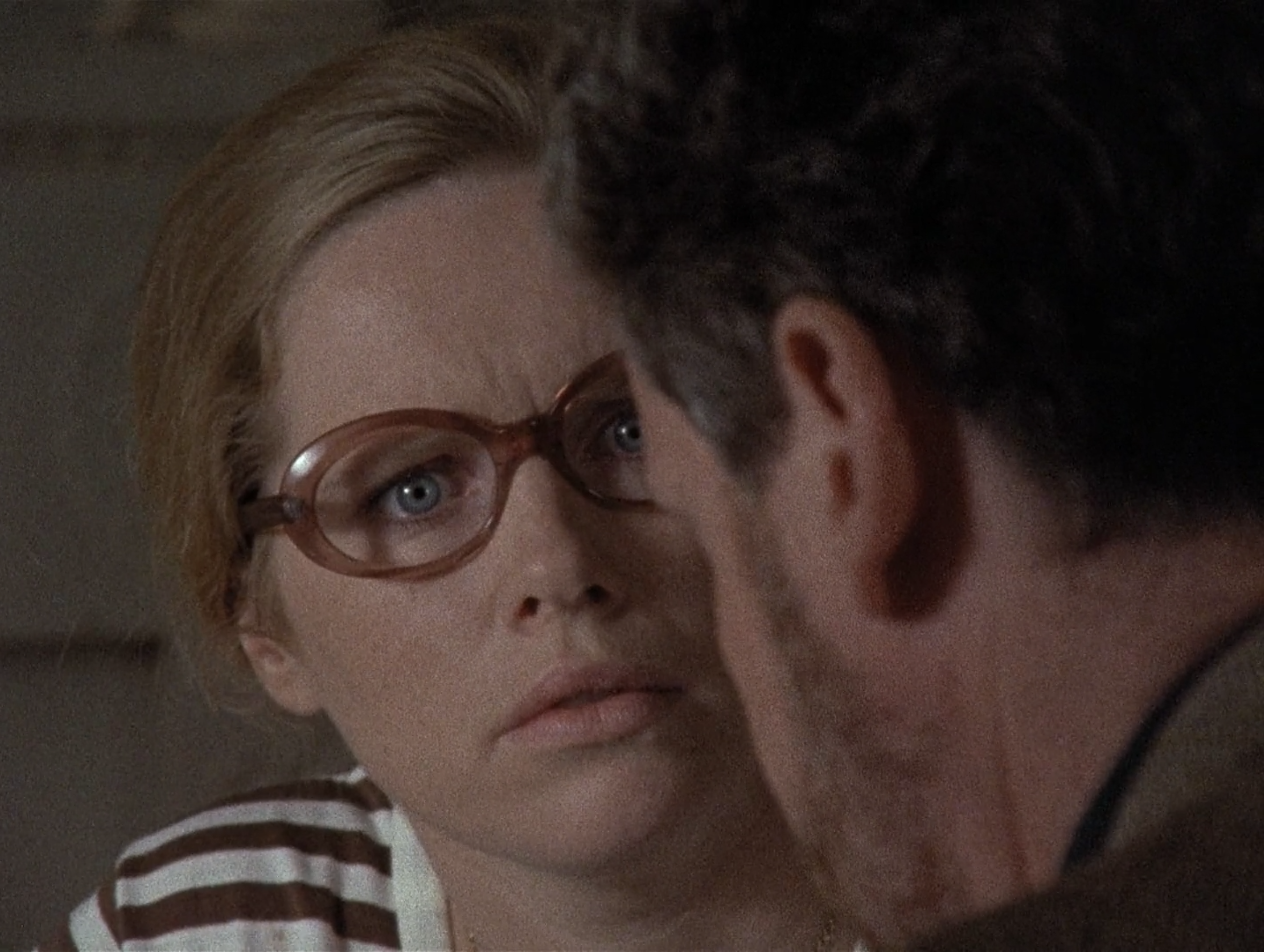

Despite being largely contained within small, minimalist sets though, Scenes from a Marriage is anything but stage-bound, as Bergman lifts it into a cinematic realm through his reliably sharp blocking bodies of faces. By cutting between wide shots and close-ups, he paints out the flow of isolation and connection between Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson. Doorframes often confine them in oppressive compositions, but both actors especially excel in tightly framed shots of their faces partially concealing each other, or otherwise slightly turning away from the camera in displays of restraint.

When emotional extremes run high at the climax of Marianne and Johan’s breakdown, the two collapse on the floor and begin to make love. As they finish, Bergman frames their faces resting against each other from an upside-down angle, literally turning this intimate expression of love on its head in the midst of a bitter feud. That she almost immediately tells Johan afterwards that all she felt was “lukewarm affection,” Bergman once again damages any hope that they might reconcile. Instead, it appears as if they are doomed to fluctuate between passion, civility, and loathing for eternity.

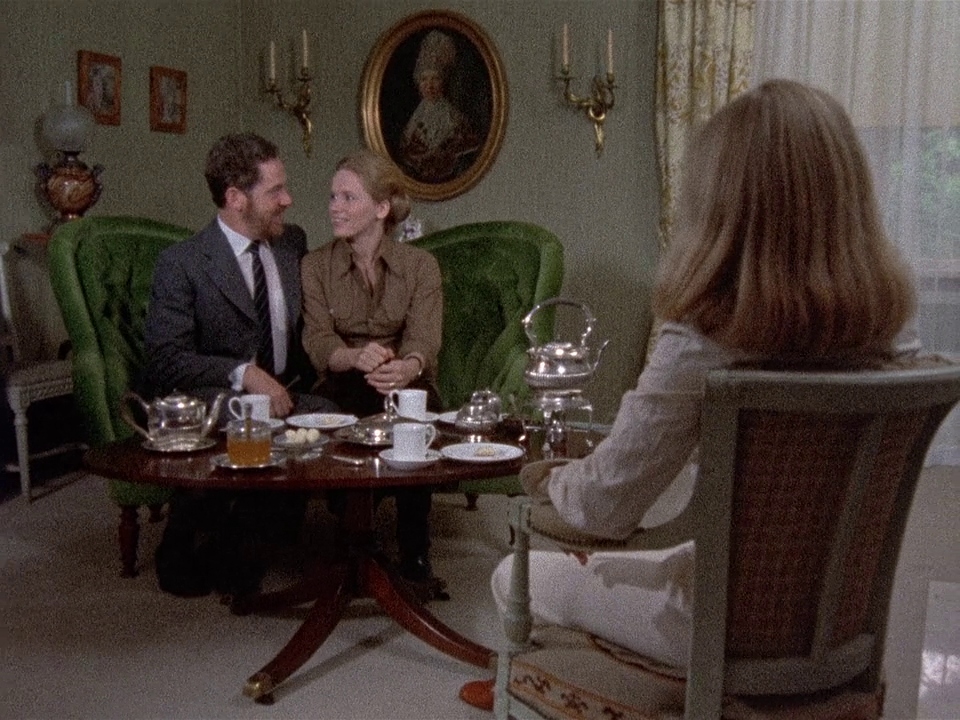

When Bergman’s camera pulls back from close-ups, these intimate interactions effectively turn into tennis matches, staging his actors symmetrically on either side of a bed, table, or couch as they trade barbs across the court. When Marianne begins to consider how their separation might be judged by her parents and friends, Johan impatiently shuts her down, demanding that this separation remains solely about their own personal issues, though even he cannot stand by his own rules.

One thing the couple can agree on at least is that Katarina and Peter’s troubles come from not speaking the same emotional language, and Johan and Marianne are eventually forced to admit that they are guilty of this too. Despite being highly intellectual individuals, they are self-described “emotional illiterates” who don’t understand a thing about their own souls. There is certainly some therapeutic growth here in recognising this, as Marianne reads aloud self-reflections from her diary on how she has hidden her true self to please others, but when Bergman shifts his camera to Johan, the only reaction we find is his sleeping face. When he awakes, he is apologetic and Marianne offers forgiveness, but the distance between the two has only widened.

So ingrained is this mutual miscommunication that even when Johan’s affair with Paula first comes to light, Marianne expresses total disbelief that anything was ever wrong between them. Ullmann’s eyes widen in fear and anguish, but most of all it is confusion we read on her face as Bergman’s camera lingers in close-up, tracing those tiny micro-expressions that flicker and disappear within milliseconds. Only now does Johan reveal that he had been desperate to get out of this marriage for years, and when Marianne calls her friends to tell them the news, they too admit their knowledge of his cheating. Clearly the reality of this marriage was evident to everyone but those wrapped up in its raw emotions, incapable of turning their perceptive minds inwards.

More than just an interrogation of a relationship, Bergman dedicates his series to examining the institution of marriage itself, and how the limitations of this contract restrict their bonds rather than nourish it. No longer do Johan and Marianne feel comfortable being their natural selves as husband and wife, as these rigid roles are thrust upon them by a one-size-fits-all culture. Their identities have been warped beyond recognition, and Marianne even reflects on how little the two resemble their younger selves who got married all those years ago.

“When I think of who I used to be, that person is like a stranger. When we made love earlier, it was like sleeping with a stranger.”

When Marianne considers remarrying too, Johan cynically articulates that she will just move through the same cycles all over again, finding only disappointment. He should know as well – he has not found love with his mistress, but just another kind of loneliness worse than being alone. Paula has ultimately turned out to be little more than a distraction from the inadequacy he feels from having his identity so closely intertwined with Marianne’s, and even in that role she is failing.

What are we to make then of the affair they conduct with each other so many years after finalising their divorce? Has the absence of a rigid contract freed them from their bitterness? There is evidently still a deep love there, as in Marianne’s sleep she is haunted by nightmares of losing her hands, and thus being unable to reach out to Johan for safety as she crosses a dangerous road. In this imagery though, she also implicitly blames herself for their separation. They might never recreate what they used to have, but there is some hope that they might forge something new outside the boundaries of marriage if they can somehow resolve the fact that they would be threatening their own current relationships. “We love each other in an earthly and imperfect way,” Johan reassures his ex-wife, putting to rest her concern that she has never felt true love.

When words can no longer do these lovers justice, all that is left for them is to sit in silence, whether it be out of contempt, understanding, or both. For all the acerbic quarrels that Scenes from a Marriage expresses so eloquently, it is through a pair of silent images that Bergman creates the most perfect representation of this relationship.

On the verge of signing their divorce papers, Johan sits across a table from Marianne with his head in his hands, and she reaches a hand out to comfort him, only to pause and withdraw before he notices. Later in the same scene as they sit on either side of a couch, he reaches out to hold her hand, and they finally make contact. Within this formal mirroring, Bergman reveals the chasm which exists between these “emotional illiterates”, turning their marriage not into a battle of husband versus wife, but rather lovers versus the space between them.

Scenes From a Marriage is available to stream on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1970s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

First of all, such a great website – so much to learn and understand about viewing film! I love this movie so much, but wanted to ask – have you seen the 2021 remake of this? It’s on HBO, and absolutely great in my opinion. It has a very intimate, stage-like quality to it – very elegant lighting design and genuinely makes their home a character itself. Of course, the director is no auteur like Bergman but I highly recommend it. Jessica Chastain and Oscar Isaac turn in jaw-dropping, career best work and its worth for that alone.

Thanks Adam, very much appreciate it! I have not seen the 2021 version, I’ve only read a few reviews. It certainly sounds interesting at least, even if it doesn’t touch Bergman’s.