Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 55min

David’s motivation to come to Sweden might come down to the recent archaeological discovery of a 500-year-old Madonna statue in a medieval church, but it is his affair with housewife Karin that compels him to stay. Between both these influences on his life, Ingmar Bergman draws strange, almost mystical parallels in The Touch – this Madonna figure bears a striking resemblance to his deceased mother, and later the breakdown of his relationship with Karin manifests physically in its decay, mixing Christian and Freudian symbolism. There is also something primal about those centuries-old, hibernating insects which now eat away it from the inside, reflecting the baby which later grows in Karin’s womb as a constant reminder of her failed relationships. Faith may not be at the centre of Bergman’s interrogation here as it has been so many times before, but its corruption is tangibly present in this divine motif.

No doubt this is a relatively new direction for Bergman at this point in his career, who for the first time writes a screenplay largely in English and casts an American in a leading role. Elliot Gould is volatile as David, violently swinging between overbearing affection and withdrawn melancholy, and offering a trauma-ridden counterpoint to Bibi Andersson’s apprehensive Karin. The barrier between them extends far beyond emotional misunderstanding – culturally, the two come from completely different places, with David bearing the scars of the Holocaust concentration camps, and Karin knowing little of the world beyond her Swedish town.

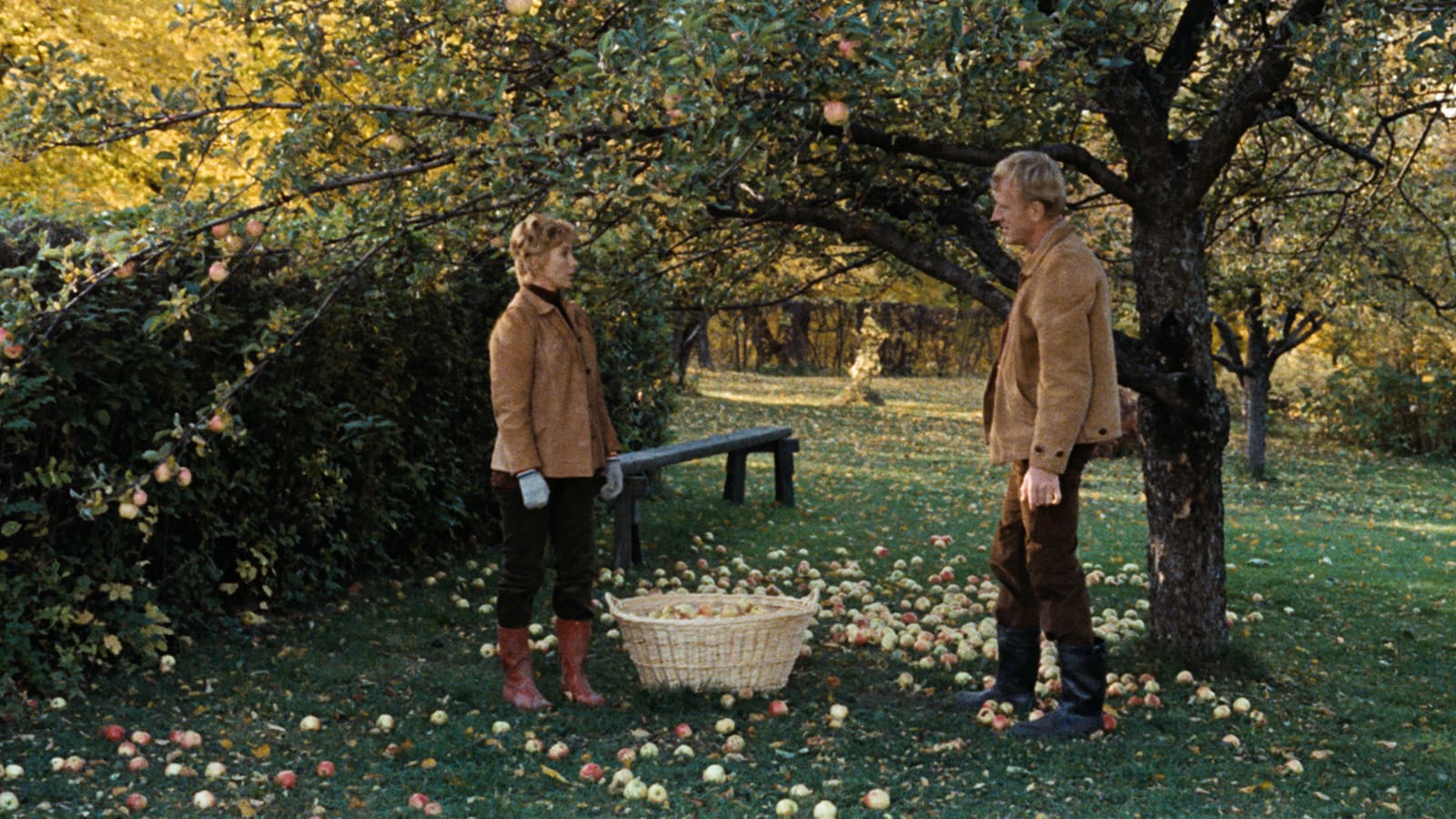

Given that Bergman was targeting this film to American audiences, it isn’t surprising that he shapes its style to a more typically Nordic aesthetic than usual, lingering on the delicate scenery of historical villages and autumnal foliage. When it comes to the upbeat folk score of piano and woodwinds, Bergman falters a little more, striking a jarring tone that doesn’t always match the film’s pensive sorrow. The Touch possesses neither the stylistic grandeur nor the allegorical richness of The Virgin Spring, but these elements still work in service of a similar Garden of Eden metaphor, carefully designing an idyllic paradise that is slowly leeched of colour the longer David is around to exert his corrupting influence.

If David represents Satan in this case, then it is only due to the influence of evil from elsewhere in the world. With most of his Jewish family falling to the Nazi regime, he has been left with a blend of unresolved traumas and toxic behaviours, leaving him to unintentionally inflict his own trauma upon others. The notion of original sin is even suggested in the mention of a congenital condition that he inherited from his ancestors and will pass onto his children, and serpentine imagery often surrounds him in Bergman’s mise-en-scène. There is no doubt that he is the one who brings temptation into Karin’s life, but we cannot brand him as totally evil – merely a sufferer of a greater historical tragedy that even a neutral country such as Sweden cannot keep from penetrating its borders.

It stands to reason then that Max von Sydow is the God figure in this tale, with Andreas’ occupation as a life-giving doctor standing in contrast to David’s archaeological fascination with death. His home life with Karin is peaceful, if not particularly passionate, and when she contemplates following David to London he effectively ousts her from the garden. Gone are the warm colours of falling leaves and sunny skies, and in their place are the frigid landscapes of a harsh Swedish winter.

Even with some decent cinematographic work from Sven Nykvist on display though, The Touch sits among Bergman’s more stylistically plain efforts, grating up against a screenplay that is often awkwardly written. Gould fares a little better than Andersson here who struggles with her dialogue, and the isolated choice to depict some letters through talking heads marks a clumsy formal flaw. This messiness continues right through to the very final scene, jarringly ending at a climactic peak of emotion with little resolution, and unfortunately detracting from its gorgeous wide shot on a riverbank which is otherwise one of the film’s strongest compositions.

Nevertheless, The Touch is not a failure by any means, but simply a lull between two fruitful periods of Bergman’s career. On one side, his magnificent run through the 1960s set him up as one of history’s truly great directors, while in the 70s he would push his formal experimentation further with Cries and Whispers and Scenes from a Marriage. Regardless of how this measures up in comparison, his wielding of theological symbolism to interrogate a broken love triangle is deft, bitterly driving the Madonna’s image of degraded goodness between his doomed, corrupted lovers.

The Touch is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV.

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green