Alfred Hitchcock | 1hr 41min

The most obvious dramatic tension that emerges in Notorious comes from its thickly plotted conflict of romance and thriller conventions, tugging our central lovers between deep passion and cold, methodical pragmatism. This riveting narrative of high-stakes subterfuge could be read through the lens of either genre, especially when the initial honeymoon period between Cary Grant’s U.S. agent and Ingrid Bergman’s German defector is interrupted by official orders for her to seduce and spy on a suspected Nazi affiliate, Alex Sebastian. Their breakup is as clean as can be under these circumstances, with Devlin especially putting up a front of stoic impassivity, but Alfred Hitchcock’s fractured blocking betrays their mutual, wounded sorrow. Even the champagne bottle that Devlin bought to share with Alicia over a romantic dinner is suddenly missing, and thus their evening comes to an abrupt end.

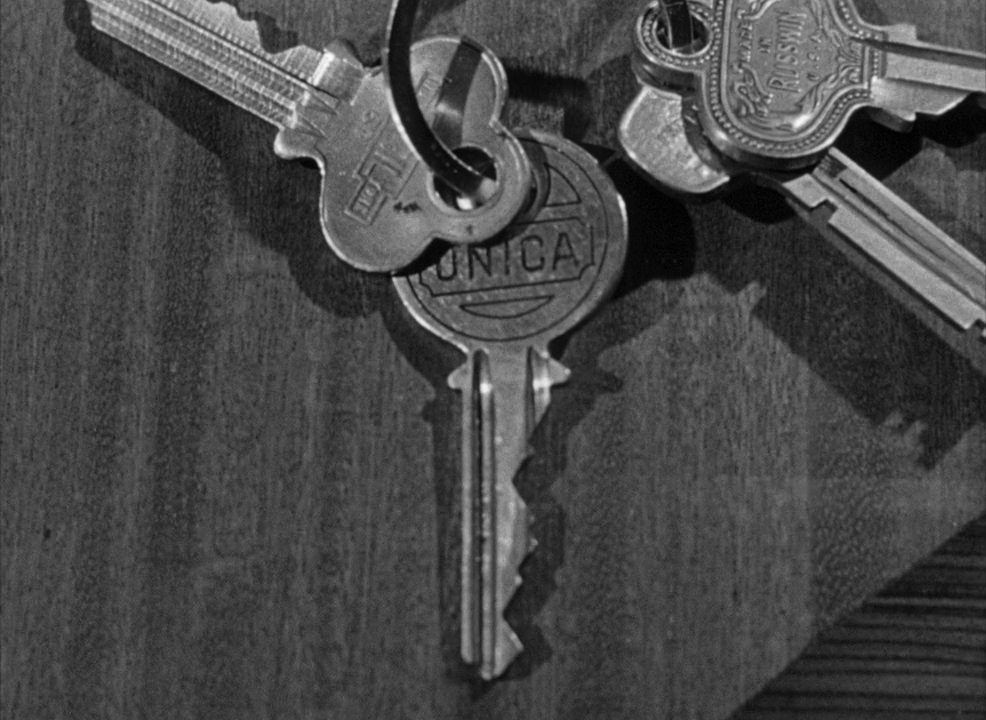

It is in that final detail though that Notorious’ most robust motif begins to manifest, developing a tension through layers of formal symbolism that is far more intricate than its overarching genre clash. It begins with Alicia’s alcoholic lifestyle and reckless drink driving, allowing her an escape from the guilt of her father’s Nazi convictions, but wine bottles are also integral to the conspiracy she investigates for the U.S. government. One of Alex’s associates grows agitated at the sight of one specific bottle during dinner, and later Alicia discovers that her keyring grants access to every room in the house except for the wine cellar, making it apparent that these symbols of upper-class aristocracy hold darker secrets than one might expect. In one lush ball scene, Hitchcock even uses regular cutaways to an ice cooler of bottles to drive up the suspense, placing a time limit on her and Devlin’s investigation of the cellar by tracking the party’s dwindling supply.

Indeed, these intoxicating refreshments which promise a few hours of light-hearted fun only ever lead to danger in Notorious, and could potentially even instigate a third World War given the uranium ore contained within them. This is far from the end of Hitchcock’s beverage motif too, as once Alex and his mother discover Alicia’s loyalty to America, innocuous servings of coffee also become deadly weapons. Glasses and bottles are swapped out for teacups in Hitchcock’s mise-en-scène here, dominating and obstructing shots that leave her shrunken in the background, while she remains unaware of the poison hidden in their contents.

Even more astounding are the close-up tracking shots which suspensefully trace the movements of these cups across rooms, from the moment Alex’s mother fills them with coffee to their eventual contact with Alicia’s lips. The murderous operations of these scheming Nazis are elegantly lethal, incrementally weakening her health over time, and Hitchcock’s camerawork is every much their equal in precision and sophistication. It reaches an enormous stylistic peak in a crane shot that sweeps us from a wide frame of Alex’s opulent entrance hall into a close-up of Alicia’s hand grasping a stolen key, and often punctuates dramatic beats with subtle push-ins on faces, but even beyond these agile motions his visual storytelling is remarkably dextrous.

At its most potent, he lands us within Alex’s own silent investigation of the wine cellar, excising dialogue completely as he follows a trail of clues – the lost key mysteriously back where it belongs, the tampered order of bottles, a broken seal, and shards of glass swept under a shelf each point towards Alicia’s guilt. The editing is precise throughout, and the pacing measured, suspensefully building up to Alex’s major turn. His tightly framed face is tilted down in shadow when he finally comes to his mother with this revelation, and as he confesses, he rises it very gently into the light.

“I am married to an American agent.”

For Alex’s mother who has mistrusted Alicia from the start, it is enormously vindicating for her suspicions to be proven right, yet this development may be even more satisfying for Hitchcock who revels in the Freudian insecurities of their relationship. Her protectiveness over Alex has been simmering with jealous undertones ever since he invited this other woman into his life, so now with her son fully on side, she relishes killing off his lover in a slow, painful manner, effectively becoming a slightly less twisted version of Norman Bates’ mother in Psycho.

In a strange way, this complex mother-son relationship also reflects the stifled romance between Devlin and Alicia, who correspondingly hold onto an emotional repression keeping them from expressing themselves honestly. It is often much easier for them to deny the existence of impractical feelings altogether so that everyone can move on with their work, yet in Notorious it is also those who deceitfully conform to rigid, impersonal standards that come closest to losing everything.

For our main characters to be saved then, they must allow their truest feelings to break through their cool exteriors, and Hitchcock approaches these arcs with an incredible formal mirroring between Notorious’ first and final acts. Alicia’s hangover early in the film blurs and spins the frame when Devlin comes to her with a job offer, and as he comes to take her away from Alex’s mansion, her vision is once again impaired. The initial meeting between Devlin and Alicia where conversation turns to alcohol and love is similarly echoed here as well, as they discuss her poisoning, and he confesses his feelings.

Tentatively, they move downstairs in full view of Alex’s co-conspirators, who now peer suspiciously through a door at their compromised friend. The scene is reminiscent of that which previously saw a judge sentence Alicia’s father to prison, and now frames these Nazis as the judges of Alex’s own fate. Even the night-time drive which saw Devlin use his government position to save a drunken Alicia is inverted at this climax, where he lies about his identity to make a safe getaway in his car. No longer is he just a bureaucrat looking to use her for work, but a man so deep in love that he will put himself in harm’s way to keep her safe.

In Notorious, this is the reward that comes to those who reconcile their subconscious desires with their conscious actions, invigorating its narrative with a muscular formal structure. Grant might be given the meat of this character development, but Bergman shines even brighter for the dazzling highs and profound depths that Alicia reaches, eventually finding sincere happiness as her true self beyond her alcoholic indulgences and deceitful double life.

It is not Devlin and Alicia who Hitchcock sticks us with in the final minute of Notorious though, but Alex, left to face the consequences of his actions and saunter through the large doors of hell. For a few seconds it looks as if the camera might follow him too, until they close in our face with a final clang. Hitchcock does not need to tell us what comes next. It is all there in the subtext of his collaborators’ accusing stares. Even in this den of humanity’s greatest evil, there is no haven for liars – merely a sad, pitiful end to a life of dishonesty.

Notorious is currently streaming on Tubi TV.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1940s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green