David Lynch | 1hr 29min

The wild shock of hair that leaps up off Henry Spencer’s head in Eraserhead has become somewhat of an icon for David Lynch’s debut film, exploding from his dazed expression like an electric current illuminated in harsh black-and-white light. Like Charlie Chaplin, our main character is a man of few words who waddles around industrial urban landscapes, though unlike the silent comedian there is no spring in his step. His existence in Lynch’s dystopian modern city is joyless even before he meets the malformed product of his intercourse with Mary X, but as he takes on the daunting task of fathering a child, he is only confined further by his anxious nightmares. Suddenly, his entire purpose is dedicated to a tiny, wailing creature, and his claustrophobic apartment has become his entire world.

Within Lynch’s disturbing creation, Henry is not a vivid character filled with a rich inner life, but an empty vessel of melancholic frustration, absorbing whatever fears we imprint upon him. Even more archetypal all those secondary characters who are given titles such as the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall and the Man in the Planet in place of real names, which might incidentally imbue them with depth. As far as we are concerned, they do not exist outside of Henry’s solipsistic prison.

Neither does Lynch offer much explanation for what they represent, leaving us to question whether the puffy-cheeked Girl in the Radiator might be a symbol of death’s welcome relief, or Henry’s ideal woman. That she sweetly sings the haunting seduction “In heaven, everything is fine” to him and crushes large, sperm-like creatures beneath her feet could suggest either, or perhaps both. All that we know is that is that within this existential dream of mutant babies and urban isolation, it is the raw impression of Eraserhead’s surreal imagery which carries far more impact than any attempts to derive its literal meaning.

When measured up against a young Lynch at the start of his career, there are so few filmmakers who can craft cinematic surrealism as provocative as this. The evidence of this being his first feature is apparent in the meagre $100,000 budget he had to work with, though not even this is a hindrance to the incredible imagination on display, much of which is poured into grotesque practical effects. Clear parallels can be drawn to contemporary David Cronenberg who would also begin working around the same time at the peak of the American New Wave, and though one would veer more into body horror and the other into surrealism, there is a relatively even intersection of both here.

Also integral to this anxiety-ridden slow burn is the low-level hum of machinery and crying, constantly droning through its sound design. It is often as if Lynch has filtered the incidental noises of a near-deserted city through several layers of consciousness, until the faint creaking of factories, the hissing of a radiator, and the muffled patter of rain combine in muted distortions of reality. Considered with his bleak monochrome photography which mesmerises in its offbeat framing, Lynch effectively crafts entire dream worlds branching off from Henry’s singular fear of fatherhood, often with barely more than a few lines of dialogue.

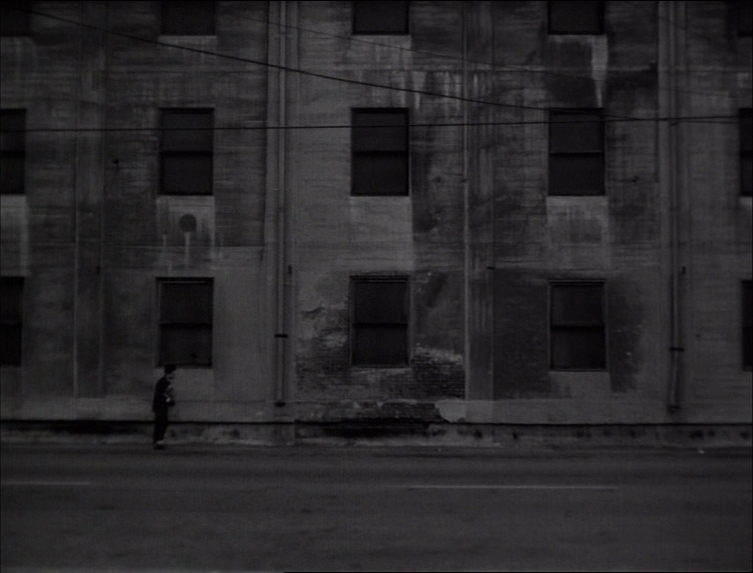

Most of all though, it is Lynch’s design of the deformed baby that stirs up a primal disgust in Eraserhead, and which in turn induces Henry’s self-loathing recognition that he is capable of producing something so incredibly vile. It is also a vaguely humanoid extension of those giant sperm creatures that frequent Henry’s nightmares, appearing under his bedsheet and writhing around in stop-motion animation. This child is utterly dehumanised in his eyes, no more than a low-level organism that can barely support its own existence.

The stress that comes with caring for this monster is a whole other ordeal too – it only takes a second while Henry is looking away from it to suddenly develop measles and catch some respiratory virus that leaves it wheezing. Even worse are those sleepless nights spent listening to its incessant mewling, driving Mary to pick up and leave, and pushing Henry to harbour an even deeper resentment of his repulsive offspring.

On a sociological level too, there is a deep fear embedded in Eraserhead of what Henry’s future might look like should he fully adopt the mantle of patriarch and begin his own family, illustrated in Mary’s uncomfortable home life. The disjointed rhythms and vague non-sequiturs of their conversations paint out lives of total banality, wilfully oblivious to the peculiarities seeping in – the half-alive roast chicken for example, or the direct sexual advances of Mary’s mother. The psychosexual depths of modern American families would later become even more central to Lynch’s interrogations a decade later in Blue Velvet, but they also mark the point in Eraserhead where its dialogue is densest.

Elsewhere the influence of silent films is tangible; specifically the 1929 surrealist short Un Chien Andalou, where Luis Buñuel innovated a cinematic language of dream logic that Lynch would develop even further in his foggy, discontinuous editing. Every bit of his visual storytelling measures up against the greatest films of that era, drawing visual connections between Henry and his child in one horrific nightmare that sees the baby grow out of the neck stump where his head has fallen off. The fear of one’s self-image being consumed by parenthood is conveyed in a series of sinister images far more evocative than any passage of dialogue Lynch might have written instead, and when the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall later sees this same mutated hybrid in Henry’s place, these terrors continue to reverberate through the film’s formal structure.

When his decapitated head is taken to a factory and manufactured into erasers, there is no harm in pondering whether this scene implies the erasure of Henry’s identity or his desire to rub out his own mistakes, but it would be foolish to dwell too much on the specifics of Eraserhead’s meaning. Lynch is a master of provoking those ugly, primal impulses which we shy away from, and that often can’t be captured in words alone. The jarring shift from Henry gruesomely killing his baby to the heavenly comfort he finds in the arms of the Girl in the Radiator produces an unsettling peace in the film’s final minutes, and one that cannot be easily reconciled within traditional narrative conventions which might position him as our hero. Instead, Lynch would much rather let us consider Henry as a vision of humanity at its weakest, falling prey to psychological influences that have taken terrifying physical form in his world. From this dark, tortured perspective pushed far beyond the limits of mental forbearance, there is no nightmare more profoundly frightening than young parenthood.

Eraserhead is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1970s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Cult Classic That Influenced Robert Eggers Is on HBO Max – HollywoodNewsHub.com