Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 41min

Years after Ingmar Bergman’s chamber drama The Passion of Anna was released in 1969, Liv Ullmann was quite frank in admitting that he wasn’t sure what he wanted to express through it, presumably due to the huge personal turmoil that was unfolding between both director and actress on the verge of their breakup. The messiness that resulted is no doubt evident in certain creative choices, with Ullmann’s titular character being largely absent in the first half, and Bergman bringing her back in halfway through with a jarring time jump. At the same time though, this uncertainty also instils his direction with an improvisational quality that he has often kept a distance from in his career, bringing a raw vulnerability to this study of dishonest lovers.

The influence of the French New Wave had slowly been pushing Bergman closer to deconstructions of cinema throughout the 1960s, but perhaps with the exception of the magnificently postmodern Persona, there is little as bluntly self-referential as the interviews he conducts with his actors here. These come in the form of four interludes clearly breaking away from the main narrative and positioning his cast as avatars who know these characters on a far deeper level than any friend, lover, or even themselves.

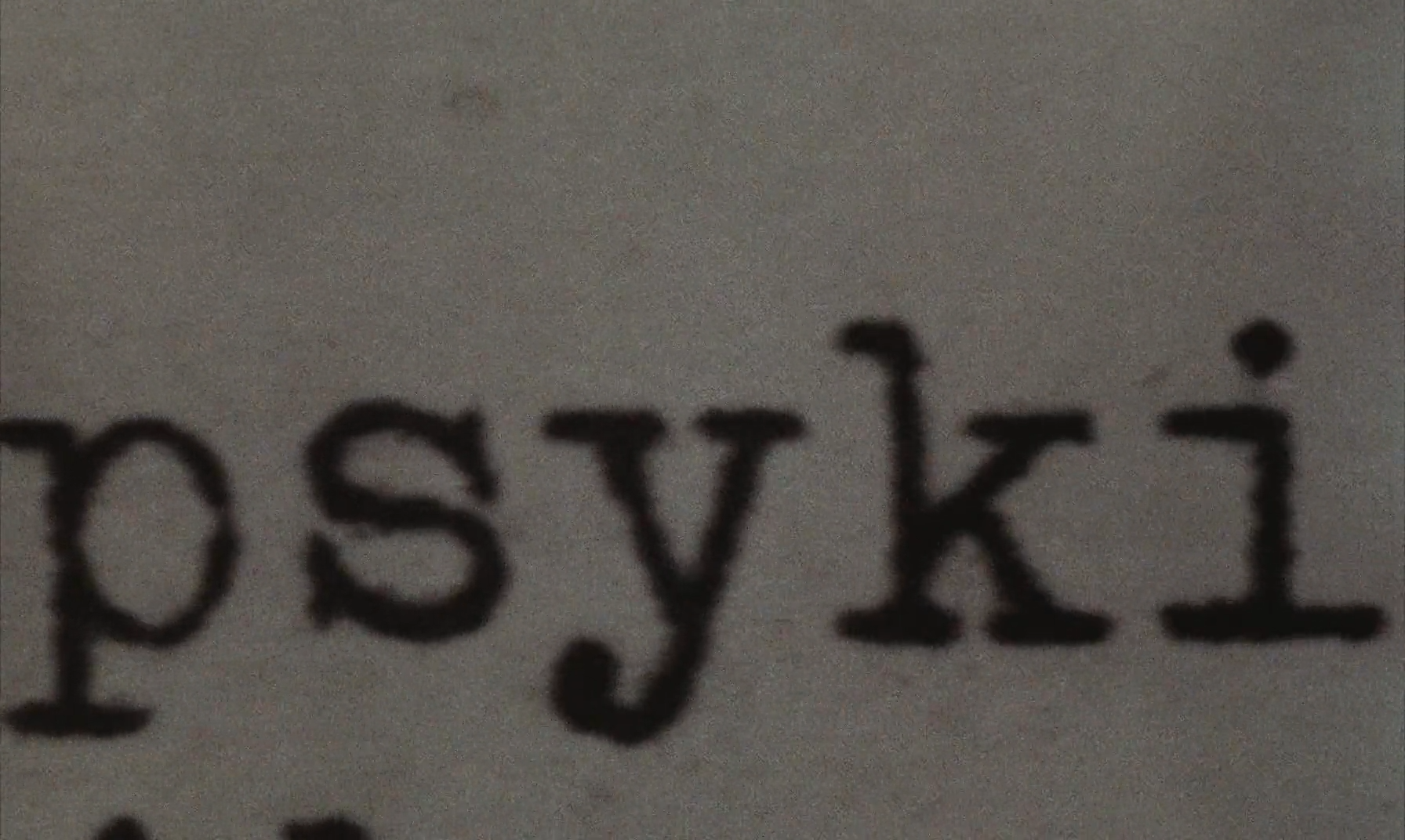

Max von Sydow is the first of these, speaking of the lonely Andreas Winkelman as a recent divorcee shamefully trying to hide his identity and destroy his means of expression. He stands in sharp contrast to Ullmann’s Anna who claims to desire the absolute truth of her relationships, yet takes refuge in lies, realising too late that reality is uglier than she would like to believe. Bibi Andersson and Erland Josephson respectively play troubled spouses Eva and Elis, one being “a woman who can no longer cope with the fact of her own disconnectedness,” and the other an amateur photographer who believes anyone horrified at human madness is a hypocrite. Like so many of Bergman’s films, his rural home island of Fårö plays host to this drama, as its physical isolation pushes these characters to commit cruel, heartless acts against each other.

As for the mystery of who is killing the animals on this island, Bergman purposefully leaves enough ambiguity to suggest that it could be anyone – perhaps with the exception of Andreas who saves a hanging puppy. The clearest suspect in the eyes of the local police and residents is the mentally ill loner Johan, though after he is driven to suicide by a violent mob, it soon becomes apparent that he is innocent. More than anything else, this thread of murders injects The Passion of Anna with menacing undertones, suggesting a desire for sadistic violence in the most ordinary people.

If we are to pin the killings down to a single character though, then perhaps we should look to Anna. Just as the identity of the animal killer is kept uncertain, so too is the truth of her past as a wife and mother, which she asserts was a perfectly happy life before her family perished in a car accident she accidentally caused. After discovering an old letter from her husband also named Andreas, von Sydow’s Andreas Winkelmann sees through the façade – their relationship was full of “complications, which in turn will trigger terrible emotional, agitation, physical and psychological violence.” Often when Anna proclaims her belief in total honesty and “striving for some form of spiritual perfection,” Bergman cuts away to these typed words that have imprinted themselves in Andreas’ sceptical brain, eroding our trust in her words.

That said, it is also perfectly evident that Anna has convinced herself of the lies she has constructed, and so in a strange way there is still a profound honesty in Ullmann’s performance. In one five-minute close-up, she speaks with sincerity about the cliché of two people becoming one through marriage, and then as her monologue turns to the car crash, her head slightly tilts and she turns her glassy gaze just beyond the camera. This is the second of Bergman’s films to be shot in colour, but the first featuring Ullmann, and through this vibrant photography the vivacity of her bright blue eyes can finally be fully appreciated in all their expressive beauty.

Further revealing the depths of Anna’s lingering trauma are her night terrors. The first time they appear we distantly hear her screams from Andreas’ bedroom, though later we see them for ourselves as Bergman’s camera enters her mind. Up to this point he has crafted a rich palette that has shifted from warm summer tones and artificial magic hour photography into the cold dead of winter, though here he reverts to the austere black-and-white imagery of his previous films. Shame draws the closest comparisons of all to the bleak, war-ravaged scenes of Anna sailing across the ocean on a refugee boat, meeting a woman whose son is being executed, and fruitlessly begging her for forgiveness, though Bergman is more cryptic with such surreal symbolism as this. The guilt that haunts her is deeply layered, and only stokes further questions regarding the role she played in her husband and child’s deaths.

With tensions as thick and unresolved as these, it is only inevitable that they will spill over into her relationship with Andreas, and a full-blown expose of each other’s lies violently erupts. If we didn’t have any suspicions by this point that Anna had purposeful intent in killing her family, then they are certainly piqued now as she runs the car containing her and Andreas off the road, with only his quick reflexes saving them both. Both sides frustrated and ruined by the impasse they have reached, Anna leaves Andreas by the side of the road, and Bergman slowly zooms from a long shot into his nervous pacing. “This time he was called Andreas Winkelman,” the running voiceover enigmatically concludes, linking him back to Anna’s deceased husband and suggesting a universal plight that plays out in variations of the same story.

It is far from Bergman’s strongest ending, and The Passion of Anna does not exactly possess the formal strength of his most avant-garde works, yet there remains something compelling about his wrestling with these complex characters dynamics, straining against the violent assault of outside forces. With both Hour of the Wolf and Shame sharing these concerns, a loose thematic trilogy forms around these films, collectively testing the psychological stability of Ullmann and von Sydow’s cynical lovers. Although this is the weakest of the three, watching Bergman deconstruct his own interpersonal vulnerabilities with imperfect honesty offers absorbing insight into the limits of our humanity all the same.

The Passion of Anna is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1960s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green