David Cronenberg | 1hr 29min

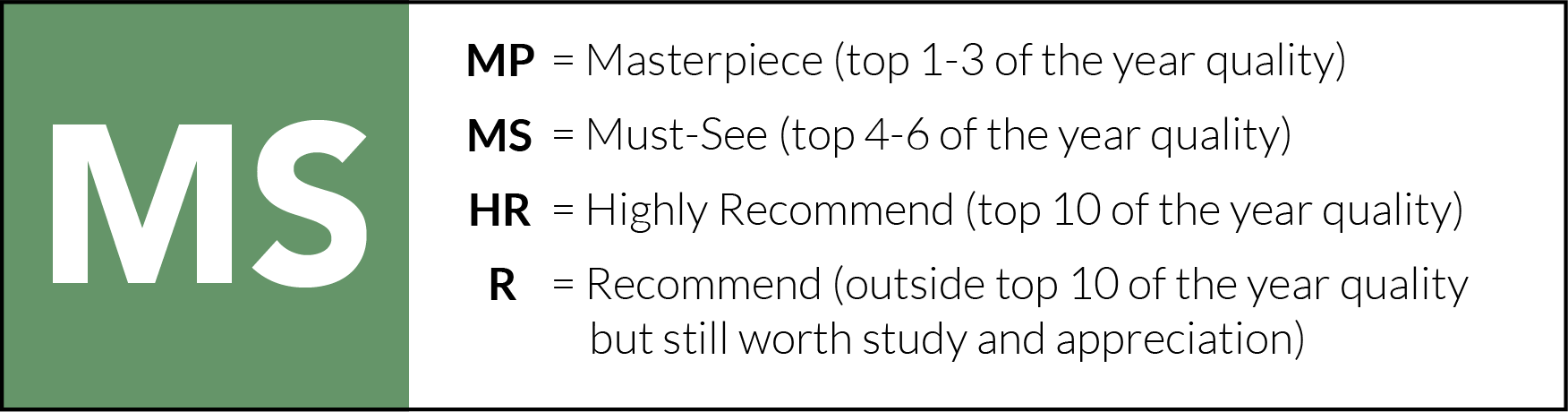

Once the factions of warring conspirators vying for control of a single television station CEO’s mind come to light in Videodrome, the question of how real his hallucinatory visions are becomes entirely irrelevant. On one side, the producers of the titular snuff program rail against the gratuitous, sensationalist media deemed poisonous to North American culture, and thus plan to broadcast their show through deadly radio waves that cause brain tumours in their degenerate audiences. On the other side, media scholar Brian O’Blivion firmly believes the transmutation of life into moving images is the future of humanity, making depraved programs such as Videodrome little more than an extension of our reality.

It is an inspired touch too that in death he has essentially transcended to this immortal state of being, keeping up public appearances through self-recorded VHS tapes. He may speak in long-winded passages and metaphors, but his philosophy is deceptively simple.

“The battle for the mind of North America will be fought in the video arena – the videodrome. The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore television is reality, and reality is less than television.”

When it comes to those aforementioned hallucinations then, does the distinction between Max Renn’s reality and perception really matter? O’Blivion might assert that when a brainwashed Max commits multiple murders at Videodrome’s climax, blows a hole in the side of the building, and walks out onto a calm street of passers-by who don’t throw so much as a second glance, we must accept the validity of what we just witnessed. After all, “there is nothing real outside our perception of reality” the scholar claims, encouraging Max to accept his distorted, subjective experiences as absolute truth. This frivolous ideology may be dangerous in its flattening of a complex world into two dimensions, and yet as a prediction of our culture’s direction, it is also remarkably prescient.

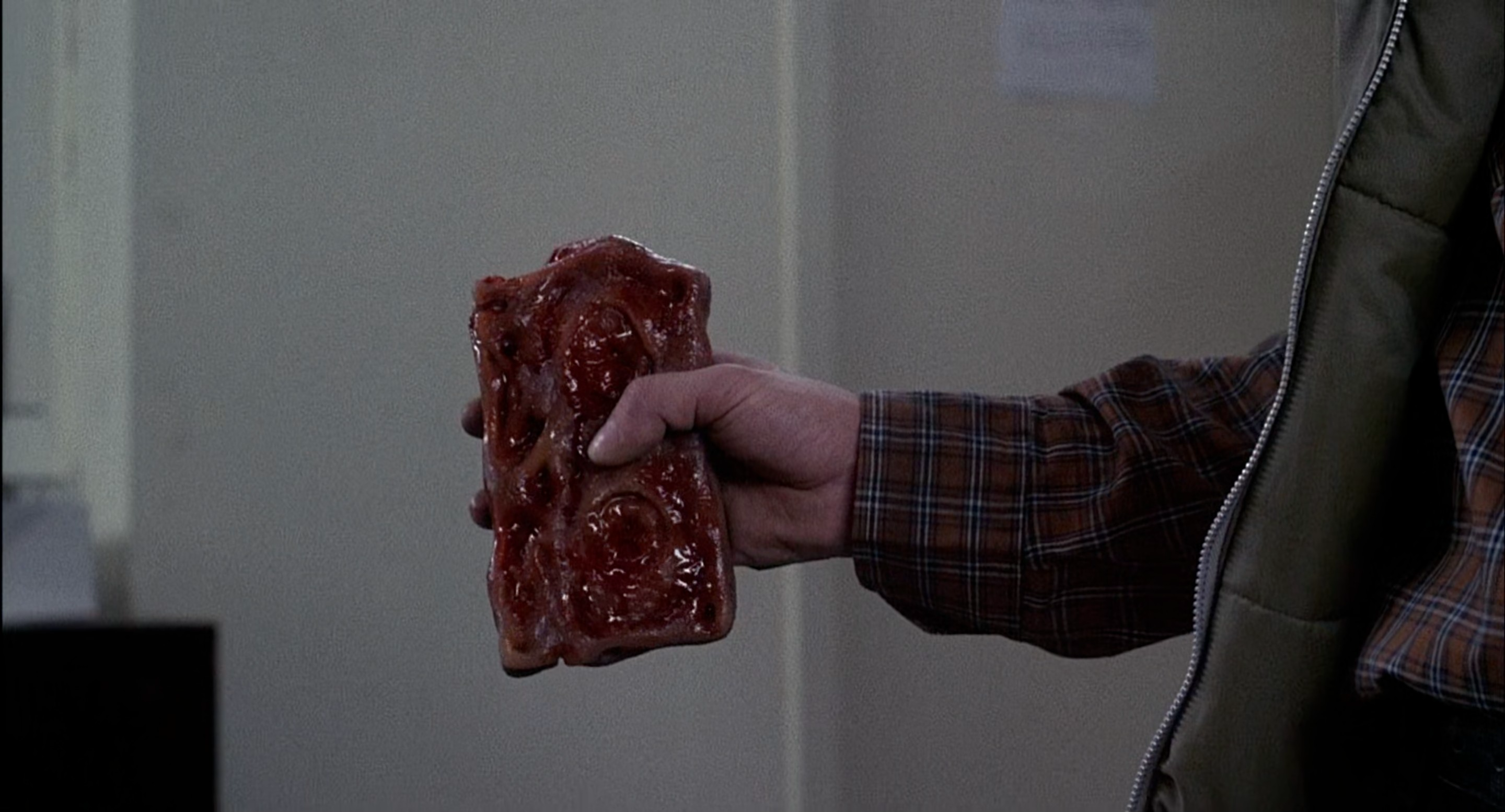

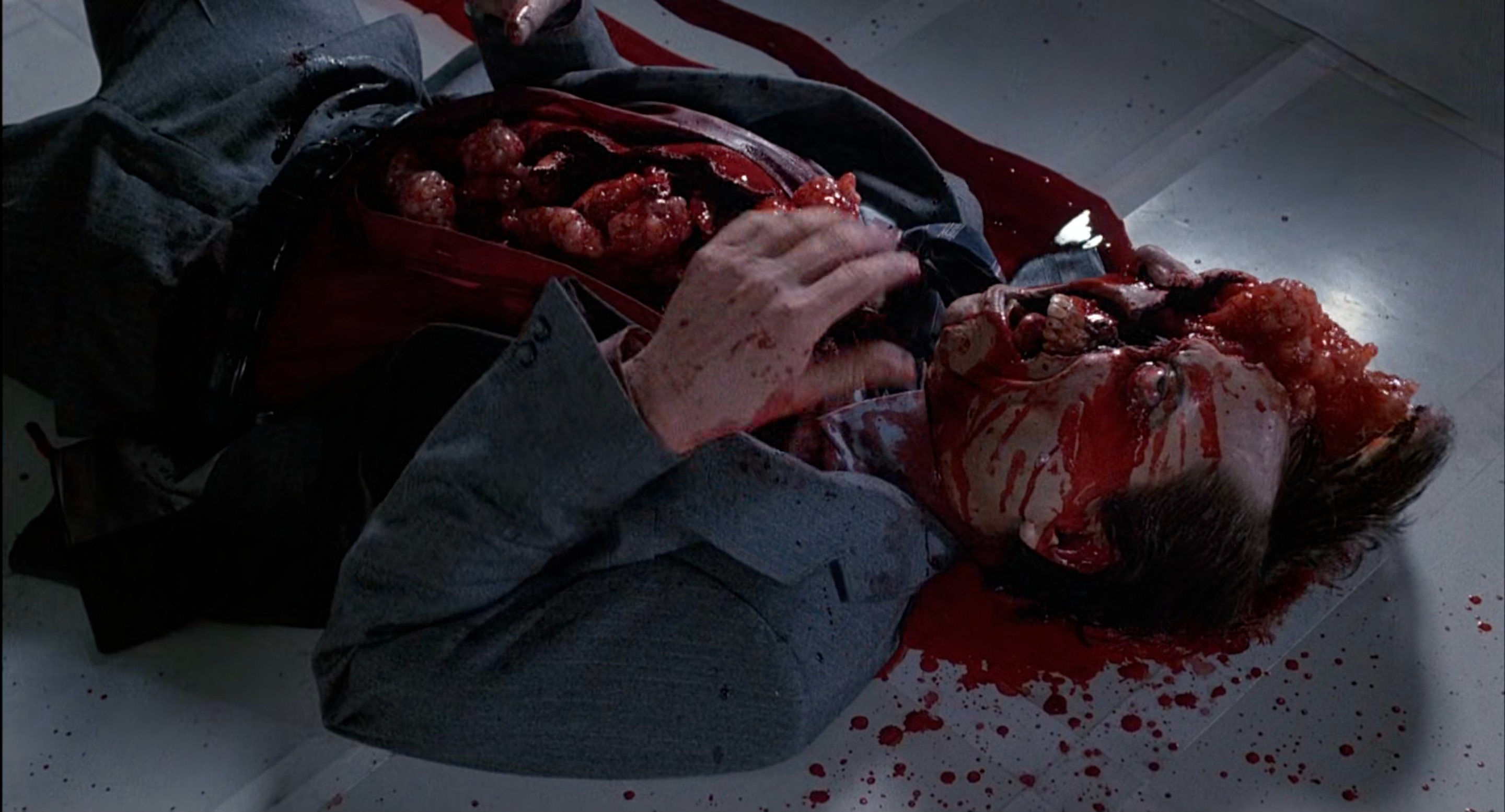

David Cronenberg’s blending of such intellectual musings on modern mass media with imagery as bizarrely grotesque as that which defines Videodrome’s visual aesthetic makes its dire warnings all the more visceral, and marks a triumphant success of filmmaking for the young auteur. He had certainly made a name for himself previously as a dabbler in high-concept body horror, but his reign over the subgenre was properly solidified here, uncovering its potential to not just represent, but to analytically examine the terrifying fragility of the human body.

As it manifests in Videodrome, the illegal program’s depiction of real torture and murder is only the beginning. The content of its episodes always unfolds in the same red room against a clay wall, promising lust and danger in its very design. Max, who is thoroughly desensitised to the debauched schlock his television station has been broadcasting, initially refuses to believe that its violence is authentic – yet he is intrigued. These awakened desires manifest in his new relationship with radio host Nicki as sadomasochistic foreplay, erotically cutting and piercing her skin, and soon enough his psychosexual inhibitions come crumbling down as he deliriously imagines them making love in the Videodrome room.

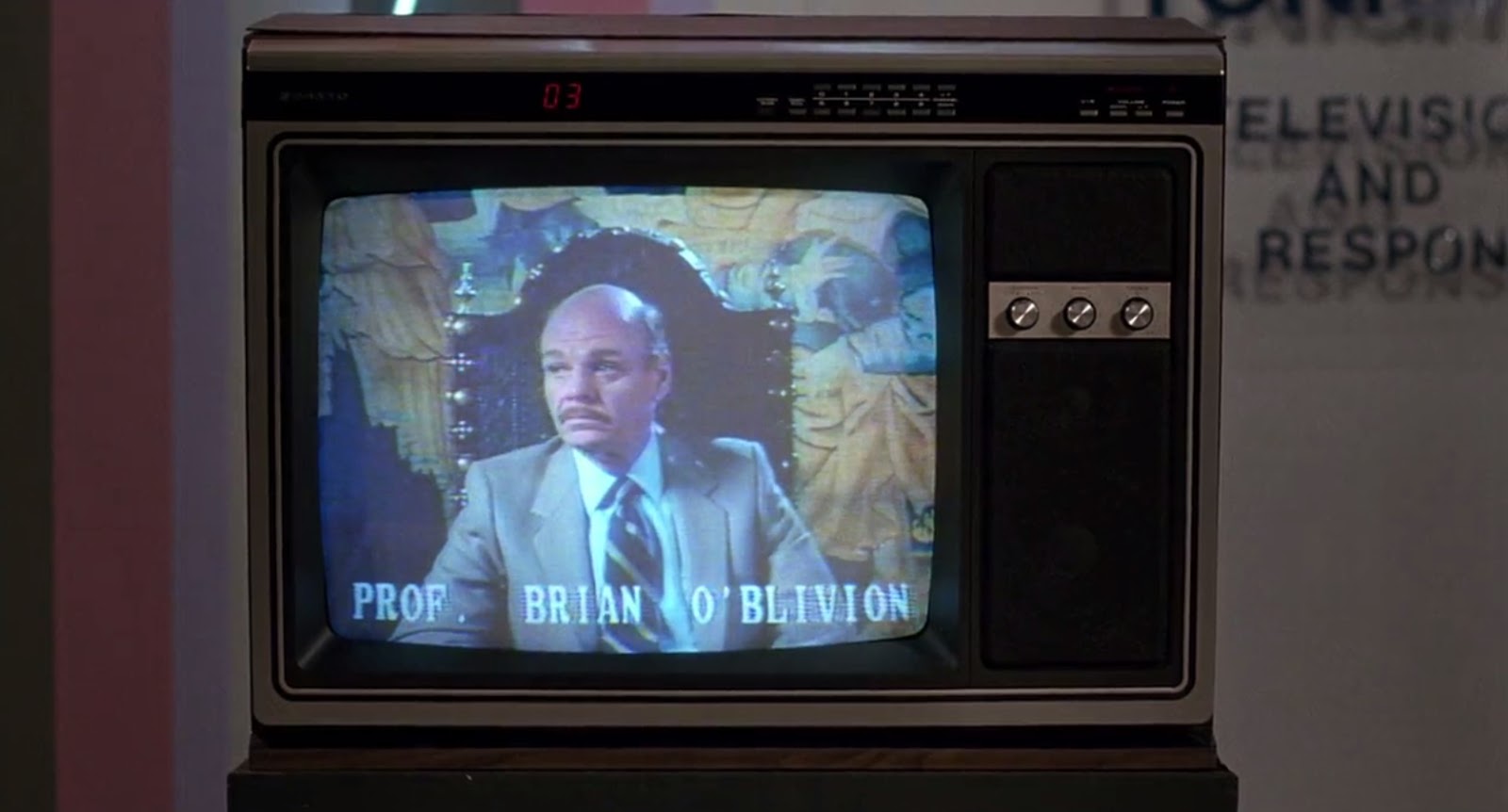

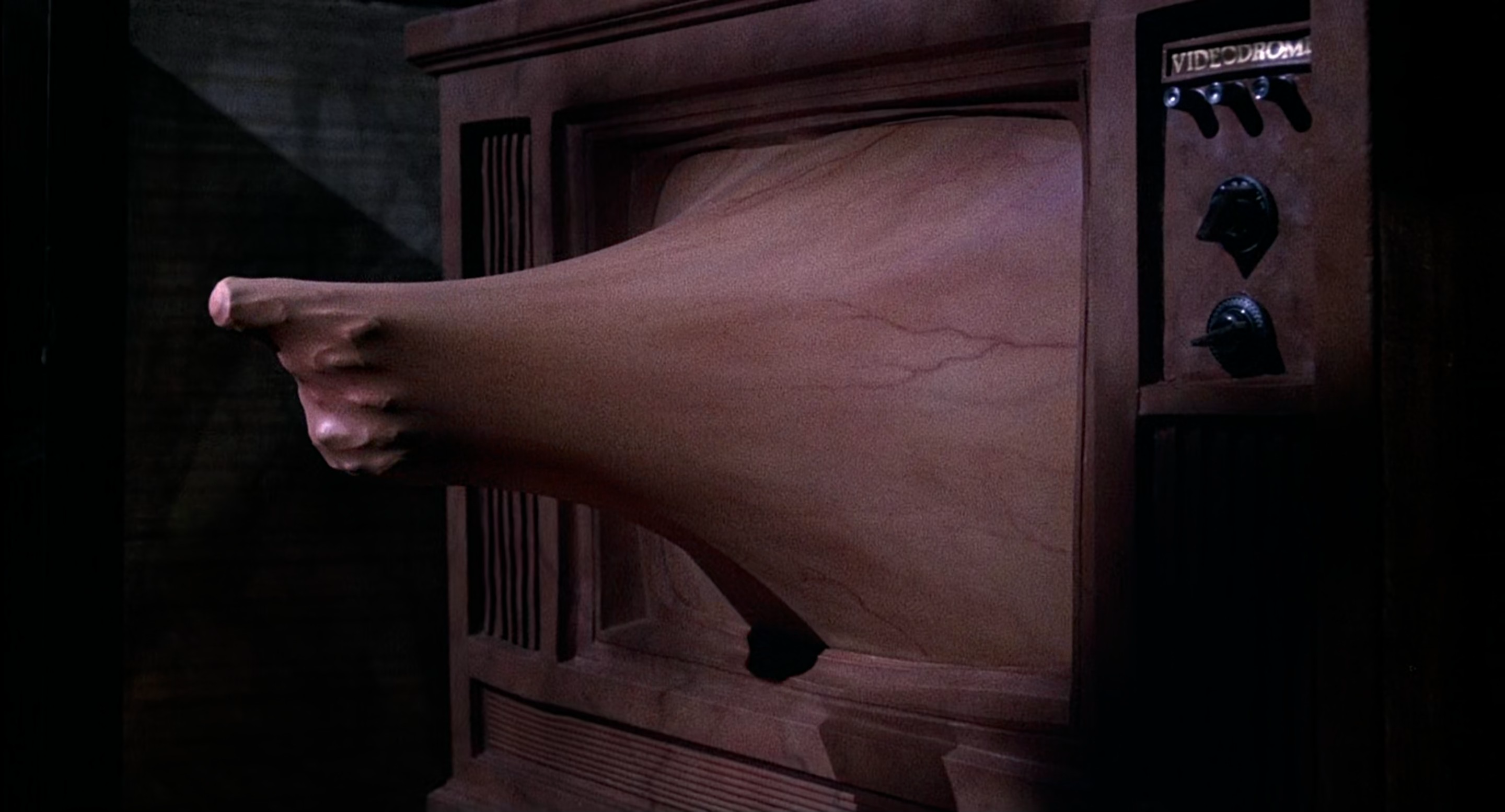

Beyond the raw impact of Cronenberg’s body horror, his navigation of Videodrome’s noir-adjacent narrative of femme fatales and lethal conspiracies also takes on subtler, more foreboding undertones. His camera carefully creeps through sets, anxiously dreading whatever it might discover, and is often accompanied by Howard Shore’s eerie orchestral score gradually incorporating synthesisers into the mix, mirroring the hybridity of Cronenberg’s techno-surrealist imagery. There, we witness televisions become living organisms, breathing in slow, raspy rhythms as their screens bulge outwards and reach for Max. In one of his dreams, he finds himself back in the Videodrome room with Nicki, though this time she is only present as an image on one of these fleshy television sets. She gasps in pleasure as he whips her, before transforming into Masha, one of Max’s senior acquaintances in the porn industry. Later, he discovers that a fleshy cavity has opened in his torso, turning him into the perfect subject for brainwashing as he is now able to absorb whatever political programming is fed to him through VHS tapes.

Just as O’Blivion predicted, that which is artificial has come alive, and life has in turn become artificial. In representing this, Cronenberg’s biotic practical effects are deeply unsettling, robbing characters of their humanity by fusing them with the technology they have become so reliant on, and urging them onto the next step in their synthetic evolution. O’Blivion has already reached that stage by escaping his physical body and becoming one with physical media, and soon enough it is Max’s turn as well to become what the anti-Videodrome faction enigmatically call “the new flesh.”

To Barry Convex, producer of the Videodrome program and staunch moral puritan, television has proven to be little more than a “giant hallucination machine” that will bring the downfall of modern North America, though given his murderous solution he is clearly no less corrupt than his rivals. The eyeglasses company he runs makes for a brilliant formal contrast against O’Blivions worship of screens, as while it seems to offer a clearer, more traditional view of reality, it is little more than a front for much shadier dealings.

Max is just as objectified while under his control as he when is under O’Blivion’s, but such is the nature of this cruel political warfare that aims to wipe humanity clean of its very essence, whether that be in our free will, our imperfections, or our ability to distinguish fact from fantasy. Regardless of who wins, the rest of the world loses, and by the end of Videodrome there is little doubt to be had as to which dystopia will come out on top. Mass media is the weapon in these culture wars, Cronenberg posits, and our minds are the stakes, as disconcertingly frail as our own ailing bodies.

Videodrome is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green