Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 43min

The rapid destruction of civilisation by the fictional, unnamed war in Shame is split into two halves, each mirroring the other in chilling severity. The first part of society to crumble are the homes and lives of its citizens, spelling out apocalyptic horror in almost every shot from the moment bombs start falling. Only when social order has been extinguished can the second seal be broken, twisting the souls of survivors into distorted shadows of their former selves. It is with their total moral defeat that Ingmar Bergman settles an all-encompassing hopelessness over the only war film of his career, taking this study of human violence to its logical, haunting end.

It was only a few months after Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow wrapped production on Hour of the Wolf that they collaborated with Bergman to play another couple tormented by inner and outer demons. Jan and Eva’s minor frustrations at the start of Shame are nothing compared to what awaits them down the road. They are but humble farmers who have retired from careers as violinists, and even as hints of an impending invasion accumulate in tolling church bells, armoured vehicles, and radio broadcasts, they still find time to sit down and speak casually of their futures over lunch. Learning Italian, playing music, having babies – the expectant optimism of their conversation is only vaguely disrupted by Eva’s dig at Jan’s selfishness, which he nevertheless takes in his stride.

The four minutes we spend studying Ullmann’s sensitive face in this unbroken shot makes the emotional whiplash a mere few moments later land with shattering formal impact. Bergman’s frenzied editing of jets flying overhead and exploding bombs drastically accelerates the pacing, as Eva drops to the ground and Jan gazes up in terror. It is at this point in Shame that both embark on an emotional odyssey of confusion, fear, hatred, guilt, and anger, while the contentment we witnessed earlier in the scene becomes little more than a distant dream.

Perhaps their subsequent slog across desolate landscapes of burning buildings, dead bodies, and bombs kicking up dust on the horizon had some cinematic influence over later war films too such as Apocalypse Now and Come and See, as Bergman brings an enormous visual scope to his cheerless narrative. Sven Nykvist’s cinematography is as crisp in its monochrome austerity as ever, panning with the characters across cataclysmic set pieces larger than anything he had shot before, while Bergman strips back dialogue to hold us in the grip of his visual storytelling.

It is in these wordless sequences that entire worlds are built beyond the scope of the immediate plot, revealing lives that were once as vivid as Jan and Eva’s, yet which have been painfully extinguished. Here we witness the true extent of the war’s destruction – the charred husk of church in the distance hosting a small funeral procession for example, and a boat of refugees floating atop an ocean of dead bodies. Even this far away from the mainland, Shame’s disturbing symbolic imagery continues to haunt its survivors.

Bergman’s colossal set pieces are not a departure from the interior lives of his characters though, but rather an extension of their troubled minds, where the stakes for the second part of this battle are waged. Here, a new question is posed – if it takes a nation’s military to topple structures and end lives, then what sort of psychological forces does it take to kill the human spirit? Gaslighting innocent people through scare tactics is one viable method, as we see footage of Eva doctored to make her sound sympathetic to the enemy, thereby eroding her trust in authority. Self-disgust is a powerful weapon too, as former mayor Colonel Jacobi manipulatively offers Eva and her husband protection in exchange for sexual favours. Perhaps the most crushing weapon of all though is the mutual contempt that manifests between lovers, preventing any return to domestic tranquillity even when the immediate danger has faded.

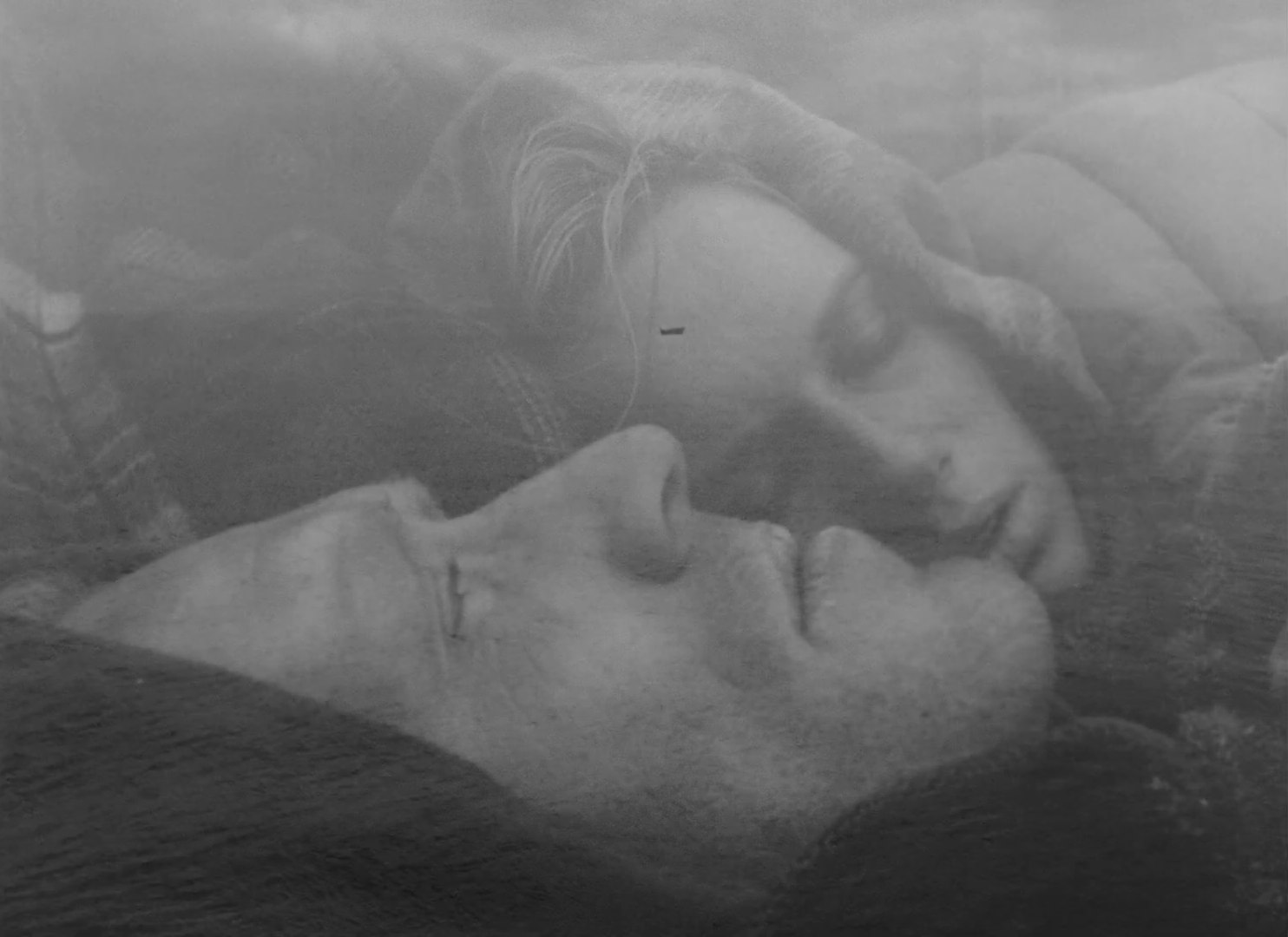

The incredible composition of Jan’s profile obscuring Eva’s face as both rest their heads after the first day of the invasion started might be the last true moment of peace they share in this film. When they finally return to their farm afterwards, no longer is Eva the same calm, strong woman she was before. One day when she discovers Jan weeping, her only acknowledgement of his feelings comes as a short, savage jab – “Cry if you think it helps.” The prospect of having children is now out of the question, and her bright, honest eyes are widened in fear and sorrow.

Perhaps even more shocking is Jan’s transformation from a coward into a ruthless killer, nihilistically participating in the dog-eat-dog world that has risen up around him. Jacobi is the first to suffer a prolonged, painful death at his hands when he fatefully requests the return of a large sum of money, and later when the married couple meets a young soldier on the road, Jan doesn’t hesitate to murder and rob him too.

Where the internal and external violence of Shame intersect most acutely is in the eventual fiery ruin of Jan and Eva’s home, mercilessly set alight by the military for Jan’s refusal to pay up the money that would earn Jacobi his freedom. This daunting set piece simultaneously represents the brutal destruction of everything they have built together over many years, and the easily avoidable consequences of Jan’s stubborn greed – the money that he pretended not to have was hidden in his back pocket all along. The disbelief written across Ullmann’s face upon this reveal might almost be read as fury if it wasn’t so completely drained of emotional energy. Like so many of the greatest war film directors, it is Bergman’s profound ability to draw such profoundly personal stakes from widespread trauma which shape his severe, pensive ruminations. From there, Shame just keeps descending into an irreversible degradation of innocence, love, and compassion, dehumanising the same people we might have once trusted to restore sanity to a broken world.

Shame is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1960s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green