Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, Justin K. Thompson | 2hr 16min

The conventional standard of 3D animation and photorealism has been so entrenched in the movie industry of recent years that it often feels as if mainstream studios such as Disney have hit the ceiling of creativity, prioritising cutting-edge technology over illustrative artistry. Perhaps 2018 audiences didn’t know it at the time, but they were ready for freshly inspired animators to shake up the medium, and so Phil Lord and Christopher Miller stepped up with the vibrantly expressionist Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. All at once, the comic book movie genre was reinvigorated with a meta-modernist spin, Sony Pictures Animation established themselves as a serious competitor to Disney, and audiences were reminded of the artform’s enormous artistic potential.

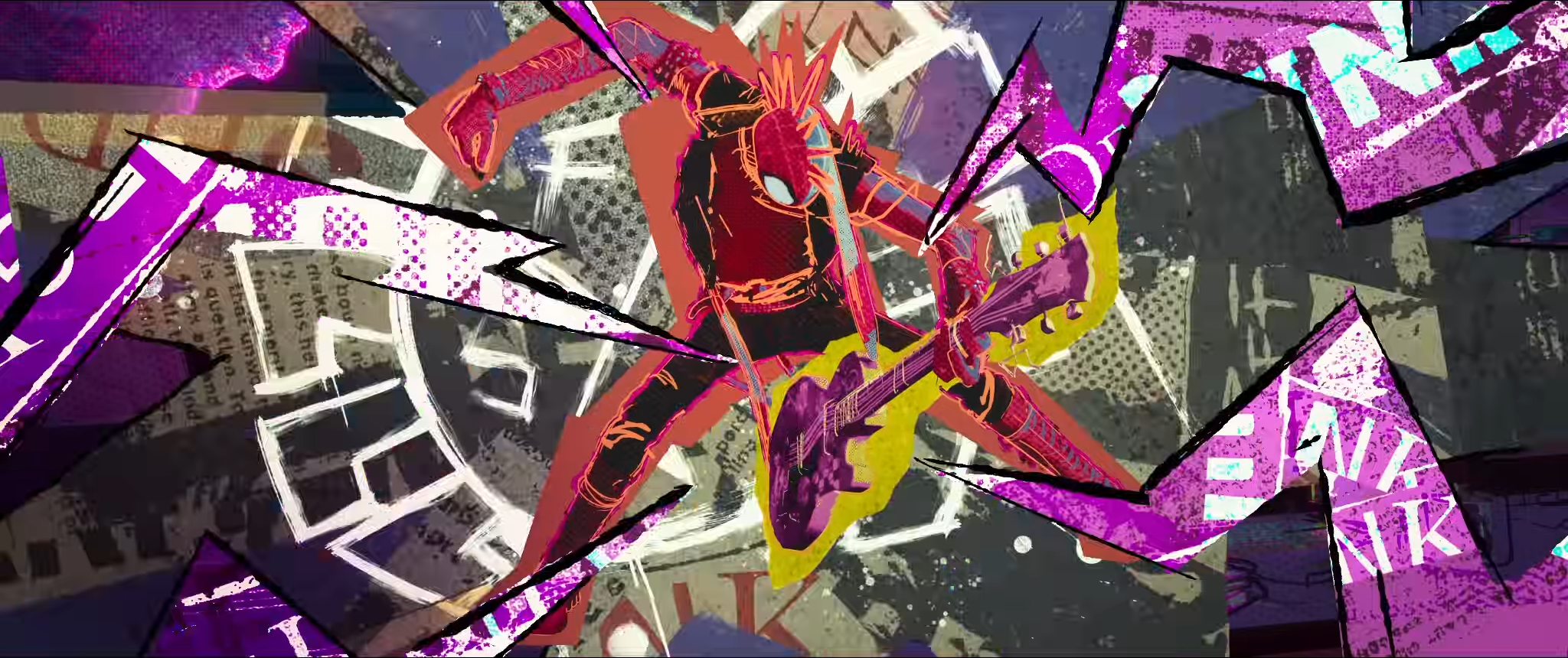

If nothing else, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is confirmation that the success of the first film was no fluke. The fluorescent, Ben-Day dotted New York city that defined that story’s primary setting is largely secondary here to the huge array of alternate Earths we visit, each one defined by its own distinct pop art style. Therein lies the bulk of Lord and Miller’s visual ambition, which may even exceed the Into the Spider-Verse. At its most eccentric, brief diversions within the film adopt the look of Renaissance parchment sketches and stop-motion Lego, while the more significant character of Spider-Punk seems to be made up of moving collages from aggressive rock posters, and Spider-Man 2099 takes on a more neo-futurist composition. When these variations mix in large ensembles, there is a mish-mash effect of assorted frame rates and designs running up against each other – not unlike the small collection of incongruent Spider-Men from the first film, but this time expanding out into entire worlds.

Besides Miles’ New York which is as sumptuous as ever, the greatest aesthetic accomplishment of all these universes clearly sits in Gwen Stacey’s, which appears to shift colours, tones, and backgrounds like impressionistic renderings of her changing moods. Her New York is painted out in pastel watercolours that liquefy around her, and the editing matches this fluidity in match cuts which effortlessly slip through time. During one argument that takes place between her and her father, even the walls of their family home begin to subtly drip around them like wet paint, before brightening into geometric patterns as some hope for their relationship emerges.

If there is anything which binds all these distinct styles together, it is the hyper-kineticism present in their dynamic editing, thrusting us through split screens, slow-motion action, strobe-like montages, and pop-up boxes divulging brief pieces of exposition before disappearing. Gravity also seems to hold little power whenever a Spider-Man variation is around as the camera is constantly finding unorthodox angles unique to their perspectives, clinging sideways to walls and upside-down from towering structures.

It is similarities like these that bind each incarnation of this superhero into a single unified identity, and which in turn becomes the subject of Across the Spider-Verse’s genre deconstruction. Here, they are neatly labelled the ‘canon’, defining every Spider-Man by a common series of events that pushes them towards their destiny, and connecting them to a broader set of archetypes within their own narratives. Where the previous film considered this as a benchmark for new generations of heroes though, questions of free will enter the mix here – perhaps personal suffering does motivate people into creating better worlds, but must it be a prerequisite?

Though the two antagonists presented in Across the Spider-Verse are conflicting in their designs, with one being a comical “villain of the week” and the other a single-minded protector of the multiverse, both serve similar functions in ensuring that Miles meets the tragedy the canon dictates. That one essentially disappears halfway through the film and the other only really enters at this point marks a small formal flaw, but at the same time it is difficult to fully assess the structure of this story given how much it seems to be connected to its upcoming sequel, Beyond the Spider-Verse.

As this film builds to a climax, Lord and Miller do well in pulling one over on the audience with nifty a fake-out edit not unlike the police raid of The Silence of the Lambs,leading into a cliff-hanger which, while tantalising, does not provide any real closure. Even while comparable films like Avengers: Infinity War and The Empire Strikes Back simultaneously set up further sequels while dramatically raising their stakes, they still effectively wrap up their own self-contained plots in a way that Across the Spider-Verse does not. Lord and Miller’s grand plan to dismantle the elevated hero archetype with self-reflexive humour and bombastic animation is evidently not even close to complete at this point. As far as cinematic storytelling goes, this is merely the first half of a much longer film, endeavouring to break through the same narrative conventions that its predestined characters are fighting against.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2020s Decade (so far) – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Composers of the Last Decade – Scene by Green