Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 28min

Symbolic contemplations of spiritual isolation, broken identities, and human mortality have long instilled an existential unease in Ingmar Bergman’s films, and yet as we trace back the steps of one mentally unwell painter leading up to his death in Hour of the Wolf, it becomes clear that none have come this close to outright psychological horror. The demons that pour from Johan’s mind onto blank canvases are almost Lovecraftian in their eerie, abstract creation – he is haunted by an old woman whose face comes off with her hat and the terrifying Bird Man, along with the meat-eaters, the schoolmaster, and the cast-iron, cackling women. That they are simply figments of his tortured imagination makes them no less dangerous, or any less real. After all, they are also fully visible to his wife, Alma. Her recount of Johan’s final days may not offer hard answers to the many lingering mysteries left in his wake, and yet in her abiding love, compassionate understanding can be found.

It is surely intentional on Bergman’s part that the name Alma was used in his previous film, Persona, similarly characterising a woman who acts as the mouthpiece for an interdependent couple. Where Liv Ullman played the mute Elisabet there though, she openly invites the audience into the film as the Alma here, directing her narration directly to the camera. She is nothing less than astounding, following up on Persona with another viscerally interior performance, now torn between complete helplessness and determined support for her husband. It is her point-of-view that Bergman frequently takes in Hour of the Wolf’s visuals and narrative, often mirroring the fearful delusion embodied by her co-star, Max von Sydow. Much like Persona, this is a study of dual identities blending in isolation, only with its focus shifted to lovers rather than acquaintances.

Besides Alma, Johan, and his evil spirits, there is another presence on this small island where they reside. Visions of his ex-lover Veronica disturb him with small talk and seductions, lulling him into dreams of the past which in turn add to the mounting shame his demons feed on. The letter she reads to him does not have an explicit sender, but given its menacing, apocalyptic undertones, it is safe to assume their identity.

“You don’t see us, but we see you. The worst can happen. Dreams can be revealed. The end is near. The wells will run dry, and other liquids will moisten your white loins. So it has been decided.”

Neither is it terribly difficult to guess the conspiratorial truth that lurks behind the guises of Johan and Alma’s bizarre neighbours who frequently drop by without notice. One of them, Baron von Merkens, appears kind enough to extend an invitation to his castle for a large dinner party, though anyone with the vaguest understanding of Gothic storytelling conventions will know to take this as an ominous warning.

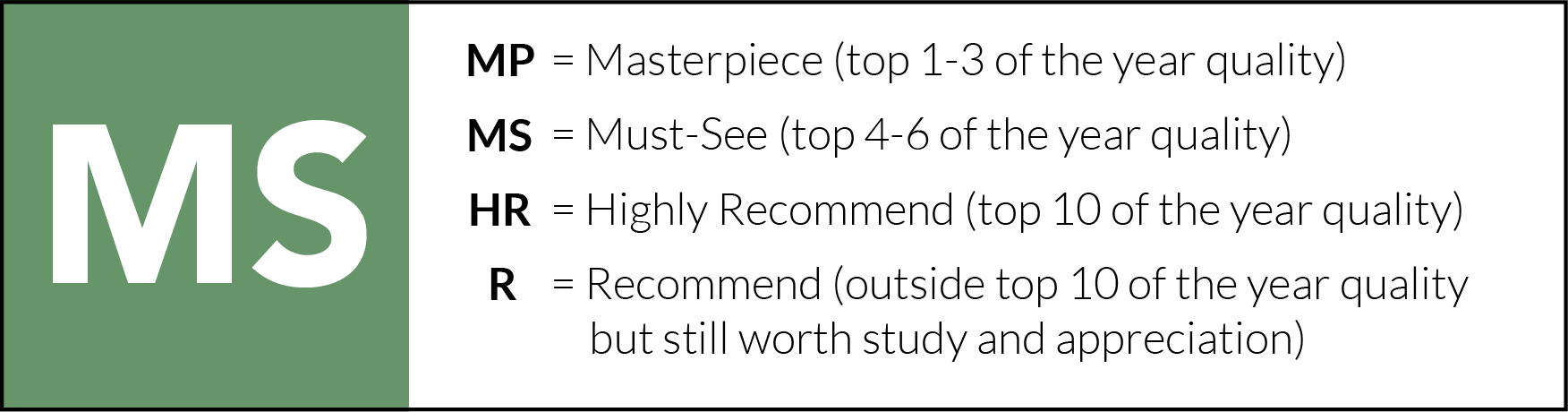

As the guests settle at the Baron’s large table, Bergman’s camera rapidly circles them in a dizzying 360 shot, before manically whipping between POV close-ups of them talking right down the lens as their conversations bounce across the room. Afterwards, one of the men performs a candle-lit puppet show, though Alma is far more preoccupied by his leering face staring down at her, partially concealed by a shadow crossing his mouth like a wide, dark smile. The Baroness’ reveal that she has hung Johan’s painting of Veronica directly in front of her bed ends the evening on a note of uncomfortable humiliation, and leaves behind a lingering dread as they return home.

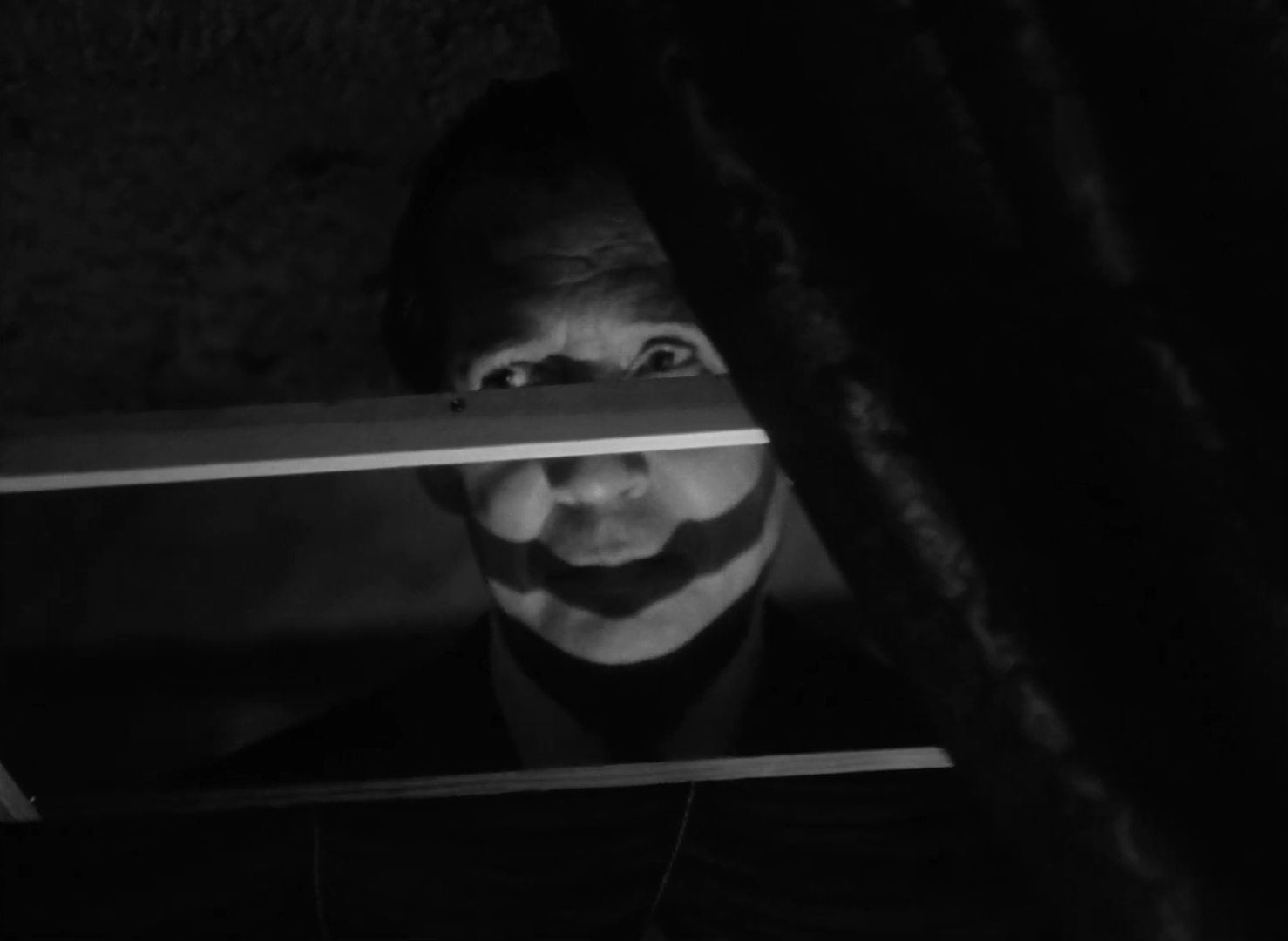

Bergman’s framing of his entire ensemble is almost always confronting, but those intimate scenes consisting solely of Johan and Alma are often just as sensitively composed. The camera’s deep focus intensely studies the insecurity that crosses von Sydow and Ullmann’s faces in breathtaking arrangements, and as Johan speaks of that dark hour every night “when nightmares come to us,” his tormented expression is lit but nothing more than a single match. Outside too, it similarly becomes apparent that this couple has built their house on uneven foundations, with the steep, rocky hills of this rural island throwing off the balance of Bergman’s exterior shots.

While much of this story takes place through Alma’s flashbacks and her perusal of Johan’s diaries, Hour of the Wolf continues to sink us another layer deeper via his personal, distorted memories of one fated summer vacation. His violent struggle and murder of a young boy on the edge of a cliff is brightly over-exposed, separating us from reality and forcing us to question how much of this scene is merely symbolic, while in place of diegetic sound we simply find Lars Johan Werle’s unsettling, dissonant score. Mouths open, but no screams can be heard, cruelly stifling the painter’s raw expressions of agony.

Perhaps this boy was yet another demon that resided inside Johan, who even after being killed and thrown into the ocean simply floated back to the surface. Maybe the scene is closer to a representation of truth than we might like to believe, revealing another dimension of darkness to the painter’s subconscious. Either way, it has left a guilt within him which cannot be killed, and given the long dissolve which transitions from this dream back to Alma’s horrified face, we can clearly see that it haunts her just as much.

When these spirits inevitably re-enter at the deepest point of Johan’s breakdown, all pretensions of civility are dropped, and that vague unease manifests as phantasmagorical terror. Bergman had already proven himself a talented surrealist in films like Wild Strawberries, but the aberrant horror he crafts in images of the Bird Man revealing his wings, the Baron walking up walls, and the old woman finally ripping her face off is downright chilling. After powdering Johan’s face and dressing him up like a cadaver prepared for the grave, these mischievous figures push him to his final stop – Veronica’s naked, dead body. He runs his hand over her skin from top to bottom, perversely drawn to her lifeless figure, and even as she starts cackling, he tries to kiss her. Her head tilts back into the light, casting harsh light and shadows across her sadistic face, and then all of a sudden, we realise the other demons are watching too.

The wide shot of this diabolic ensemble cackling at the camera in twisted positions makes for a frighteningly morbid composition, with two peeking around corners, another perched in a window like a bird, and another still lifting her dress in vicious mockery. Johan, with his make-up now smeared across his face, can only resign in defeat and recognition of his mutilated ego.

“I thank you… that the limit has finally been transgressed. The mirror has been shattered. But what do the shards reflect? Can you tell me that?”

His lips continue to move yet no sound emerges, much like in his murderous dream, and again later when he meets his end at their hands in the woods. Bergman’s montage editing throughout his death is fast and violent, weaving in close-ups of ravens, eyes, and blood, and Alma is there to witness it all. In pensive reflection, she returns to a passing thought that crossed her mind earlier in the film, which might answer why these demons were visible to her as well.

“Isn’t it true that when a woman has lived a long time with a man… isn’t it true that she finally becomes like that man? Since she loves him, and tries to think like him, and sees things like him. It’s said that it can change a person. Is that why I began seeing those spirits? Or were they there regardless?”

To extend that line of questioning even further, did those demons truly die with Johan, or do they now simply live on in her mind? Through this psychological blending of identities, Hour of the Wolf warps our most intimate attachments into our greatest vulnerabilities, denying us even the sanctuary of Alma and Johan’s love to fall back on as a source of security.

At the same time, it doesn’t seem as if Bergman would have it any other way, especially considering the selfish contempt between couples which is present in so many of his films, and yet which is mostly absent here. Alma is a troubled woman, but she may also be one of his most purely compassionate characters he has ever written, surrendering her own stable mind to ease her husband’s heavy mental load. Even when faced with the existential horror which Bergman so surreally instils in Hour of the Wolf, there is still grace to be found in that hopeless, sacrificial love.

Hour of the Wolf is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1960s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green