Masaki Kobayashi | 2hr 13min

The corruption of cultural tradition in Harakiri has not merely unfolded through passive spiritual negligence, but rather arises from its own historical foundations, and driven by the flawed, selfish humanity hiding behind it. The respected Iyi Clan would much rather shift the blame onto those impoverished men who enter their estate, claiming their intention to commit honourable suicide by seppuku, yet secretly wishing to be sent away with alms in hand. To these samurai masters, it is an exploitation of ancient customs by peasants who have little respect for anything beyond their own immediate existence, and thereby casting suspicion on any visitors seemingly searching for a respectable death. The solution is simple but cruel – force these beggars to follow through on their promise and disembowel themselves in humiliation.

Masaki Kobayashi was well positioned in 1962 to direct a samurai film as spectacularly pessimistic as this, having just come off the back of his anti-war Human Condition trilogy which bears a similarly cynical view of authority. Tatsuya Nakadai returns as the lead here as well, but the mental resolution he carried in his previous character manifests with far greater hostility in the vengeful Tsugumo Hanshirō. Though only thirty years old during the time of filming, Nakadai is convincingly aged up as the middle-aged rōnin who refuses to let his bitter anger die with him. The sudden loss of his son-in-law, Motome, directly led to the death of his grandson Kingo, as well as his daughter Miho, and it is clear enough in his eyes that the blame lies squarely on those who coerced him into a reluctant suicide.

Set at the dawn of the Edo period in the 17th century, Harakiri is dense with cultural details which establish it as a profoundly rich Japanese text, though at the same time Kobayashi is incredibly economical with his storytelling. The warning that Saitō, the Iyi clan’s senior counsellor, delivers to Hanshirō against lying about one’s intent to commit seppuku is delivered through an extended flashback, yet this becomes more than just a cautionary tale. The man in this recount is none other than Motome, whose bluff is called from the start and is thus condemned to slice open his belly with his own sword. His switching out of real steel with blunt bamboo blades gruesomely comes back to bite him at this point, denying him a quick, dignified death, though it is the callous masters feigning ignorance to this detail who are the most morally tainted of all.

Stylistic comparisons may be fairly drawn in these violent scenes to Akira Kurosawa’s own kinetic action, as Kobayashi designs each wide shot with careful attention to the detail of his stunning environments. Most of these take place within the confines of the Iyi clan’s palace, visually representing centuries of tradition through exquisite displays of Japanese architecture, though as Hanshirō moves into his version of events in a Rashomon-style perspective switch, Kobayashi relishes the expansion of his narrative’s scope. A cemetery of crowded headstones, a towering bamboo forest, and hills of long grass form picturesque settings through the lead-up to Hanshirō’s confrontation with an Iyi master, while the wind gracefully blows dust around them in dynamic counterpoint to their sharp movements.

Kobayashi’s obstruction of many of these frames do well to set him apart from Kurosawa though, and even more distinct to his style are those canted angles which previously appeared in The Human Condition, and are once again used here as signifiers of chaos. The balance of the entire world is thrown off in these compositions, inducing anxious terror as Motome is forced to slice his own belly open, and awe as Hanshirō and his opponents raise their swords against each other. Crash zooms also bring jolts of kinetic energy to these scenes, disrupting static shots to narrow in on dramatic narrative developments, and originating a creative visual technique that would be popularised in many Asian action films in decades to come.

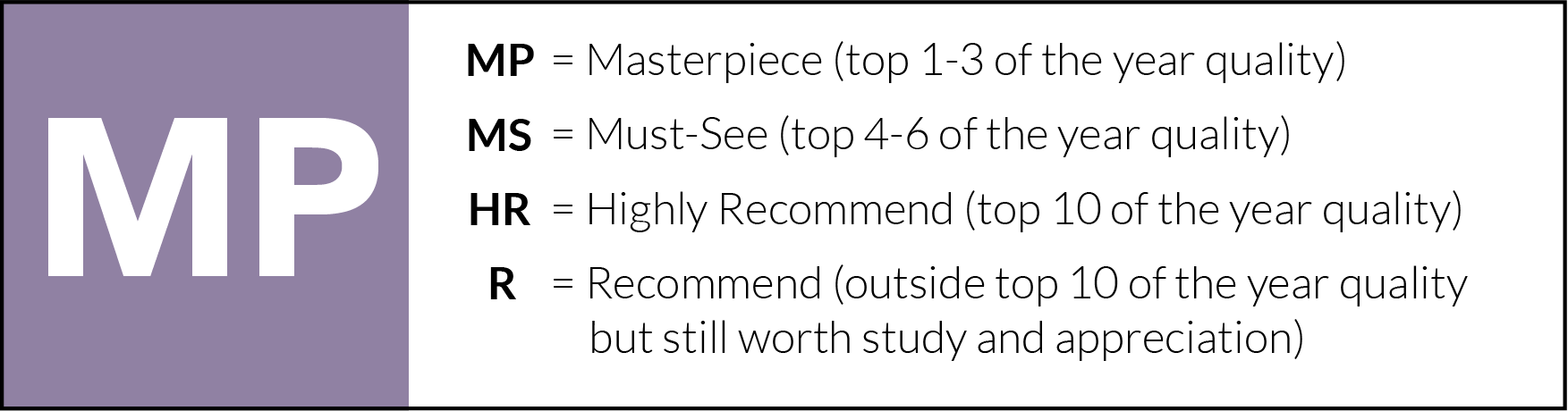

Emphasising this anarchic imagery even further is the contrast it strikes next to the rest of Kobayashi’s immaculate staging, ordering characters in rigorous formations throughout the elaborate palace. In the courtyard where Hanshirō sits to perform his harakiri, armoured men evenly line the edges holding spears, while Saitō looks down from a raised platform upon the vulnerable rōnin. When the camera moves, it often dollies in straight, unyielding lines, traversing a world defined by tradition and structure, yet which cannot stand up to the corrupt impulses of man. The minimalist score consisting of an aggressively strummed biwa captures both ends of the spectrum too, as composer Tōru Takemitsu plays atonal fragments of music on this thousand-year-old Japanese instrument like an ancient outcry of fresh, wounded anger.

The source of Hanshirō’s emotional pain is abundantly clear from his backstory, though the cynical new philosophy he has drawn from it is most succinctly captured in a single, accusatory line.

“This thing we call samurai honour is ultimately nothing but a facade.”

For men who claim to be models of respect, righteousness, and consistency, their indirect murder of Japan’s most underprivileged civilians is antithetical to everything they stand for. They place little value in anything that doesn’t prop up their own bloated egos, and now as Hanshirō lashes out and engages hordes of these samurai in combat, that hypocrisy is fully exposed. He is a far more talented swordsman than any of these pompous men, cutting down eight of them before committing harakiri. Though the act is filled with deep bitterness rather than peaceful reverence, this is not a significant perversion of tradition – after all, can something truly be degraded if those in control had already spoiled it long ago, turning it from a sacred ritual into a cruel punishment?

As the Iyi samurais begin to realise that they are losing the battle, they turn in their swords for guns, dispensing with their customs the moment they prove inconvenient. The ancient suit of armour that Kobayashi returns to several times throughout the film becomes symbolic of that empty glory here too, as Hanshirō disdainfully uses it as a shield before throwing it to the ground like a piece of scrap metal.

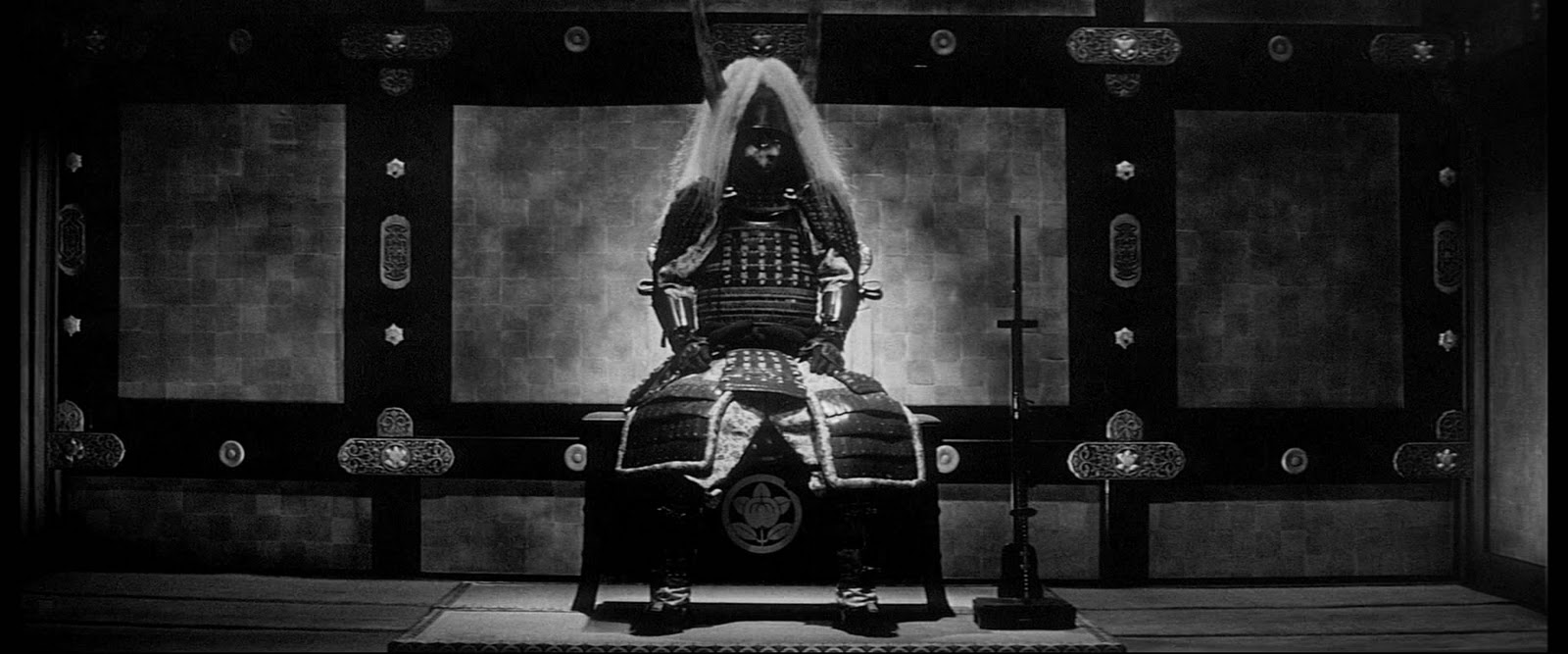

Perhaps the most damning evidence of samurai culture’s false honour though arrives in Kobayashi’s epilogue. Before coming to the Iyi estate, Hanshirō defeated the three masters who coerced Motome into suicide, taking their top knots and forcing them to hide in shame. With their façade of respectability gone, they are now little more than a burden on the clan’s reputation, and so arrangements are made for them to commit seppuku. The official journal entries which open and close the film are saturated with stifled shame, attempting to cover up the clan’s disgrace by recording Motome and Hanshirō’s deaths as harakiri, and the three masters’ demises as mere illnesses. The clan’s surviving samurais may tidy the palace, re-erect the armour, and dispose of the three severed top knots, yet their hearts continue to rot in guilty silence, condemned to lie in graves of obscene spiritual corruption that they have spent centuries digging for themselves.

Harakiri is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1960s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green