Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 25min

Through the twenty years of Ingmar Bergman’s career leading up to his crowning achievement Persona, his long running fascinations with the human face had manifested in some of the art form’s finest close-ups. It is “the great subject of cinema,” he believed. “Everything is there.” He didn’t need David Lean’s extraordinary panoramas or Michelangelo Antonioni’s modern architecture, though he certainly demonstrated a fine control over both visual devices whenever a scene called for it. To him, faces were landscapes on their own, with the potential to be shot in an unlimited number of angles, lighting setups, and arrangements within ensembles – and that isn’t even considering yet the incredible facial expressions reliably delivered by his troupe of recurring actors. In profile shots, the curves of the face become valleys and mountains, while front-on portraits might be partially hidden by shadows or visual obstructions.

As such, there is an inherent tension between any character’s outward communication and internal emotions in a Bergman film. Not necessarily at odds with each other, but at least working in conjunction to create a mask of some kind. One which Carl Jung might describe as “designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and on the other to conceal the true nature of the individual.” Or to put it even more simply, a persona.

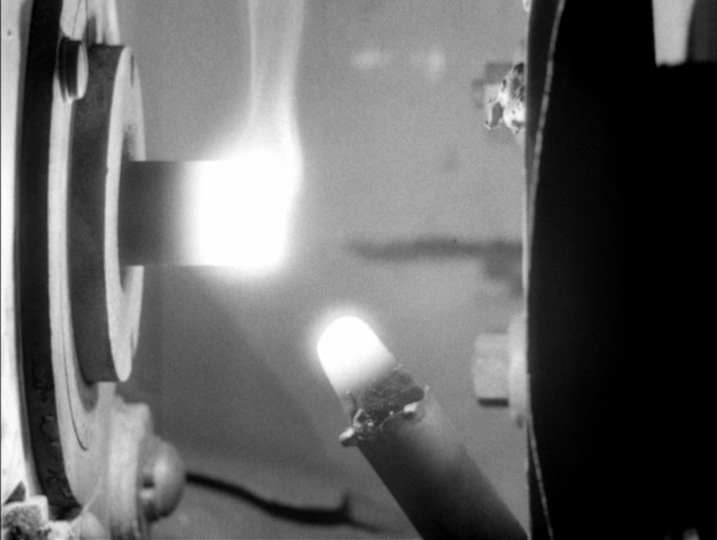

Therein lies the case for why this film may stand as the finest formal synthesis of Bergman’s intimate visual style and his deeply psychological subject matter, examining the perplexing duality which simultaneously defines humans as social beings and distinct individuals. All abstract truths conceived in one’s mind must be filtered through some sensory expression to reach the outer world, and Bergman does not discount his own film from that inevitable distortion. The raw materials of cinema itself become integral to Persona’s very form, opening and closing with montages of film reels, flickering lights, a penis, a cartoon, a silent comedy sketch, and a dying sheep, among other images. Even the very final shot of the film after Bergman’s camera pulls back to reveal his crew shows the film reel running out, and the incandescent arc lamp of a projector slowly dimming, signifying the end.

Much like everything else we witness in this film, these are but mere representations of reality, only possible through illusions of light produced by machines. And yet like the young boy we see at the start reaching out towards a giant screen featuring blurred images of Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson’s faces, we too might find ourselves suspending our disbelief during Persona, convincing ourselves on some subconscious level what we are watching is not art, but truth.

Perhaps it is a similar recognition of this artifice which prompts theatre actress Elisabet Vogler to become voluntarily mute as she stands onstage, simultaneously rejecting both artistic and verbal forms of expression, and setting off the events of the film. To her nurse Alma, Elisabet’s mental strength to wilfully remain silent inspires great admiration, though the head doctor describes her philosophy from a far more nuanced, understanding perspective.

“The hopeless dream of being – not seeming, but being. At every waking moment, alert. The gulf between what you are with others, and what you are alone. The vertigo and the constant hunger to be exposed, to be seen through, perhaps even wiped out. Every inflection and every gesture a lie, every smile a grimace. Suicide? No, too vulgar. But you can refuse to move, refuse to talk, so that you don’t have to lie. You can shut yourself in. Then you needn’t play any parts or make wrong gestures.”

Here lies the key to unlocking many of Persona’s confounding mysteries, moving us closer to the core of one character who conceals her identity with silence, and another who conceals her own with speech. It is one of the finest monologues that Bergman has penned, but it also takes a turn halfway through as the doctor begins to apply pressure to Elisabet’s belief, questioning her methods to separate herself from the world’s superficial facades.

“But reality is diabolical. Your hiding place isn’t watertight. Life trickles in from the outside, and you’re forced to react. No one asks if it is true or false, if you’re genuine or just a sham. Such things matter only in the theatre, and hardly there either. I understand why you don’t speak, why you don’t move, why you’ve created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as you’ve left your other parts one by one.”

With this diagnosis, the remedy becomes apparent – a short stay for both Elisabet and Alma at the doctor’s summer estate. Like so many other Bergman films, his home island of Fårö plays host to this retreat, isolating the two women on beautiful, stony coastlines surrounded by the Baltic Sea.

The dynamic contrast already set between Alma’s endless talking about her life and Elisabet’s patient listening continues here, drawing formal divisions in their characterisations as a submissive, emotional woman and her more assertive, rational counterpart. At the same time, there is also a subtle blending of the two which begins to take place. As Alma recounts a memory of sunbathing nude with her friend, making love with two strangers who approach them, and cheating on her partner, she also confesses a mental guilt which directly conflicts with her physical actions. “Is it possible to be one and the same person at the very same time – I mean, two people?” she wonders aloud, considering both halves of her mind as separate beings.

Through Bergman’s blocking of their faces, this relationship continues to manifest in visual compositions he had played with many times before, specifically that which half-obscures one face with another in a representation of symbiotic duality. Not only is Persona his greatest stylistic accomplishment to date, but his cinematographer Sven Nykvist too deserves a great deal of credit for his camera’s sensitivity to the delicate movements and expressions of these actresses.

When Elisabet enters Alma’s bedroom one night like a spectre, there is a surreal ethereality to the soft wash illuminating their slow, strange embrace, letting them caress each other’s faces and hypnotically gaze right at the camera. Later as they bring their heads together and look downwards, Bergman shrouds them in darkness against a white background, tracing the outlines of their intersecting, virtually indistinguishable profiles. While the emphasis on Elisabet’s face is her shrewd, perceptive eyes, only Alma’s mouth is visible, declaring that “I’ll never be like you. I change all the time. You can do what you want. You won’t get to me.” Once again though, her words are telling a different story to the corresponding reciprocals being depicted onscreen. One is of the head, the other is of the heart, and both might as well be two parts of a single, indivisible woman.

Bergman could not have cast two more suitable actors for these roles either, with both Andersson and Ullmann bearing visual similarities, yet expressing totally inverse personalities. Andersson brings a spontaneous vivacity to Alma’s lengthy monologues throughout Persona, speaking whatever thoughts come to her mind, while initially staged in the foreground of Bergman’s frame as the primary subject of our attention. Meanwhile, Ullmann often sits behind her, watching with an impassive face that refuses to reveal even the slightest passing thought. She may have been late to joining Bergman’s company of regular actors that Andersson had already been part of for years, but in time she would prove herself be among his most integral collaborators, starting with her tremendously silent performance here.

The chemistry between both Andersson and Ullmann only continues to grow more complex as the well-defined dynamic between them starts to break down. When Elisabet first speaks off-screen and encourages a tired Alma to go to bed, the nurse sits up in confusion, not quite believing what she heard. Rather than accepting that her patient has actually spoken, she simply repeats her words, as if verbalising an inner voice. Later when she discovers during their stay that her private life has in fact been the subject of Elisabet’s own supercilious study, the balance of power flips entirely. The observer has become the observed – the last place she wants to be. Acting out of spite for the first time, Alma leaves a shard of broken glass in the open for Elisabet to cut herself on. When she does, the silent eye contact they both share from a distance is full of mutual, contemptuous understanding. This island has turned into a battlefield of identities.

At this point in Persona, just as the status quo has been disrupted, Bergman rips us from his story and back into our own heads. The film reel burns, as if unable to sustain the disturbance that has taken place, and another montage of seemingly random images plays out. In some ways, the formal experimentation Bergman is carrying out here isn’t terribly different to the self-reflexive diversions from conventional narratives that Jean-Luc Godard was also exploring in the 1960s, but the purpose it serves in Persona is far more rooted in Bergman’s own cerebral curiosities. As his characters gradually transcend the limiting identities they have chosen for themselves, so too does his film break down its own façade of truth. When we do eventually make a return to the main story, there is no simple reversion to how it was before. Alma has turned in her white attire for Elisabet’s black, and the tension between them has fully manifested in an outright tangle of personas.

Seeking to draw out a raw, emotional reaction from the composed Elisabet, Alma pushes her to the brink of her patience in a physical confrontation. The threat of boiling water provokes a scream of fear, emerging from a place of honest emotion she has suppressed, and which Alma thrives on – “No, don’t!”. Conversely, the arrival of Elisabet’s husband on the island elusively switches out these women in the other direction, with the visiting man approaching Alma instead of his wife. Bergman’s deep focus blocking once again lifts off in this scene, bringing Andersson and Gunnar Björnstrand’s faces together in sweet reconciliation over past misgivings, as Ullmann’s face imposes itself as a silent, detached presence. Whatever her conflicts have been with her husband, it is not her silence which heals old wounds, but rather Alma’s warmth and connection. Her words from a few scenes prior about the importance of such affectionate openness begin to make even more sense here.

“Is it really so important not to lie, to tell the truth, to speak in a genuine tone of voice? Can a person really live without babbling away, without lying and making up excuses and evading things? Isn’t it better to just let yourself be silly and sloppy and dishonest? Maybe a person gets better by just letting herself be who she is.”

Still, how long can Alma really keep up this act of being a kinder, more considerate Elisabet? “I’m cold and rotten and indifferent. It’s all just sham and lies,” she cries in the man’s tight embrace, just as Bergman pans his camera to the side to reveal a daunting, front-on close-up of Elisabet. In her silent gaze that stares right down the lens, we see these same insecurities manifested as introspection, rather than the outward expression native to Alma’s personality.

At this point, deeper truths about both women and their ever-shifting traits begin to unravel quickly, building to a monologue that plays out twice in a row and pays off on the dual patterns woven tightly into the film’s structure. Alma may be the one who is delivering it, and yet the second-person perspective she speaks from pins the anecdote squarely on Elisabet, verbalising the mute woman’s unspoken thoughts. In this moment, the psychoanalysis which Elisabet had tried turning on the nurse now reverts back to the patient, as Bergman interrogates another false persona adopted by countless women in society – the image of the warm, caring mother. Like many of the characters she has played during her career as an actress, this is just another role she felt she must perform, composing herself with dignified grace while internally torn apart by fear and repulsion.

The first time Bergman plays out this monologue, it is Elisabet’s face which we hang on, its left side cloaked entirely in shadow as she listens in subdued shame. When it comes to an end, a sudden, atonal bang on the piano throws us back in time by a few minutes, and repeats the exact same scene in the mirrored reverse shot. We sit now with Alma as she speaks, her face tightened in attentive focus, and its right side covered in darkness. The distinction of whose story is really being told barely matters at this point – like the two halves of the human brain, we are simply given conflicting perspectives of a single experience, visually expressed through the spliced close-ups of the left and right sides of their faces.

Even by Bergman’s standards, this is unusually experimental filmmaking, though this profound interrogation of human duality asks for nothing less than intellectual patience. When it is time to pack up and leave the estate, there is notably one less woman in the household – has Alma’s decisive rejection of Elisabet pushed the manifestation of her insecurities deeper into her subconscious? Has she absorbed that alter ego into her own personality, and emerged a more balanced being? Or is Alma in fact the figment of Elisabet’s mind that has taken over her life, as we saw with her and Björnstrand’s romance?

The following montage of Elisabet on stages and sets doesn’t quiet help in any search for answers, but it does serve to remind us as Persona comes to its obscure end that these characters have always been little more than artificial constructs, holding no inner lives other than what Bergman instils in them. His film is both deceitful in its purposeful manipulations, but also intricately designed to evoke truths through bold, symbolic expressions, fully recognising the impossible task of creating any pure representation of reality. With the ubiquity of such pointed polarity, Bergman reaches deep into our psyches and exposes our greatest internal paradoxes, creating an avant-garde masterwork that is as entrancingly elusive as it is invasively intimate.

Persona is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1960s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green

Glad you’ve mentioned the idea that Alma and Elizabet might be the same person

However, who do you think is the “original”? Who spawned from whom, and to what end?

It may not be so much that one spawned from the other, than that they are both equal parts of a whole. Maybe neither of them are the original, or maybe both are. Bergman hints in both directions, so I don’t think it can easily be explained.

Considering that, there may even be a “third” somewhere offscreen.