Robert Bresson | 1hr 16min

For men like Michel who deem themselves ‘Übermensch’, there is no need for feelings of guilt. This is merely an emotional hindrance for people who bind themselves to traditional moral values. There is a special class of humans, he reasons, “gifted with intelligence, talent or even genius,” and thus “should be free to disobey laws in certain cases.” If he truly is a being independent of society norms, his petty theft should be excusable. Where then do these feelings of shame come from?

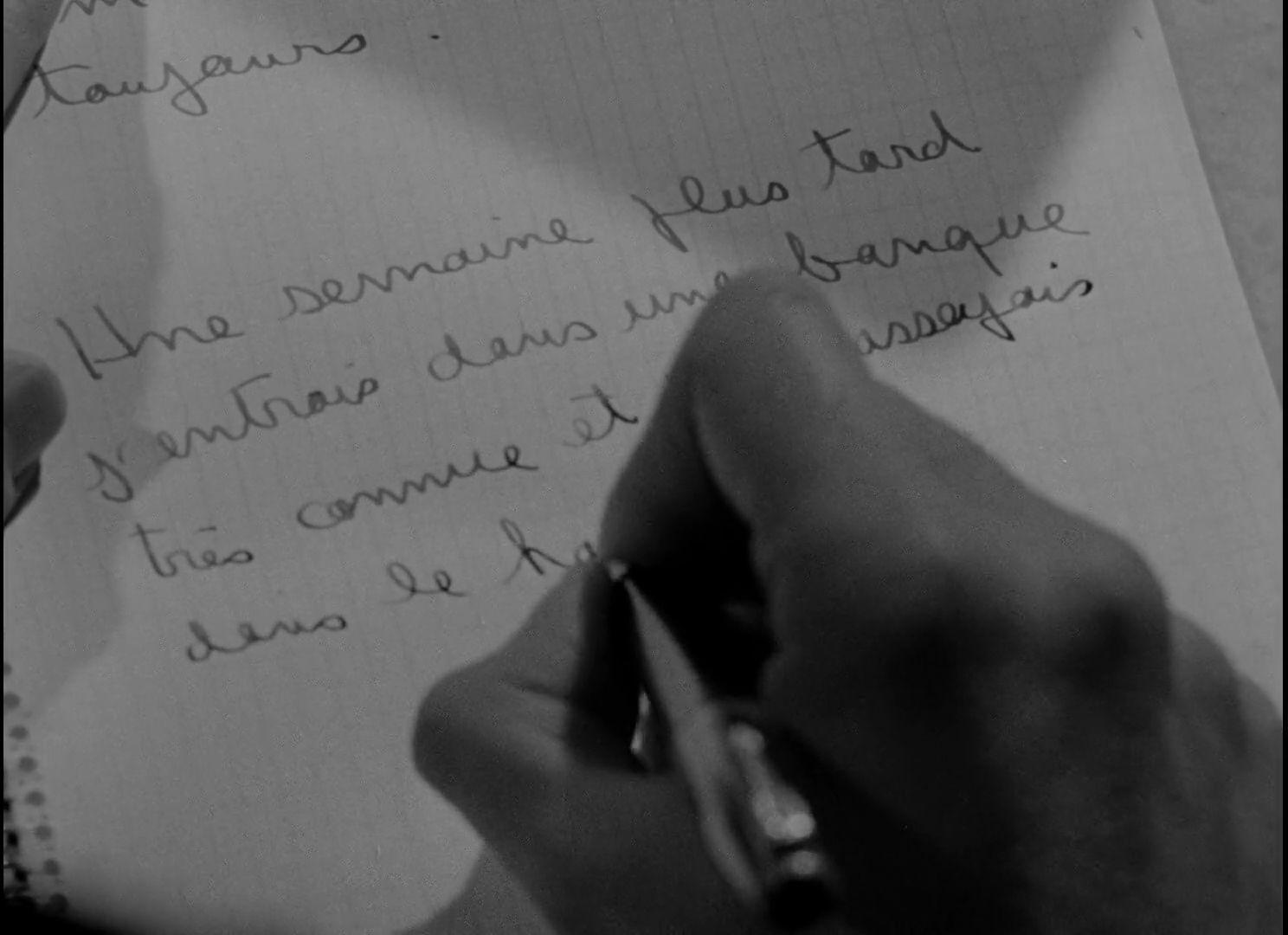

To understand the heart of a Robert Bresson character such as Michel, one must look beyond their outward displays of emotion – or lack thereof. He is not a filmmaker terribly interested in sentiment, and so even in the opening text of Pickpocket he is adamant that this is not a thriller, which would seek to excite and tantalise audiences. Were it in the hands of a Hollywood director, perhaps it might have been, with a fatalistic voiceover spinning poetic metaphors and a visual style running thick with shadows. As it is, this is a drama of subtle internality, employing non-professional actors with expressionless faces to become blank canvases of Bresson’s unembellished vision.

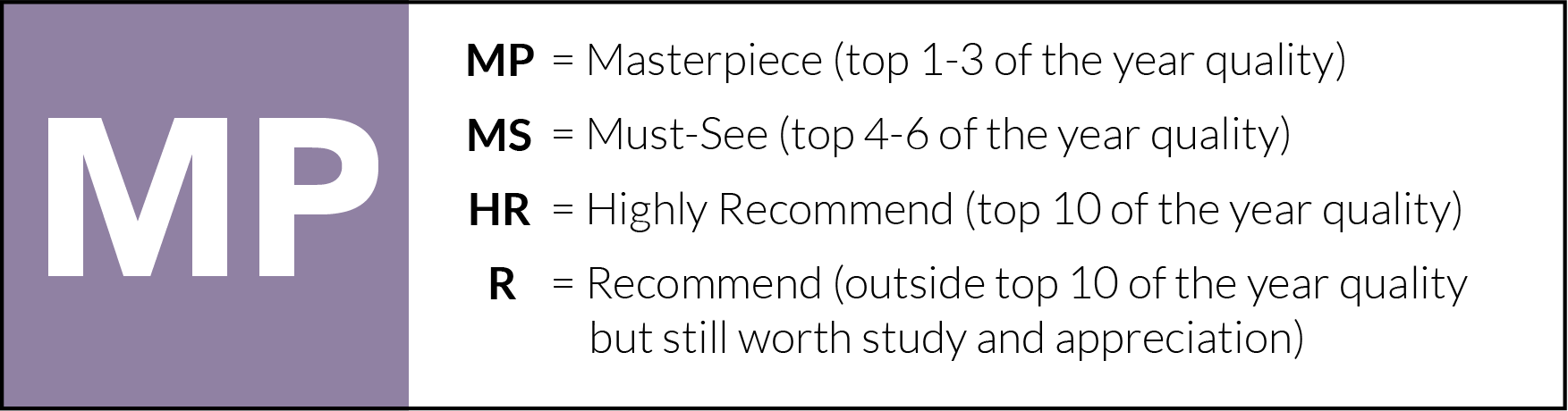

Martin LaSalle fits this mould perfectly as the unblinking Michel, making a film debut which ironically earns him praise for his utter normality. There is nothing exceptional about his appearance, making it easy for him to blend into crowds and steal from strangers. Bresson even refrains from offering him any close-ups which might pick up on stray hints of emotion, and instead turns his camera’s intensive focus towards Michel’s primary tools for work – his hands. After all, it is not his speech or face which opens the clearest window into his mind, but his writing, chronicling his innermost thoughts in private diary entries.

“I know those who’ve done these things usually keep quiet, and those who talk haven’t done them. Yet I have done them.”

These are the words which open Pickpocket, spoken over the first of many shots which narrow in on Michel’s hand putting his musings down in a notebook. Bresson would influence Paul Schrader in many ways, but it is this formal use of voiceover which would so crucially form the basis of his introspective character studies, from Taxi Driver to First Reformed. Much like Travis Bickle and Reverend Toller, Michel’s inner monologue is our primary companion through Pickpocket, leading us into a mind which has grown bored with modern society. He does not turn to theft out of poverty, but is simply motivated by a selfish desire for excitement in his wandering, purposeless existence. That it also cures him of the deep disconnection he feels with the world is a bonus. The power to affect the lives of others is literally in his hands.

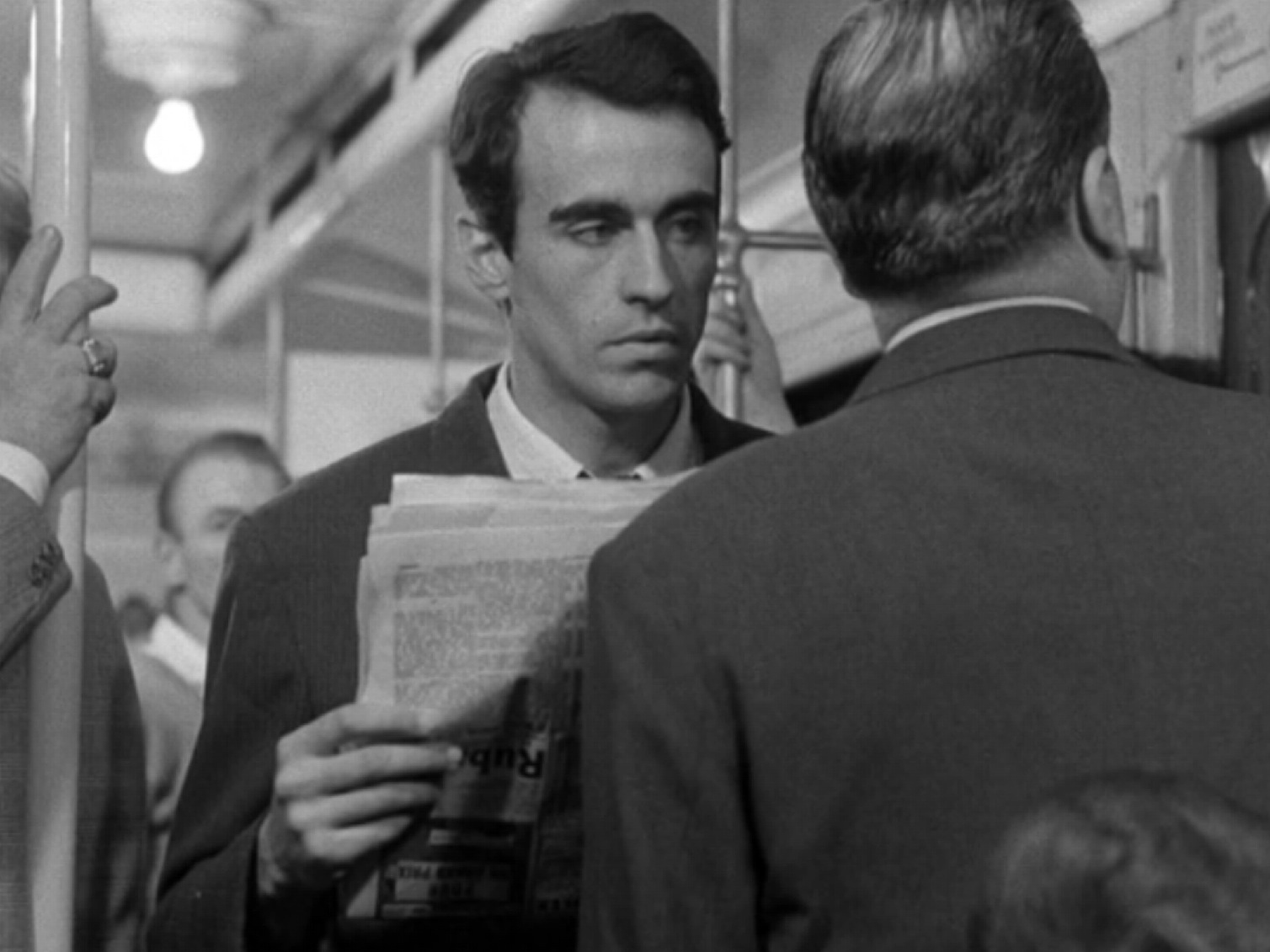

The sensitivity that is absent on the faces of Bresson’s actors is thus found instead in the dextrous movements of their fingers, palms, and wrists, slyly penetrating the coats and purses of unsuspecting strangers. The sheer intimacy of the act and the fluidity with which Bresson’s camera traces its movements almost is virtually erotic, drawing pleasure from the slightest of human interactions. It is a stimulating transgression for Michel, who often makes eye contact with his victims as if engaging in contactless foreplay, before invading their personal space and claiming their valued possessions as his own. This loveless world which cannot draw so much as an empathetic close-up from Bresson’s camera has effectively left deviancy as the only remaining source of connection.

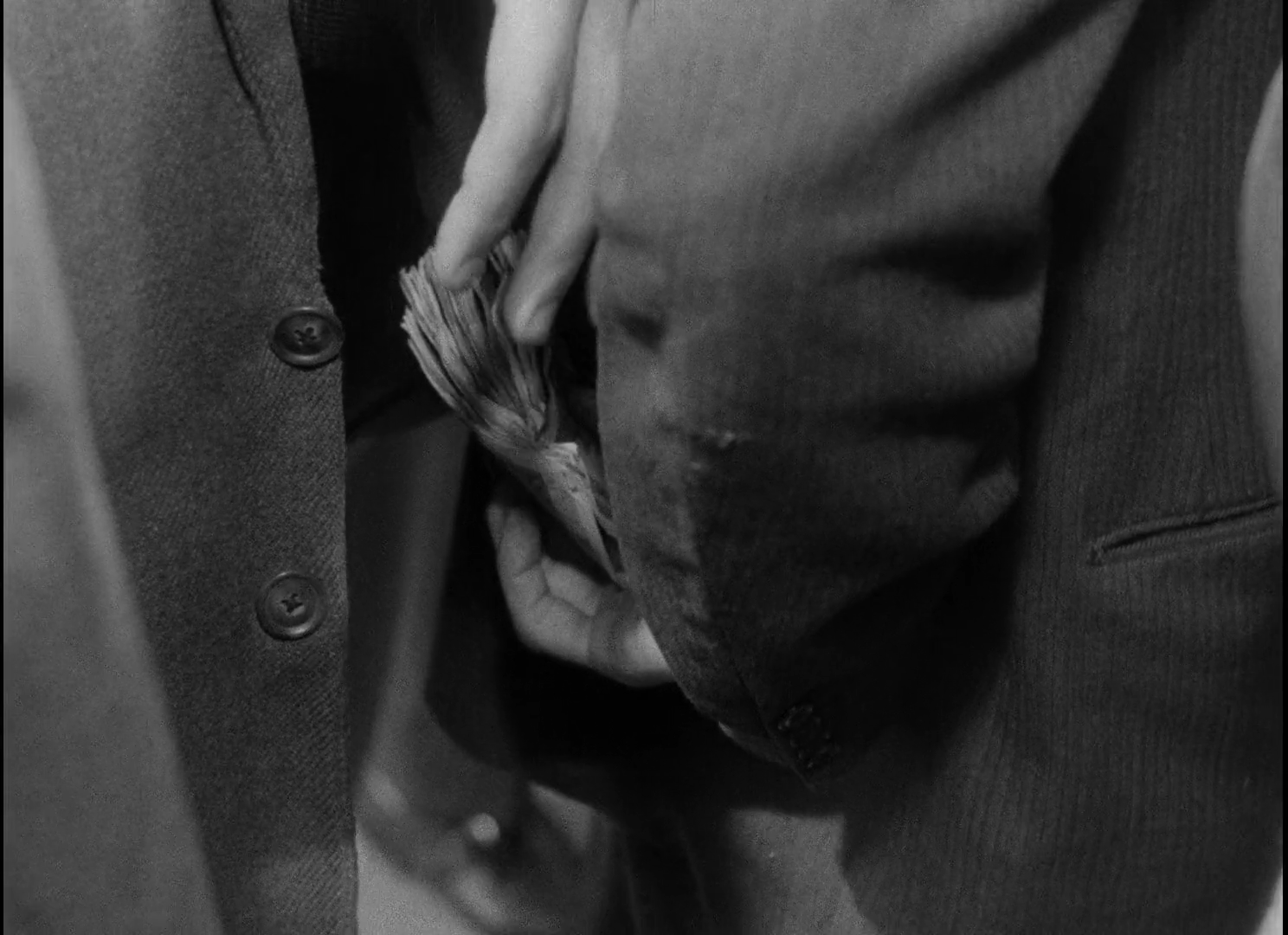

The time that Michel spends training with a more skilled pickpocket marks the height of his ecstatic freedom in the film. There is often a rhythmic flow to Bresson’s editing, cutting between the excited action of hands and that stillness of Michel’s detached gaze, and here it is smoothly distilled into a montage of methodical focus as we watch his tuition. The camerawork is as nimble as the actors themselves, studying the subtle movement of a watch slipping off a wrist or the latch on a purse clicking open. Bresson is even happy to let go of all dialogue and voiceover in these moments as well to advance his narrative visually, accompanied only by a subtly augmented sound design or excerpts of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s French Baroque symphonies.

What could ruin such an invigorating streak of successful robberies as this then? For Michel, a conscience comes in the form of two women, neither of whom necessarily imprint their own principles on him and yet still unknowingly impart a sense of disappointment. The first is his mother, who he has emotionally distanced himself from over the years and is now lies deathly ill in her apartment. She has been happily accepting his financial support for some time, but so too has he been stealing from her own funds – a cruel exploitation of power that he has been happy getting away with for as long as she remains ignorant. Only after her passing does he realise that he had not been so subtle, and that she had protected him from authorities when one of these thefts was reported by her neighbour, Jeanne.

The attraction that Michel shares with this other woman is marked by an ambiguous apprehension on both sides. The distance that he keeps with every other person outside of his victims divides them too, and yet this is also a recognition here that to pursue romance with her while pickpocketing would be to lead a double life – almost like an affair, if we are to equate his theft with intimacy. The guilt that he feels does not emerge from those arbitrary social norms he has shunned, but rather an internal, authentic care for the wellbeing of others, which now drives him to run away in shame. Like so much of this narrative, Michel’s time away flits by with little more than an ellipsis, communicated once again through a diary entry that brings him back where he started.

“From Milan, I went to Rome, before continuing on to England. I spent two years in London pulling off good jobs. But I lost my earnings at cards or wasted them on women. I ended up in Paris, drifting and penniless.”

Only by finding Jeanne again is Michel inspired to actually pursue honest work back home, and yet his impulse to carry out old transgressions remains a compelling desire he cannot shake. The site of his first pickpocketing at the start of the film is also his last – Longchamp Racecourse is a prime location for stealing from rich citizens, and once again Bresson submits us to tantalising close-ups of Michel’s hand delicately reaching for and withdrawing a giant wad of cash. This time though, we are struck with a quiet chill as a second hand reaches into the frame, slowly descending from above like a predator creeping up on its prey. There is no cut back to a wide shot after the handcuffs are slapped on his wrists. Just another dissolve to black, like so many other elliptical scene transitions in the film, excising whatever sensational thrills might have been implied in a direct depiction of his arrest.

In prison, Michel admits that it isn’t the physical restraints which disturb him so much as the mere idea that he dropped his guard. Running away from his guilt is no longer an option, now that it has trapped him in a permanent reminder of his own moral failings. Bars divide him from Jeanne when she comes to visit, prohibiting that closeness which he could only ever attain through pickpocketing. As both sidle up to each other now though, Bresson accomplishes a sincere affection we have not yet seen in the film. An imperceptibly slow dolly shot draws us into a close-up of their faces nestled against each other, touching through the gaps in the bars between them, and formally breaking from the constant mid-shots of cool dispassion. “Oh Jeanne, to reach you at last, what a strange path I had to take,” Michel reflects in voiceover. For a man who so eagerly draws pleasure from violating the physical space of others, the journey to finding genuine love free from intimacy is a very strange path indeed.

Pickpocket is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel and SBS On Demand.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1950s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best 250 Films of All Time – Scene by Green