Louis Malle | 1hr 50min

To engage with the conversation that rhythmically flows throughout My Dinner with Andre is to sit down and partake in that meal with old colleagues. Wally is short, squat, and reasonably content with his mundane life in New York City, despite struggling as a playwright. “I mean, why is it necessary to have more than this, or to even think about having more than this?” he ponders, challenging his far more fanciful friend Andre who has returned from overseas adventures with grand philosophical ideas. Even while seated, he looms much taller than Wally, with an angular face and deep voice that resonates a complete self-assurance.

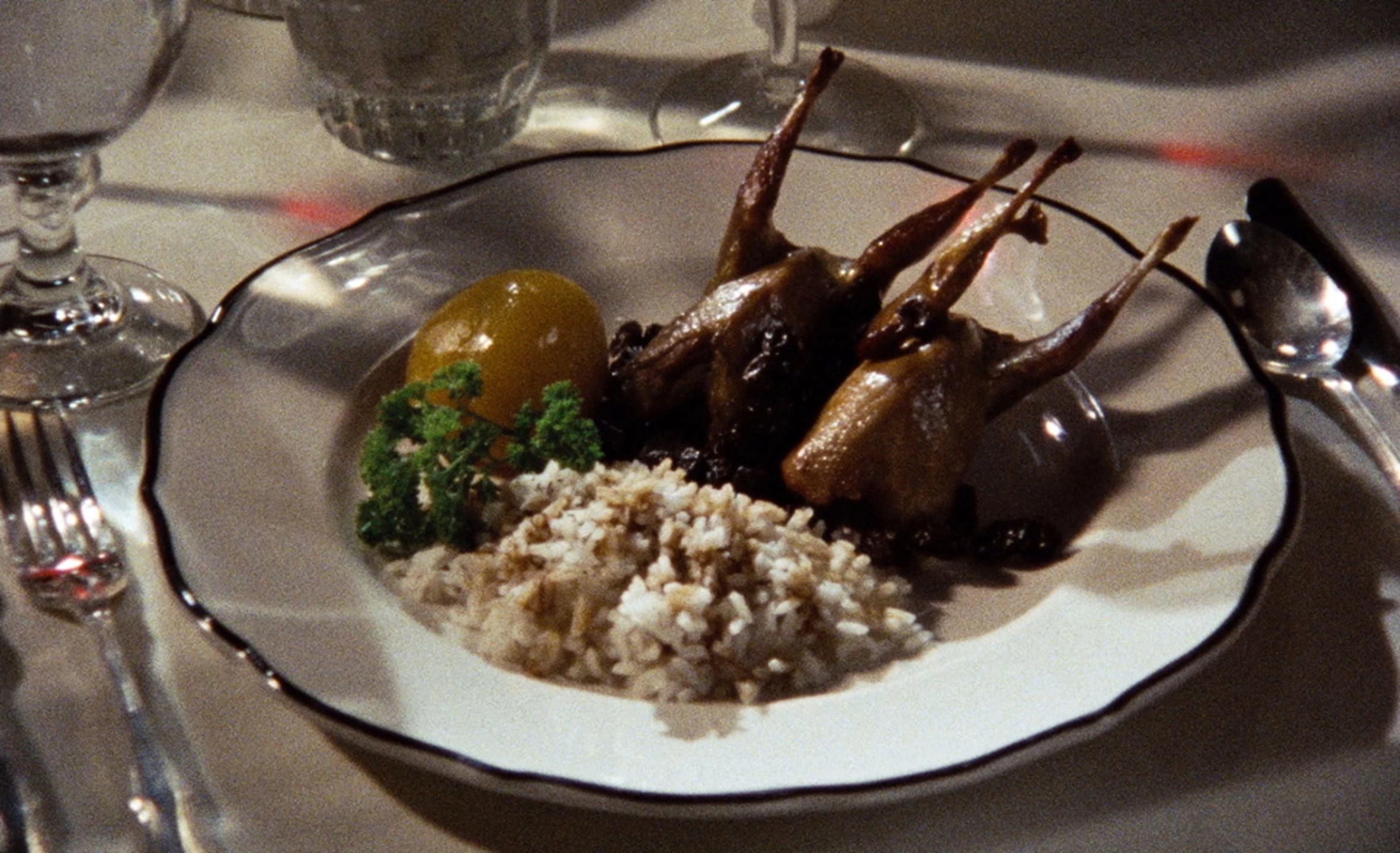

These are the only characters who serve our total immersion into the film. The few others present are the fellow restaurant patrons and staff who pass fleetingly through shots, never speaking anymore than a few words a time, yet serving an important purpose in the film’s subtle structure. Besides a pair of bookended montages that follow Wally’s internal voiceover through New York’s streets, My Dinner with Andre is set entirely in real time over a nearly two-hour conversation, only ever interrupted by the appearance of a waiter taking orders and serving meals. In effect, these courses are our chapters, punctuating the point at which one topic segues into the next. By the end, we too have had our fill of intellectually stimulating conversation, which has proven to be just as hearty as their feast of quail, fish, and wine.

Perhaps even more fascinating than the meeting itself is the way it reflects a pair of a diametrically opposed men invariably finding value in their disagreements. Though actor-writers Wallace Shawn and André Gregory are clear that the connections between them and their characters are thin, the conflict is at least partially based on their own natural tendencies. Gregory himself has acknowledged in real life that his own zealous search for religious meaning could carelessly slip into totalitarianism, and that he imbued this into “a character who is driven, obsessed and narcissistic, who delights in the sound of his own voice.” Indeed, Andre’s monologues about working with an experimental theatre troupe in Poland, the fascistic undertones of The Little Prince, and self-comparisons to Nazi architect Albert Speer seem to be dictated by little more than the whims of an intelligent ego.

This entrée is but a taster of the point he will eventually arrive at though during the main course. Andre is thoroughly upset with the “insane dream world” that modern society is so caught up in, forcing people to perform roles which are “hiding the reality of ourselves from everybody else.” Of course, the great irony here is that Shawn and Gregory too are playing alternate versions of themselves, seeking truth from the fiction they have created. Wally remains silent for a time, squinting in sceptical bemusement at his friend’s existential soliloquys, before he comes forward in opposition. Unlike Andre, he stumbles and flails towards his point, but there is a sincerity to his run-on sentences that messily consider the joy of life’s small pleasures.

“Well, Andre, I mean, my actual response – I mean, Andre, really – I’m just trying to survive – you know? I mean, I’m trying to earn a living, I’m trying to pay my rent and my bills. I mean, I live my life, I enjoy staying home with Debby, I’m reading Charlton Heston’s autobiography, and that’s that. I mean, occasionally, maybe, Debby and I will step outside and we’ll go to a party or something, and if I can occasionally get my little talent together and write a play, well then that’s wonderful, and I enjoy reading about other little plays that people have written, and reading the reviews of those plays and what people said about them, and what people said about what people said.”

One might almost think that dialogue like this was improvised were it not for the fact that the two writers have been so open about their creative process. Just as Gregory has expressed distaste towards his character’s egotistic tendencies, so too has Shawn expressed his desire to rid himself of the insecurities he poured into Wally, “because that guy is totally motivated by fear.” The catharsis for both men is evident, infusing My Dinner with Andre with naturalism on almost every level of its construction, and yet there is also a Brechtian clarity in the calm distance placed between the viewer and the abstract ideas being reflected on. This intent even manifests directly in Andre’s own reflections.

“When you think of Bertolt Brecht – he did something that was perhaps the most amazing thing of all. You know, he somehow created a theatre in which people could observe, that was vastly entertaining and exciting, but in which the excitement didn’t overwhelm you. I mean, he managed to allow you the distance between the play and yourself that in fact two human beings need in order to live together.”

Therein lies the understated brilliance of this screenplay that is so in tune with the quirks and rhythms of authentic speech, yet also refined to a sharp point in its formal presentation. As director, Louis Malle’s artistic voice is not quite felt on the same level as Shawn and Gregory’s, unfortunately refusing to engaging with any sort of distinct visual style. Still, he does insert quiet flourishes every now and again, such as the extremely slow zooms set that draw us closer into Andre’s face as he tells another fantastical story, or the mirror which catches his reflection behind Wally’s head so that both their faces are displayed at once.

There is also an amusing warmth to the way in which Malle lingers on unspoken interactions, at one point holding on Wally and the waiter’s awkward eye contact after Andre lets out an excited cackle. Much like Richard Linklater’s organic experiments in narrative structures, it is in the accumulation of small moments like these that lets time languidly slip away without the artifice of invasive editorial manipulations.

So intoxicating is this conversation between Wally and Andre that not even they realise that all the other customers have left the restaurant. Perhaps it wasn’t for the imposing constraints of society’s closing hours, they might have kept on going forever. An exit to the outside world signals a shift in Malle’s style, now heavy on montages, handheld cameras, and location shooting on New York’s streets, much like the opening. Instead of taking a graffitied subway though, Wally rides the taxi home – a slight but unusual departure from familiar habits, motivated by his friend’s generous covering of the bill. For all of Andre’s eccentricities and conspiracy theories, his anti-conformist philosophies have clearly taken root. Where Wally’s introspective narration at the start of the film was fraught with stress and anxiety, there is now a deeper, joyful connection between him and his environment.

“There wasn’t a street, there wasn’t a building, that wasn’t connected to some memory in my mind. There, I was buying a suit with my father. There, I was having an ice cream soda after school. And when I finally came in, Debbie was home from work, and I told her everything about my dinner with Andre.”

There need not be conflict between these two halves of the human experience represented by old friends, but there is rather a soulful revitalisation found in the act of sharing food and culture. What My Dinner with Andre lacks in cinematic panache, it compensates for with a three-course meal of acute, provocative screenwriting, uncovering the raw essence of its contrasting characters within the most common of modern-day settings.

My Dinner with Andre is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1980s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green