Todd Field | 2hr 38min

Todd Field’s return to filmmaking comes as a painstakingly formal study of that complicated passion which has been such a burden on him during his sixteen-year hiatus. Struggling to have any of his previous visions financed since 2006’s Little Children, the culture of high art which orchestral composer and conductor Lydia Tár comfortably inhabits has long lingered just out of his reach. Even now as he finally arrives there with his major comeback though, he offers its industry neither condemnation nor loving adoration. Lydia has undoubtedly exploited its systematic corruption for many years, but this does not detract from the evidence of her own immense talent. Tár remains at a chilly distance from the casually cruel subject of its interrogation, and it is at this arm’s length from the audience where Cate Blanchett unleashes the full, daunting force of an undeniably gifted abuser, digging her nails into Lydia’s crumbling musical empire.

In the lengthy interview which opens Tár, her impressive, carefully curated credentials are read out beneath a montage of her suiting up, and when questioned about her role as a conductor, she implicitly likens it to that of a god. Objective qualities like time obey the movement of her hand, and no sound can be made without her direction. This ego is something which echoes through to her personal life as well. In one scene, the incessant pen clicking of her assistant conductor Sebastian only ends when she forcefully snatches it away. Likewise, in the lecture theatre at Julliard School where she trains young musicians, the nervous bouncing of one student’s leg grinds away at her patience until she physically puts her hand on it.

Field efficiently lays the groundwork of Lydia’s ideals in this scene, offering her an adversary in the form of a queer, BIPOC pupil who asserts his distaste for Bach’s music, and justifies it via the composer’s identity as a white cis male. Blanchett’s deep voice resonates with confidence through her questioning of his beliefs, which then moves to a gentle demonstration of his erroneousness – “The narcissism of small differences can lead to the most boring conformity.” Finally, she brings her soliloquy to a close with a brutal evisceration of his identity politics, using Icelandic composer Anna S. Þorvaldsdóttir as the subject of her example.

“Now, can we agree on two pieces of observation. One, that Anna was born in Iceland, and two, that she is, in an older teacher kind of way, a super-hot young woman. Show of hands. Alright, now let’s turn our gaze back to the piano bench up there and see if we can square how any of those things possibly relate to the person we see seated before us.”

The ten-minute long take which guides this scene serves multiple purposes in its examination of Lydia’s power play. Field’s deep focus lens keeps landing on elegant compositions all through its extensive duration, constantly underscoring the shifting dynamic. As teacher and student start on equal footing, the tiered auditorium rises behind them like a pyramid, assuredly centring them both in a dominant stance. Later, Lydia seats him in the audience and lets the orchestra fan out behind her, subtly taking the position where he stood just a few minutes ago. Gradually he becomes smaller in the frame until he storms out in fury, and she strikes him with one final, poisonous barb.

“The architect of your soul seems to be social media.”

The expert execution of this single shot and Lydia’s delivery of a proto-defence against the accusations she will suffer later are just the start of this scene’s formal acuity. The narrative economy demonstrated in its eventual return as an online video is simply remarkable, as its truth-twisting, spliced-up clips contrast with our initial real-time observations, where no editorial manipulation was present.

Beyond this single confrontation, Field frequently returns to phone screens that we see covertly filming Lydia and texting unknown recipients, turning the constant surveillance of the modern world into a weapon of invasion and revenge. In this way, he leans heavily on his Michael Haneke influence, and specifically the driving tension of Cache where a series of anonymous recordings destabilise the lives of a wealthy couple.

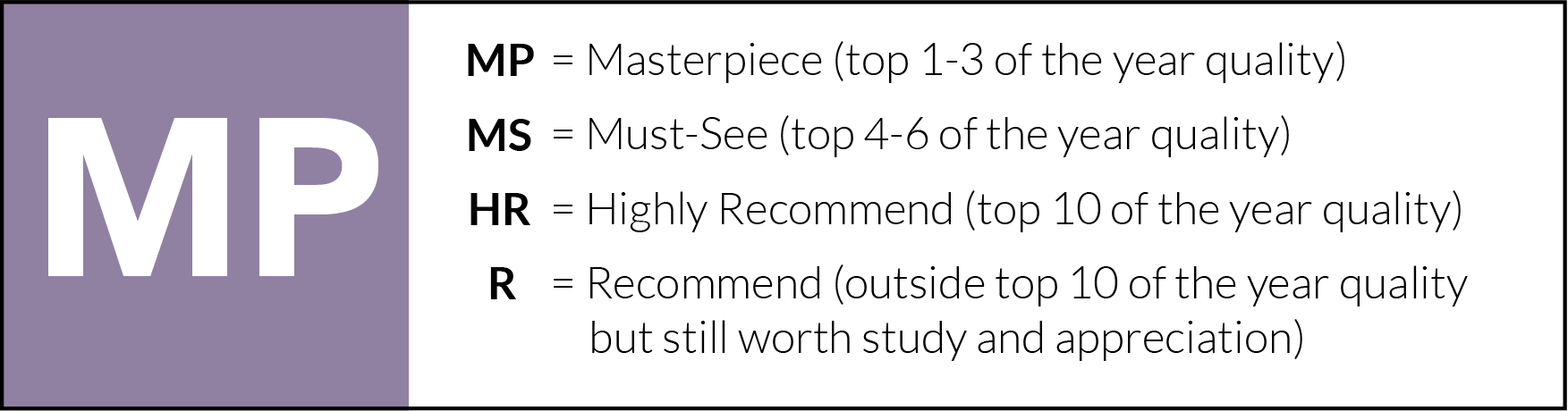

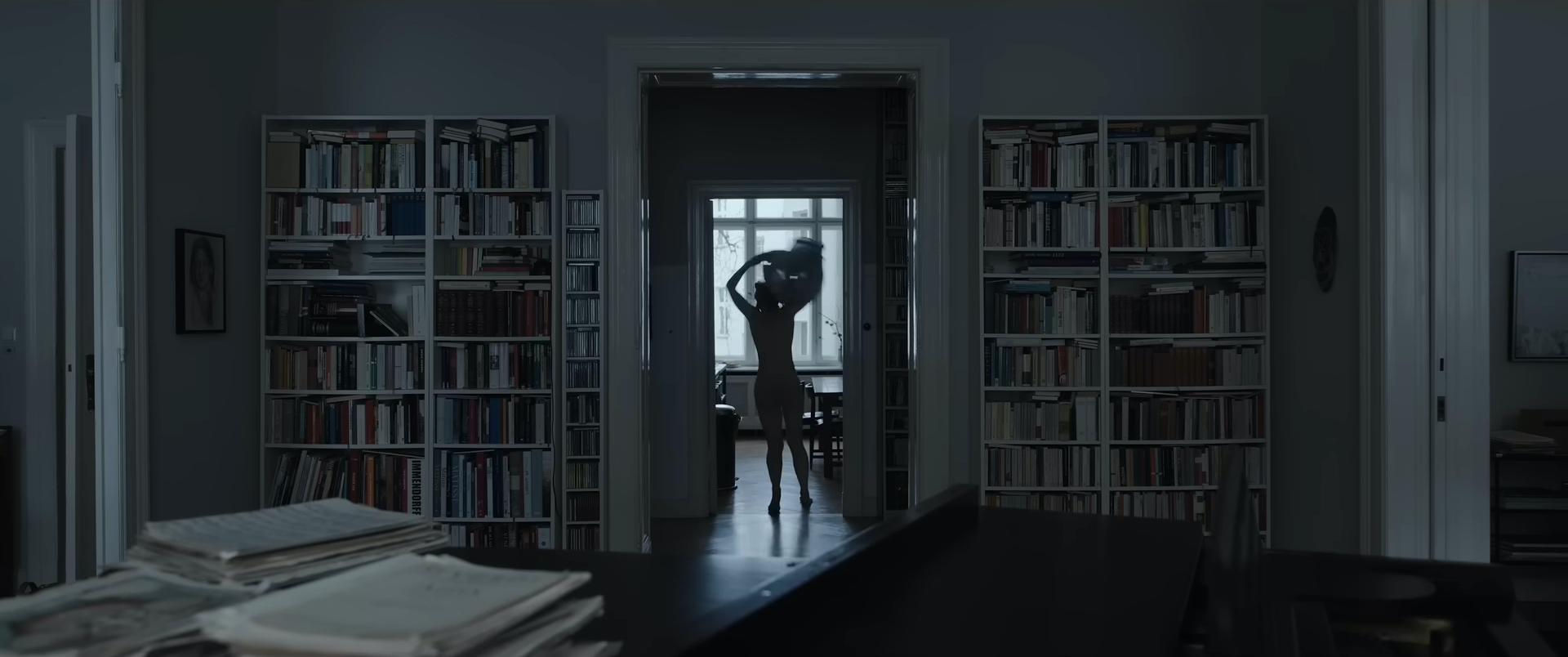

To examine these similarities further, Tár’s psychological study of a disturbed musician makes for a fascinating companion piece to The Piano Teacher, and the bookcases which so often fill out Haneke’s mise-en-scène here line the walls of Lydia’s modern German apartment. Inside its vast concrete walls, narrow corridors, and sleek interiors, Field crafts the image of an austere woman who has fashioned her world to Brutalist perfection.

Even in her concert hall, several storeys of angular, wood-panelled balconies surround the stage in some brilliantly off-kilter shots, matching the character to her impressively designed workplace. Quite curiously, it isn’t until an hour into the film that we even see her take the spotlight here and conduct for the first time. When the scene does finally arrive though, her arms violently bring in the sound of crashing thunder. From an extremely low angle, Blanchett aggressively throws her entire body into each beat and cue, like a dance that furiously produces its own musical accompaniment, and from there Field’s incredible camera placement only continues to trace the power of her movement.

On the other end of Lydia’s emotional journey, he brings equal Kubrickian precision to her gradual disintegration. Several key narrative beats unfold with the camera hanging on the back of her head, resisting the urge to cut to a close-up which might tempt us towards some kind of empathy. The trap she has found herself in is one of her own making, yet she still seeks multiple escapes from its confines. The repetition of scenes where she is simply running, boxing, and wandering around the house imply efforts at securing a stable mundanity, disconnected from the intensity of her work life.

And yet despite these attempts, this anxiety still slips its way into her mind. In one sequence frighteningly rendered as pure psychological horror, she winds up in a dark, abandoned building with a mysterious creature that pitter-patters across the wet ground and ferociously growls at her. When she finally emerges, she trips on the stairs and injures her face. How shocking it is to see this perfectly composed woman put a foot wrong, and when she faces up to her orchestra the next day, she deliberately avoids divulging the truth of her embarrassing misstep. With the time she spends editing her own Wikipedia page, and the coverup of her real birth name, Linda Tarr (note the plain ‘a’ instead of the accented ‘á’), bit by bit we start to see the importance she places on her own public image – far more than she previously let on in her diatribe against identity politics. In fact, it wouldn’t be a stretch to believe that she was never really personally mentored by Leonard Bernstein at all.

Even more superbly formal patterns of her mental demise emerge at night-time. When Lydia is able to sleep, dreams of whispers and surreal images swirl around in her restless psyche. When she lies awake, it is usually because of a sound reverberating through the house, sensitively connected to her troubled conscience – a ticking metronome after failing to uncover the source of a woman’s guttural screams, or the hum of a fridge upon passing over her assistant for a promotion. Like the clicking of Sebastian’s pen, these relentless noises chip away at her sanity, reminding her that life is not an orchestra where every sound bows down to her whim.

Is it guilt that Lydia is feeling in moments like these? Perhaps a paranoia of what may be coming to get her? Field is withholding when it comes to the details of her misdeeds, leaving a purposeful ambiguity around our own attitude towards this character. No doubt she can be utterly seductive at times, playing to Blanchett’s poised, assertive presence as an actor in complete control of her craft. For a time, we may even make excuses for her brusqueness, as the way she threatens her daughter’s school bully and calls herself Petra’s “father” has a slight edge of dark humour to it. For those who know her though, the respect she commands is tinged with fear. It is only when she lets go of old colleagues and acquaintances that they finally find the courage to question her authority, and therein lies the primary catalyst of her downfall.

The name Krista is tossed around with reservation a few times before we start to pick up on her significance in Lydia’s life. Our only glimpses of her are as an out-of-focus, red-head figure watching her old mentor from a distance, like a ghost ominously haunting her for mysterious, past transgressions. Their previous relationship is clarified a little when we start to see Lydia take a liking to young, Russian cellist Olga and begin to twist a few arms in her favour. Field is never explicit about what exactly goes on between her and her protégés, and so for a while it is tempting to question whether the allegations levelled against her are fully accurate, and yet at least one thing becomes absolutely apparent – Lydia Tár is not a good person.

What is there to make of her final scene that sends her plummeting from high to lowbrow culture? Field is cryptic with the look that one young prostitute gives her from within a line-up, astutely arranged in the formation of an orchestra. Like Olga, the one who makes eye contact is labelled number 5. There is something about this that churns Lydia’s guilty stomach. How much remorse does she have for her actions, and how much of that is purely selfish? Firm answers don’t come easily in Tár, leaving us to wonder whether a new cycle of abuse is about to begin as she stands in front of a new orchestral ensemble, significantly less revered than the Berlin Philharmonic. In that moment though, it barely matters. She pours every drop of musical passion she has remaining into it, once again deified by the act of boundless control. Lydia Tár’s new reign may be more menial than ever, but even now her ravenous ambition still approaches the smallest of jobs with an unflinching, formidable authority, patiently waiting for the day she moves back on up the ladder.

Tár is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: 2023 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2022 – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of the 2020s Decade (so far) – Scene by Green

My review of Tár

First off, this feels like an educational movie at times. That Juilliard scene can work as a standalone lecture or a lesson as much as it maybe establishes the character of Lydia. I also find interviews and conducting scenes less cinematic and more inclined towards almost being an educational movie made for music students. Highly methodical and lecture-based. (I don’t mean it as a compliment- it’s the antithesis of cinema itself- throws “show don’t tell” theory off the window and almost tells everything in a pragmatic fashion- the character is mainly established through the lecture in Julliard now compre it with how PTA establishes Barry in Punch Drunk Love).

I find the camera movement in almost all the scenes simple and pretty much not fantastic. It’s nearly static (not as compliment like for films such as Jackie and Spencer – where the mise-en-scene and static camera is the art in itsef) aligned more with interview videos.

Conducting, interviews, lectures constitute a portion of the film and nothing kinetic in terms of filmmaking style. Again ambitious iedea but pretty non-ambitious execution. Those scenes drag. Like in Juilliard scene – it drags a Little bit still watchable only because of Cate Blanchett’s performance and and highly educated writing (and when is that a good sign for a movie).

It’s not beautiful to look at. Compare it to some of the movies from this very same year or Oppenheimer and Poor Things. I dare anyone look into my eyes and mention Tár’s visuals in same breath as these films. Even similarly dense ones like I’m Thinking of Ending Things from this very same decade. Are visuals as simple and direct even an achievement in 2022. I don’t think so. Amadeus was made in 1984 and has many conducting scenes but Is visually stunning and so brilliantly directed. Pure bliss.

I don’t think it’s a major achievement for anyone involved. Todd Field is NOT an auteur. His three films are vastly different. I find In the Bedroom to be his strongest work to date. It’s much tighter than this. Never drags. Better screenplay and a fantastic performance by Sissy Spacek. Little Children is not a major accomplishment.

Cate Blanchett is really good here but it’s NOT one of the all time best. A lot of actors have a lot of equally strong performances in a lot of movies of this level. Isn’t even her strongest.

I overall find this film lacking in execution. When I watched it before I thought it’s ambitious enough to be R/HR. But this time when I watched it , it dragged even more. It’s not The Master which gets better everytime you watch it because you find more visual cues. It belongs more in the lineage to Kramer vs Kramer, where the more number of times you watch it the more you realise how much the movie is actually rooted in script and performances. I’ll say it’s a R for now

I disagree with equating great visual language = beautiful frames. If that were the case, so many legendary movies would not be called great movies. Tar’s visual achievement lies in how precise and meaningful each frame is – the mis en scene does a splendid job of unveiling visual motifs, symbols and character detail – insights into Tar’s past, her superstitions and weird beliefs, and supernatural allusions to her downfall – it is almost like the forces of nature coming together to tell her that “Time’s up”.

I feel that Scorsese sums it up well – “What you’ve done, Todd — it’s a real high wire act, all of this is conveyed through a Masterful Mise-en-scène, as controlled, precise, dangerous, precipitous angles and edges geometrically kind of chiseled into a wonderful 2:3:5 aspect ratio of frame compositions. The limits of the frame itself, and the provocation of measured long takes all reflecting the brutal architecture of her soul — Tár’s soul.” And I also came across a really great article talking about the approach to its cinematography – https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/tar-cinematography-florian-hoffmeister-1234807120/.

Honestly, I was one of those who felt that it was quite overrated, but I have watched it twice since and had a renewed appreciation for all that Field is doing – whether it is calibrating the editing of the movie to rhythmic beats that resemble that of a symphony, using angles and lines in production design to allude to power dynamics, the brutalist frames, the almost otherworldly final few minutes that feel straight out of a dream, and some killer shots like the transition of her playing the piano to the super low angle shot of her conducting, the sequence in the fishbowl, the one point shot of her rushing to the stage, the dream sequence where she catches on fire with a tree branch almost verging on piercing her – I could go on and on.

I agree that Field is not an auteur but I feel that’s beyond the point. He has achieved something wholly unique – by exercising a lot of control, creating a fascinating world and not falling to the trappings of a conventional dazzling ‘orchestra/conducting’ movie. I think that directors like Cuaron, PTA, Scorsese praising it acknowledges his achievement. But again, each to his own!

Very well said, and a great article as well.

I disagree with your masterpiece rating of this film. Calling it a masterpiece means a film ahead of say The Deep Blue Sea -a film a recently saw and consider it as a high end MS because it isn’t on the level of Terence Davies’ Distant Voices Still Lives and The Long Day Closes, and calling Tár a masterpiece means putting it the same line as these films or for a recent comparison in same line with Oppenheimer. And comparing Tár with these films is a disrespect of them.

These films have a lot going on for them. Tár is an uncinematic execution of a very ambitious idea. Whereas these films may not be very high on the themes that they’re taking on but they are cinematic bliss. Muscular.

I don’t say you’re wrong but I think it’s either of the two – at multiple watches you’ll find it more and more reliant on JUST the dialogues and Blanchett’s performance or I’ll find it more and more visually stunning. Let’s see.

I would be willing to listen to arguments that it should be lower, but I disagree that it somehow disrespects other great films. Their quality is independent of Tar’s.

I’m not sure I can add anything right now that I haven’t already mentioned on this page, but these are some great videos that dig into its style:

https://youtu.be/kUf3fu3mSDI?si=ggdQ-NpfYSVas1NU

https://youtu.be/9EDmW6Xmmfw?si=h6s0iwAhX3cQcRCY

Pingback: 2022 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green