“In themselves, the pictures, the phases, the elements of the whole are innocent and indecipherable. The blow is struck only when the elements are juxtaposed into a sequential image.”

Sergei Eisenstein

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. Battleship Potemkin | 1925 |

| 2. Strike | 1925 |

| 3. Ivan the Terrible | 1944-46 |

| 4. Alexander Nevsky | 1938 |

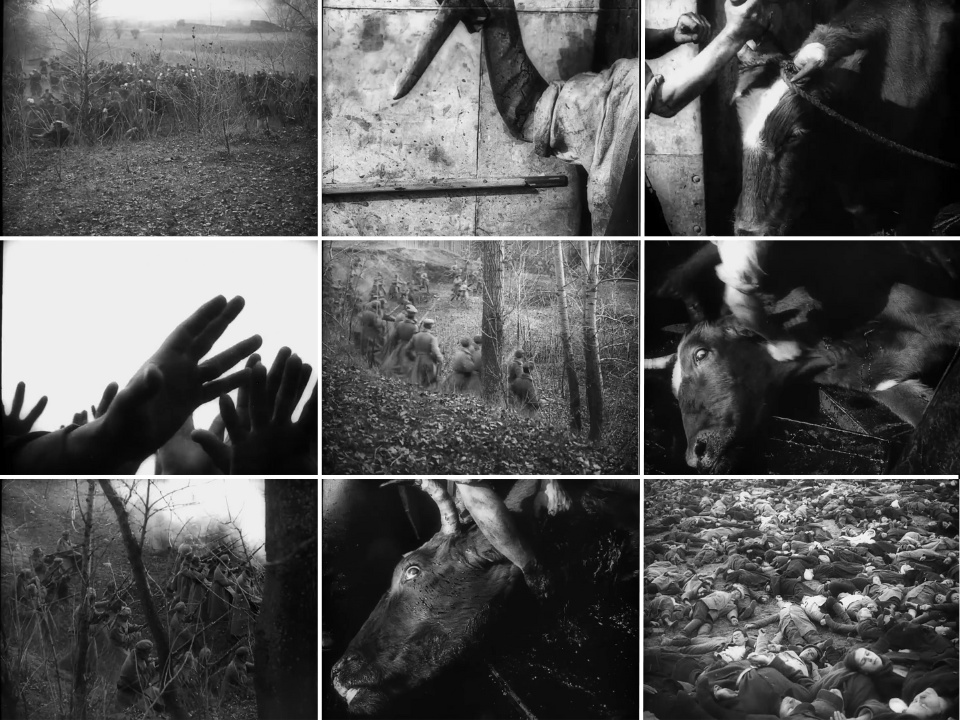

| 5. October: Ten Days That Shook the World | 1928 |

Best Film – Battleship Potemkin

Eisenstein’s second feature stands tall among the great works of cinema, and if that isn’t enough, it is also the best-edited film of all time. It is very much a product of the Soviet Union in its earliest years, though under the purview of an artist who understands his craft on an intimate level, it also transcends mere propaganda. The five methods of montage that Eisenstein developed in the early 1920s are cleanly distilled here in their purest forms, and from this mechanical arrangement of moving images, he composes a narrative that identifies the collective masses as their own champions. No discussion of Battleship Potemkin can go without mention of the Odessa Steps sequence either, where he orchestrates a cinematic assault on the senses into a sweeping indictment of the Tsarist regime.

Most Overrated – October: Ten Days That Shook the World

The TSPDT list’s ranking at #452 might only be off by 100 spots or so, but this isn’t a great travesty. Although it lacks the formal rigour of Strike or Battleship Potemkin, this is a superb demonstration of Eisenstein’s intellectual montage in action, telling the story of the October Revolution through large scale set pieces and profound political symbolism.

Most Underrated – Strike

A ranking of #654 on TSPDT is too low for what is one of history’s most impressive directorial debuts. Rigorous formal purpose underlies every visual and editing choice that Eisenstein makes here, using a factory strike to represent a much larger class struggle at play throughout early twentieth century Russia. While cinema was still young, few people understood its immense power in shaping political thought, and even fewer mastered this skill through a virtuosic command of moving images as Eisenstein does in Strike.

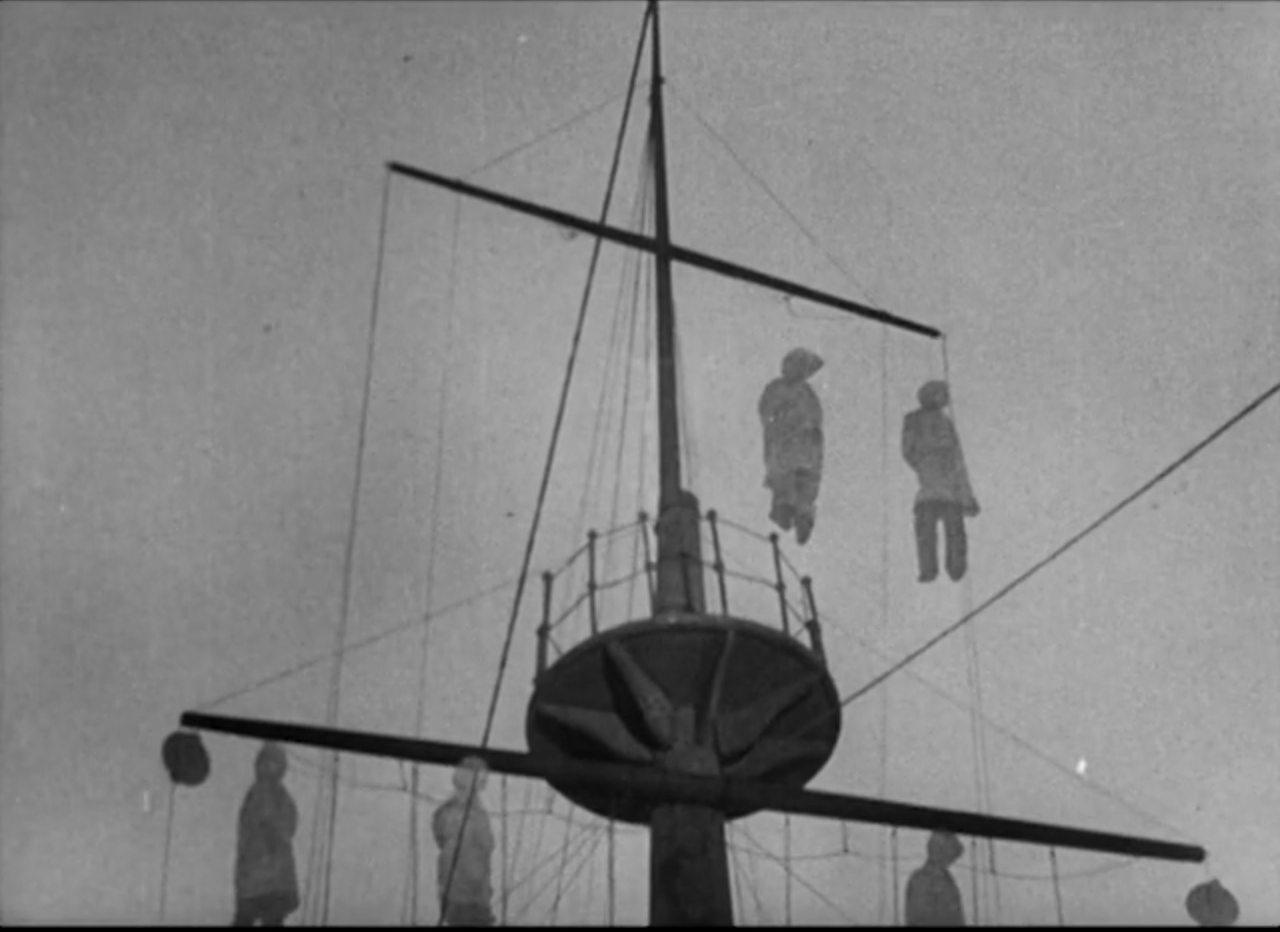

Gem to Spotlight – Alexander Nevsky

Tempered by the Soviet state, Eisenstein approached his fourth feature as a fresh start. This film may not possess the formal innovation of his silent works, yet its venture into sound cinema maps out its historic clash of medieval armies with great finesse, and builds to a grand thirty-minute climax at the Battle on the Ice. The fantastic score from Sergei Prokofiev certainly doesn’t hurt either, rumbling and sweeping across battlefields to accompany the titular Prince’s victory over the merciless Teutonic Knights.

Key Collaborator – Eduard Tisse

The other option here is Grigori Aleksandrov who assisted in various capacities, whether as an actor, assistant director, or co-director. Nevertheless, it is Tisse who had the most tangible impact on Eisenstein’s as his perennial cinematographer, shooting all his films from Strike to Ivan the Terrible. It can be easy to underrate these visuals next to the sheer triumph of editing on display, but the precision that that Eisenstein applied to montages is well supported by Tisse’s tremendously striking imagery, dipping into expressionism through lighting, blocking, and camera angles.

Key Influence – D.W. Griffith

There are few influences to draw on this early in film history, but the comparison between these directors is especially apt given their innovations in the realm of editing and establishing the foundations of film language. Despite their vastly differing political ideologies, Eisenstein admired Griffith’s ability to evoke strong emotional reactions from his audiences, often through staggeringly large set pieces with magnificently intimate close-ups interspersed throughout.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

Methods of Montage (1925-29)

Having studied architecture and engineering in Petrograd, fought in the Russian Civil War, and explored the world of experimental theatre, Sergei Eisenstein’s entry into cinema resulted from an amalgam of influences. It was specifically in those days of directing plays that he developed what he would call the ‘Montage of Attractions’ – the theory that by juxtaposing conflicting artistic elements, an audience could be led to specific emotional or ideological conclusions, creating a new idea that isn’t contained in any individual component. This was born from the philosophy of dialectics developed by Hegel in the early 19th century, which proposed that the evolution of human thought relied on a three-part process:

- Thesis: A particular idea is posed.

- Antithesis: This idea is contradicted.

- Synthesis: The resolution of this conflict, leading to a new idea that incorporates elements of both thesis and antithesis.

Karl Marx would later develop this through a more material lens, framing the thesis as capitalism, the antithesis as class struggle, and the synthesis as a new socioeconomic order – socialism. Inspired by Marx’s writing, Eisenstein sought to similarly integrate dialectics into his own theory of montage.

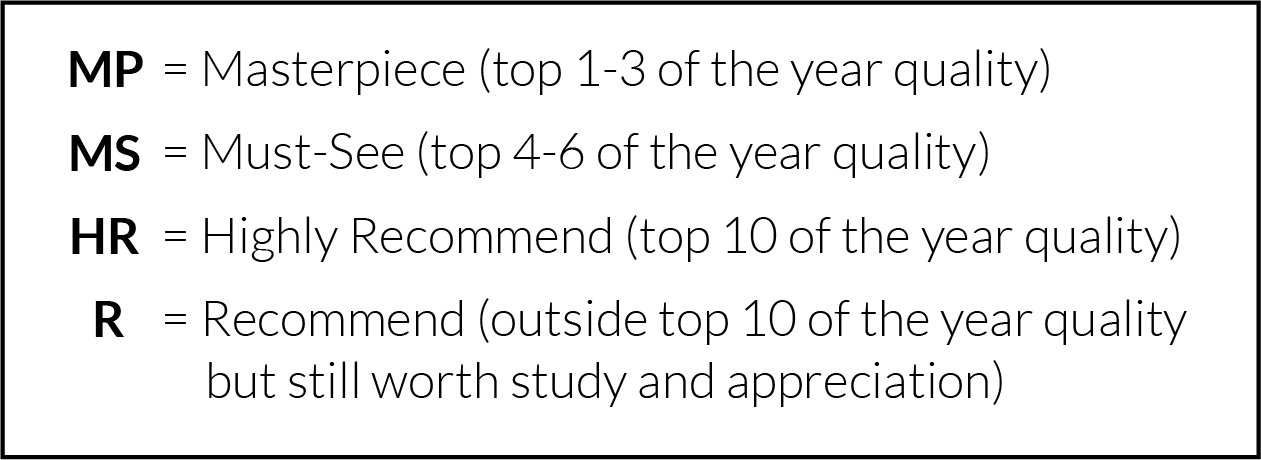

- Thesis: An initial image (eg. the Tsarist police massacring factory workers and their families).

- Antithesis: A second image in conflict with the first (eg. a bull being slaughtered at an abattoir).

- Synthesis: The reaction of the audience, who resolves the two conflicting images into a new idea (eg. the brutal dehumanisation of innocents).

Just as Eisenstein was writing essays on these avant-garde ideas, the Soviet government was growing interested in cinema, recognising its potential as a method of mass propaganda. As such, he was one of several artists commissioned by the state to make films, officially commencing the movement of Soviet Montage Theory along with Lev Kuleshov (famed for devising the Kuleshov effect), Vsevolod Pudovkin (Mother), Alexander Dovzhenko (Earth) and Dziga Vertov (Man with a Movie Camera). There are subtle differences in the way each approached the art of montage, though it was Eisenstein who found the greatest artistic success in his five methods of montage:

- Metric montage: Cutting based on a specific number of frames per shot (eg. a quickening tempo underscores the rising tension of sailors preparing to revolt in Battleship Potemkin)

- Rhythmic montage: The adjustment of each shot length according to the movement unfolding onscreen (eg. watching sailors run across the frame during Battleship Potemkin’s mutiny)

- Tonal montage: Editing together shots that evoke a specific mood or feeling (eg. crowds mournfully gather around the body of a fallen hero in Battleship Potemkin)

- Overtonal montage: The combination of metric, rhythmic, and tonal montages to induce a more complex emotional response (eg. the devastating Odessa Steps scene in Battleship Potemkin)

- Intellectual montage: The symbolic association of juxtaposed shots (eg. intercutting religious idols with the advance of the Imperial Army in October, linking the tyranny of religion to nationalism).

Eisenstein’s theories were inherently opposed to the idea of seamless continuity editing and straightforward plotting, but rather suggested montage could be a dialectical form of thinking in images. Shots are meant to collide, he believed, requiring spectators to generate the resulting synthesis in their mind – a participatory act of creativity which is revolutionary in and of itself. It is certainly no coincidence that many of history’s most politically charged films feature this kind of fast-paced editing, such as D.W. Griffith’s contemptible valorising of the Ku Klux Klan in The Birth of a Nation or Oliver Stone’s conspiracy theories in JFK. On its purest level though, his montage theory can also be contained to a standalone shot with internal visual conflicts, such as heavy contrasts of light and dark or cutting through orderly frames with harsh, diagonal vectors.

It is thanks to this firm theoretical grounding that Eisenstein approached his first two films with enormous confidence. Strike and Battleship Potemkin were released in 1925, making for one of the strongest cinematic debuts and immediate follow-ups in history. Both are set in the days of pre-Revolution Russia when proletariats suffered under the tyranny of the Tsars and their feudalist state, and in true socialist fashion, he identifies the collective masses as their own champions rather than glorifying any single protagonist. Where Strike ends with the catastrophic massacre of innocents though, Battleship Potemkin leaves us with a hopeful look towards the future, revealing the sheer versatility of his editorial orchestrations to span humanity’s full emotional spectrum.

Here, Eisenstein also established a common motif that would continue to appear in his later films too – revealing the wickedness of his villains by depicting them as child killers. There is little room for moral ambiguity in these political fables, but it is upon this sheer disparity between good and evil that he builds his most invigorating montages, including perhaps the best-edited scene of all time in Battleship Potemkin’s Odessa Steps sequence.

The rapturous reception these early films received set Eisenstein on course to director October: Ten Days That Shook the World three years later. For the government, this was to be a grand dramatisation of the October Revolution in 1917, which saw the Bolsheviks topple the Provisional Government and officially establish the Soviet Union. Eisenstein no doubt delivers on spectacle here, and even continues his trend of opening with a quote from Vladimir Lenin, but he was evidently more interested in creating intellectual montages above all else. Although October was enthusiastically received by foreign critics, this decision to emphasise abstract visual symbolism was deeply unpopular with the Soviet government, pushing him to leave home and explore filmmaking prospects in the Western world.

Nevertheless, these early years were Eisenstein’s most fertile artistic period, and certainly his most unrestricted. The mathematical mind that he honed as an engineering student was the same which drove him to revolutionise cinema with logical precision, seeking to understand the compositional details of art from which profound sensory experiences are born. Dissolves were not merely used to indicate the passage of time, but could be woven into montages like a legato musical phrase, while close-ups of incensed faces might alternately be played with rapid staccato. To him, this was a radical mode of creative expression for the twentieth century, uniquely attuned to his own revolutionary ideals which would symphonically swell upon waves of moving images.

Historical Epics (1938-46)

The ten years following the negative reception of October were turbulent for Sergei Eisenstein. After briefly dabbling in documentaries and shorts, he set off on a journey through Western Europe with his frequent collaborators Eduard Tisse and Grigori Aleksandrov, where he continued to broaden his filmmaking network. Not long after though, his attempts to break into Hollywood each ended in failure, sending him back home to the Soviet Union where he met further disappointments. His only shot at making a comeback was by appealing to Joseph Stalin, who was now exerting a more extreme censorship of the film industry than ever before.

A new era in Eisenstein’s career was beginning, shifting his focus away from experimental celebrations of modern-day Russia and towards grand historical epics. For the first time, he was also centring individual protagonists, each of whom where real-life figures whose stories were to be read as allegories for contemporary political affairs. Where his depiction of Alexander Nevsky’s medieval conquest of German invaders warned audiences of the Third Reich’s rising threat in 1938, his two-part series on Ivan the Terrible likened the Tsar to Stalin himself – much to the dictator’s initial pleasure and later disapproval.

The creative limitations imposed on Eisenstein during this time may have kept his editing from reaching the avant-garde heights of his silent works, yet it is nevertheless a testament to his incredible craftsmanship that these films are still so cinematically ambitious. His renewed focus on mise-en-scene saw a slight shift towards expressionism, particularly in his production design, lighting, and blocking for Ivan the Terrible, while his exterior landscapes often featured low angles setting immaculately staged scenes against vast, grey skies.

This venture into sound cinema also saw Eisenstein invite two new collaborators into his fold. Sergei Prokofiev was already a famed composer of operas, ballets, and symphonies before this partnership, but through Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible he immortalised his name in the world of cinema too. Eisenstein’s casting of Nikolay Cherkasov as the titular roles of both films similarly cemented his status as a leading actor of Soviet cinema, showcasing his range by playing extremes of rousing courage and vain cruelty.

Eisenstein’s winning streak unfortunately came grinding to a halt after finishing Ivan the Terrible, Part II. His depiction of the historic ruler not only implied that Stalin was a ruthless tyrant, but also painted a vivid portrait of his own shifting relationship with the Soviet Union. He was no longer a filmmaker inspiring revolution through cinematic form, but rather a disillusioned artist simultaneously defying and reluctantly cooperating with an oppressive regime. Plans for Part III were immediately shelved, and Part II did not see the light of day until it was released in 1958 – ten years after Eisenstein passed away from a heart attack in 1948. Like so many artists who have worked under strict censorship laws, his output was limited, but still he carved out a legacy of montage editing that is woven into the very syntax of cinematic language.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1925 | Strike | MP |

| 1925 | Battleship Potemkin | MP |

| 1928 | October: Ten Days That Shook the World | MS |

| 1929 | The General Line | Unrated (Documentary) |

| 1938 | Alexander Nevsky | MS |

| 1944 | Ivan the Terrible, Part I | MS/MP |

| 1946 | Ivan the Terrible, Part II: The Boyars’ Plot | MS/MP |