Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. Playtime | 1967 |

| 2. Mon Oncle | 1958 |

| 3. Mr Hulot’s Holiday | 1953 |

| 4. Trafic | 1971 |

| 5. Jour de Fête | 1949 |

Best Film

Playtime. This easily belongs among the greatest displays of production design committed to film, perfectly merging Jacques Tati’s visual ambition, social satire, and sharply staged slapstick. The construction of Tativille is a staggering achievement on its own, blending a monochrome palette with harsh textures and sharp angles to build an artificial city that is both familiar and entirely the product of one whimsical, ingenious imagination. To then shoot it in wide shots that turn these bizarre edifices into perfect frames and obstacles for Tati’s physical gags is another cinematic triumph altogether. And then in considering the vignette narrative structure that whisks us between parts of the city and which gives this film its distinct form, it becomes apparent that Playtime is Tati’s best.

Most Overrated

Playtime. The TSPDT list gets it right in letting it sit at #1 of 1967, but having it at #49 of all time might be overly lofty praise. I would have it sitting in the #100-150 range – no insult to the film at all, but there are slightly greater cinematic achievements out there.

Most Underrated

Mon Oncle. Its ranking at #402 of all time on the TSPDT list isn’t terrible, but it should be sitting in the masterpiece range, around the top 250. Before Playtime, this was Tati’s best film, and shows off a wonderfully outlandish display of architecture sending up impractical modern design trends. There is also the sweet narrative through line of Monsieur Hulot’s relationship with his nephew, paying off in a heart-warming conclusion.

Gem to Spotlight

Trafic. This isn’t quite near the level of Tati’s top 3 films, but his resourcefulness here is truly impressive given that he was heading towards bankruptcy at this point in his career. Rather than using impressive architectural structures as the basis of his visual satire, here he hits on the ultimate paradox of an inept modern society – sitting in high-tech, metal boxes that are designed to drive us into the future, but which instead sit bumper-to-bumper in frustratingly stagnant lanes of traffic.

Key Collaborator

Alain Romans. This is not a particularly significant category for Tati though, who is not known for his collaborations. Still, it is worth noting Romans’ musical contributions to both Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle, developing relaxed, jazzy motifs that complement Tati’s laidback whimsy.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

A Spark of Inspiration

In the 1930s, long before his days as a director, Jacques Tati was performing in music halls across France, his act being described as “partly ballet and partly sport, partly satire and partly a charade.” It was also around this time that he began acting in shorts, introducing him to the world of film where he would eventually find his stride. His first effort at directing was the 1947 short, L’Ecole des facteurs, and while it was well-received, it is more notable than anything for providing the comedic foundation of his 1949 feature debut, Jour de Fête, which follows a similar line of comedic gags.

It was evident right away where Tati’s primary inspiration lies. Buster Keaton is written all across his deadpan expression and physics-defying stunts, as well as his dedication to using the entire frame set back in wide shots to play out gags. In his narrative structures of comedic vignettes and social critiques of modernity, Charlie Chaplin is very much present, though with a distinctly French twist. The invasion of American commercialism in small-town France is his primary satirical target in Jour de Fête, as he longs for simpler times where efficiency wasn’t the end goal. Like Chaplin, he is also a romantic at heart. His characters do not seek love, but every so often they come across a woman with similar innocent ideals, and the two find solace in each other while the rest of society keeps operating on its own nonsensical wavelength.

Of course, the silent cinema influence is most of all evident in the dialogue, or lack thereof. Rarely does it hold any key information we couldn’t glean from the visuals, and so instead it simply becomes part of his lush sound design, delivering character information through their vocal tones rather than their actual words. Around them, bells, squeaky chairs, and clacking shoes among an array of other everyday items fill in Tati’s intricate soundscapes, often accentuating gags with well-timed sound effects.

The Reign of Monsieur Hulot

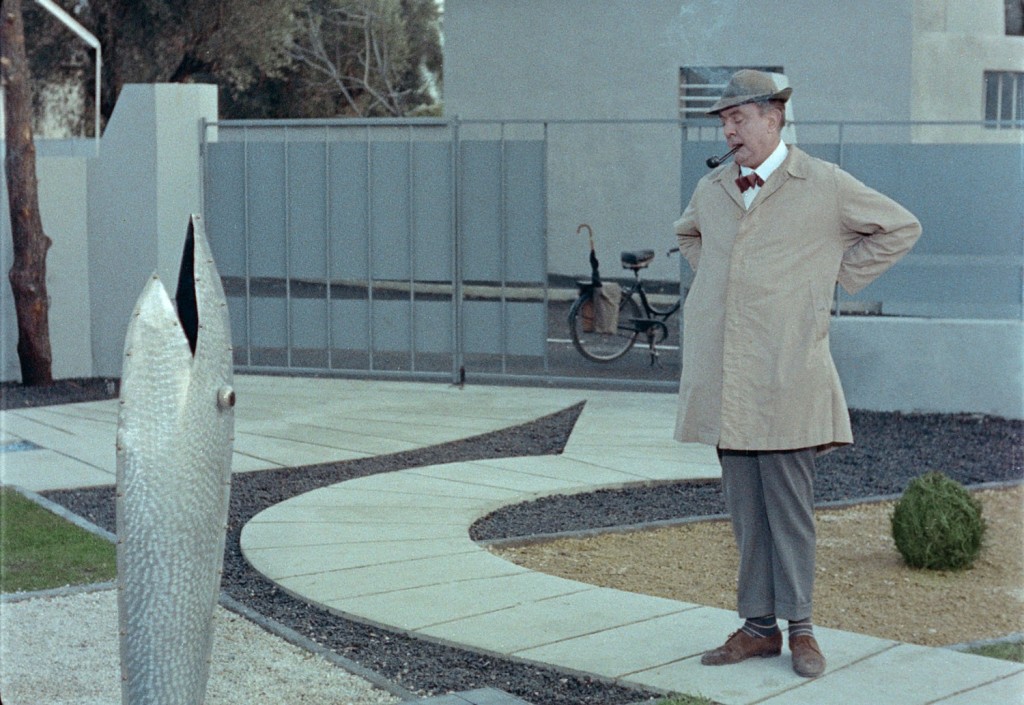

In 1953, perhaps the most significant cultural icon associated with Tati arrived. Monsieur Hulot is the bumbling, pipe-puffing, good-natured figure at the centre of all his greatest films, played by Tati himself. Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday solidified him as an extraordinary director, but the film is also greatly helped along by the presence of this distinctive character, whose peculiar fashion, long lurching strides, and childlike mannerisms sets him apart in any crowd. Just as you could draw a line directly from Chaplin’s Tramp to Tati’s Hulot, so too does Hulot become a direct inspiration on contemporary comedic characters – most of all Rowan Atkinson’s Mr Bean, whose silent antics are strongly reminiscent of Hulot’s ventures through a world he can’t quite comprehend.

There is also the development of his voice as a satirist in the 1950s, pursuing similar critiques of modernity that he initiated in Jour de Fête, though additionally targeting the superficial class structures, fashions, and technologies of mid-century France. Humanity’s efforts to progress as a society and grow more efficient ultimately has the opposite effect in Tati’s films, setting characters back with designs and systems that only serve to complicate their lives. The assembly line gag in Mon Oncle particularly calls to mind a strikingly similar one in Chaplin’s Modern Times, letting his inspiration peek through quite explicitly.

On a cinematic level, Tati’s greatest accomplishment through the 1950s and 60s was his architectural constructions, at times even rivalling Michelangelo Antonioni with his ambitious urban structures filling in as characters. Instead of using these to paint out wandering tales of isolated, wealthy Italians though, his constructions are brilliant oddities, often built on sets rather than shot on location. From the ramshackle, Dr Seuss-style apartment complex in Mon Oncle to the sprawling, monochrome city he created for Playtime, there is no understating his wildly impressive visions which land him among some of cinema history’s finest, most perfectionistic production designers. Every piece is curated, arranged, and shot with intensive purpose, which always comes back to the framing of characters in environments that are wildly beyond their control, and which diminish them in turn. To trace the progression of this through his career as well, it is clear that up until the 1970s he was trying to top his previous film in sheer scale, leading to his finest achievement of all in Playtime.

Bankruptcy and Decline

Tati was one of the few French filmmakers working in the 1960s to neither be grouped in with the French New Wave artists innovating cinema, nor be targeted by them for perpetuating the industry’s bland, middlebrow “Tradition de qualité”. In this way, he existed in his own bubble, coasting by on a unique style that calls back to cinema’s past more than it does push it into the future. As such, there was not much of a safety net protecting him from the massive financial failure of Playtime, which is less an indicator of its quality, and more of its extraordinarily large budget which could not be recouped.

1971’s Trafic is by no means a disappointment, but almost any film following the glorious Playtime would suffer in comparison. Though the visual work and production design is a step down, it remains thoroughly impressive for its sheer resourcefulness. Rather than reflecting characters in the towering architecture around them, cars are instead rendered as extensions of their quirks and foibles, and additionally carry on Tati’s criticisms of inept modern technology.

Sadly, Trafic was also the last onscreen appearance by Tati as Monsieur Hulot. Having failed to make a profit here too, Tati was driven to make his final film in 1974, Parade – also his first failure. There is something of a mannered feel to this, which isn’t surprising given that it is essentially a variety show of magicians, acrobats, clowns, and animals. Parade is the equivalent of a Netflix comedy special for Tati, and is far from cinematic or anywhere near the heights of his best work. It doesn’t help either that it was shot on fuzzy videotape that exposes the tiny budget he had to work with. For a director who once possessed such ridiculously monumental cinematic ambitions, it is an unfortunate film to bow out on.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1949 | Jour de Fête | R |

| 1953 | Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday | MS |

| 1958 | Mon Oncle | MP |

| 1967 | Playtime | MP |

| 1971 | Trafic | R/HR |

Reviews

Trafic (1971)

Trafic may not possess the sheer ambition of Jacques Tati’s previous films, but his resourcefulness remains remarkable, uncovering rich satire in recognising that the attempts of drivers trying to get somewhere while helplessly sitting in stagnant crowds of high-tech, metal boxes may be the ultimate paradox of an inept modern society.

Playtime (1967)

Jacques Tati’s bizarre, elaborate vision of Paris in Playtime is an intricately stacked construction of modernist architecture and comedic set pieces, sending up the soulless conformity of commercial society with a cinematic vision as monumentally ambitious as it is methodically delicate.

Mon Oncle (1958)

Keeping the spirit of silent cinema alive, Jacques Tati puts his flair for physicals gags and intricate architectural set pieces to use in Mon Oncle, sending up the consumerist culture of post-war France while offering hope in one playful, eccentric man this world isn’t as superficial, self-centred, or tangled as it seems.

Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953)

Whenever some force of political cynicism comes along to threaten the sweet innocence of Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, Jacques Tati may bite back with good humour, but his focus never strays from the sweet, childlike love of beaches, dress-up parties, ice cream, fire crackers, and summer vacations, effectively turning his film into the cinematic equivalent of…

Jour de Fête (1949)

Though Jour de Fête feels slightly limited without Jacques Tati’s bizarre displays of architecture to bounce his physical comedy off, he is still as resourceful as ever in both his acting and direction, whimsically sending up modern ideals of efficiency and progress when they begin to invade a tiny French village amid Bastille Day celebrations.