Martin Scorsese | 2hr 31min

At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter who is a police officer and who is a gangster in The Departed. These characters are destined to die awful deaths from the moment they commit themselves to one cause or the other, caught in the crosshairs of the Xs which Martin Scorsese slyly plants all through his mise-en-scene. They are framed as steel beams in industrial settings, patterned in hallway carpets, and cast on walls in thin strips of light, but most of all they are consistently present at the demises of each key player. Scorsese is not the first to adopt this motif, as it was previously used to similarly excellent effect in the original 1932 Scarface, but The Departed even more fully realises it as the thread binding each character to their sad, inescapable fates, dealing out equally cruel sentences with no regard for the loyalties they held in life.

Out of all of them, it is Irish-American mobster Frank Costello who recognises the futility of such allegiances, and plays the game the way that he alone sees fit – lasting as long as he can on pure self-preservation. Like so many others, he is marked by those deathly Xs right from his introduction, but his opening voiceover is also accompanied by darkness and camera angles which keep his face from view. Where we once reflected on Henry Hill’s childhood aspirations to be a gangster through his own eyes in Goodfellas, we now look back to the past through the perspective of the mentor grooming boys into his inner circle, revealing the sleazy underside of this lifestyle long before the children are old enough to see it for themselves. For all the cynicism present in these opening minutes though, Scorsese’s editing remains as sharp as ever, breezily whisking us through the parallel ascents of two young police officers, Billy Costigan and Colin Sullivan, whose overlapping lives precariously hang on the rapidly narrowing distance keeping them apart.

Dramatic irony runs thick through Scorsese’s narrative on many levels, leaving only the audience aware of the shared coincidences and quietly significant developments drawing the two men together. On one side, Costigan is ordered by his superiors to ingratiate himself with Frank’s gang, while on the other, Sullivan is sent by Frank to infiltrate the police. Both are aware that within their own organisations there is a rat leaking information, and yet the closer they get to their targets, the closer they are to being caught out themselves, and Scorsese mines the enthralling suspense of this self-defeating quest for all it is worth. Victory and subjugation go hand in hand for these men, while above them they are outmanoeuvred by a figure more cunning than either. Acting simultaneously as a crime boss and FBI informant, Frank will happily play to both sides of the aisle, demanding loyalty from others while refusing to give anyone his own. With the reveal of his duplicity comes a demonic, red glow that Scorsese casts over him in an opera theatre, detaching him even further from any semblance of the organised religion he outright rejects.

And yet despite all the complex machinations of this cat-and-mouse game, Scorsese draws a simple, powerful duality right down its centre, strongly suggesting traces of Michael Mann’s Heat in its study of two morally opposed minds obsessively circling each other. Like younger versions of Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, both Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon offer up gritty, highly-strung performances as men trying desperately to gain the approval of their superiors, and yet who also share a common understanding of each other.

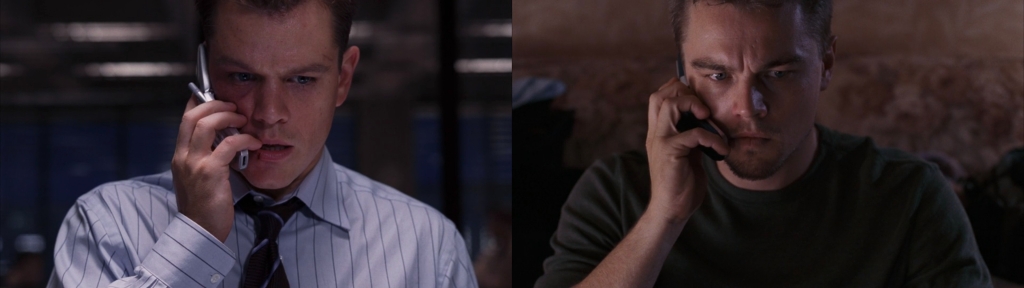

Evidently the paths to success as a man in either culture is paved with the same milestones of working hard, obeying orders, finding a girlfriend, and settling down, though the closeness of their trajectories is especially striking when they fall in love with the same woman, police psychiatrist Dr. Madolyn Madden. In effect, the two men share the same lives, and when they finally reach each other for the first time on the phone, a silent tension hangs in the air, drawn out by Scorsese’s suspenseful cutting to both sides of the call. As if realising that with the discovery of their adversary’s identity comes the exposure of their own, neither wants to be the first to speak, fearing the destruction of everything they have built for themselves.

For Costigan and Sullivan though, that single-minded compulsion to uncover the other rat first dominates all other survival instincts, and while The Departed does not exactly reach the stylistic heights of other Scorsese films, he still savours those thrilling set pieces which push them to their limits. Split diopters are used to great effect in building out the strained relationships of characters separated between layers of the frame, and the rock soundtrack heavily featuring Celtic punk band The Dropkick Murphys lends an aggressive Irish-American edge to their exploits. Among the most riveting sequences of the film though follows their chase outside a porn theatre where Scorsese throws them into smoke-filled alleyways of red and blue neon lights, setting up urban obstacles that offer plenty of hiding places and yet which keep both from catching glimpses of their opponent’s faces.

For all these wonderful visual flourishes though, The Departed is clearly operating more on the strength of its narrative than the lively experimentations we witnessed in Raging Bull or Taxi Driver. Its intricate construction of double-crosses and manipulations never get so convoluted as to become messy, but it rather propels this riveting story forward with impeccable pacing, leading these characters towards their inevitable graves. Frank may be the most purely evil of them all, and yet it is his nihilistic ethos which leaves the largest legacy, undermining every attempt to assert some grand sense of justice or meaning in the world. Just like Scorsese’s persistent Xs, the equal but opposite forces of Costigan and Sullivan essentially cancel each other out, and their realisations that they are not as exceptional as they would like to believe might almost be as shocking as the bullets which hopelessly reduce them to nothing.

The Departed is currently streaming on Binge, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

What did you think of Martin Sheen here? I know Drake disliked his performance but I’ve always liked what he does everytime I’ve seen this.

LikeLike

I don’t have any complaints about his performance, the only way he suffers is that I feel virtually everyone else is much stronger. I do appreciate Jack Nicholson here more than Drake does though, it’s an excellent piece of casting.

LikeLike