Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. Platform | 2000 |

| 2. Still Life | 2006 |

| 3. Ash is Purest White | 2018 |

| 4. The World | 2004 |

| 5. Xiao Wu | 1997 |

| 6. A Touch of Sin | 2013 |

| 7. Unknown Pleasures | 2002 |

| 8. Mountains May Depart | 2015 |

Best Film

Platform. Jia Zhangke’s follow-up to his promising debut, Xiao Wu, is sprawling and ambitious filmmaking. State performers searching for direction in the wake of China’s Cultural Revolution unfolds slowly and deliberately over ten years, taking an emphasis off plot and onto these wandering, disillusioned young characters. On top of that, Jia is following in the footsteps of Michelangelo Antonioni in his use of architecture, underscoring the emotional depth of his subtle drama. A defining piece of realism for the 21st century.

Most Overrated

Still Life. This isn’t outrageous though. TSPDT has it at #4 of its year and I would only be a few spots lower. There isn’t much to criticise here in this film – it is still Jia’s second best after Platform and reveals a new direction in his formal approach to structuring narratives into three-pronged segments.

Most Underrated

Ash is Purest White. Sitting at #21 of 2018 is bizarre. If it doesn’t belong in the top 10, it should at least be on the outskirts. It stands among Jia’s most structurally impressive films, as he instils its sound design, music, architecture, and colours with a soothing repetition that echoes down through all three chapters of its characters’ lives, both together and apart.

Gem to Spotlight

The World. Jia’s first step beyond the boundaries of strict realism, but only barely. The image of tourists and theme park workers towering over shrunken replicas of world monuments is surreal, and makes an acute statement on the cheapening effect of globalisation on human achievement.

Key Collaborator

Zhao Tao. Jia’s top actress appeared in eight of his films from 2000 to 2018, finally culminating in Ash is Purest White, which marked her greatest performance to date. There, she plays the lover of a mob boss across three chapters of her life, carrying an epic character study of feminine strength and its moulding in the fiery heat of adversity. She internalises that with hardy resilience – a common trait among many of her characters in Jia’s films, even while she embodies the isolation so present in his examinations of China’s modern landscapes.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

An Underground Movement

With increased censorship policies rising in China in the 1990s, there was a growing disillusionment with those state-funded films that neglected to depict the authentic lives and struggles of people as they actually were. The Sixth Generation of Chinese filmmakers thus came about as an underground movement led by Jia Zhangke, committed to raw realism – handheld cameras, location shooting, non-professional actors, all calling back to the Italian neorealists of the 1940s and 50s.

Debut and Breakthrough

Jia started his career at Beijing Film Academy where he made three short films, experimenting with documentary and narrative cinema. It was also there that he began work on his feature debut, Xiao Wu, set and filmed in 1997 during the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong. The time period and political landscape is marked with loud, public announcements declaring crackdowns on petty crime, threatening the welfare of the titular pickpocket.

It was ultimately Platform though, his follow-up effort, which made Jia an internationally renowned arthouse director, as he shifted his focus back to the 1980s to observe the gradual social changes in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. Jia’s frequent camera pans soak in the detail of dirtied interiors and rundown streets in both films, shooting in long takes that refuse to hurry the characters and stories along.

Pushing the Boundaries of Realism

Politics and globalisation have always remained at least in the background of all of Jia’s films, but while his earliest films might draw comparisons to Robert Rossellini in their authentic representations of Chinese workers, criminals, and slackers going about everyday life, it was about the mid-2000s that Jia began to throw in traces of fantasy. The final minutes of The World conclude with a pair of voiceovers seemingly playing out the thoughts of two dead bodies, and Still Life digs even deeper into such surreal allusions by using its hints at an extra-terrestrial invasion as metaphors for the destruction of an ancient Chinese village.

In 24 City, displaced workers and families who were previously involved in a once-standing airplane engine manufacturing facility now find themselves wrestling with a changing infrastructural and social landscape as it is demolished to make way for a complex of luxury apartments. Again, the grounding of realism is challenged in this experimental documentary that blends authentic and scripted stories, refusing to note the difference between the two.

Experimenting With Structure

As the 2010s arrive, Jia followed up on the formally segmented structure of Still Life with an anthology film in A Touch of Sin. In Mountains May Depart and Ash is Purest White, he similarly delivers a pair of of three-pronged narratives set across three different eras of Chinese culture. Even here though, there still remains a consistency in the significant Michelangelo Antonioni influence on his use of architecture and landforms to define characters, whether he is painting out a hardened spirit with a mountainous green volcano in Ash is Purest White or collapsing buildings around a man searching for stability in Still Life.

Jia is still active in the world of Chinese cinema, having recently made the short film Visit contemplating the COVID-19 pandemic, however there is no current news regarding his direction on future films.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1997 | Xiao Wu | R/HR |

| 2000 | Platform | MS |

| 2002 | Unknown Pleasures | R |

| 2004 | The World | HR |

| 2006 | Still Life | MS |

| 2008 | 24 City | Unrated (Documentary) |

| 2013 | A Touch of Sin | R |

| 2015 | Mountains May Depart | R |

| 2018 | Ash is Purest White | HR |

Reviews

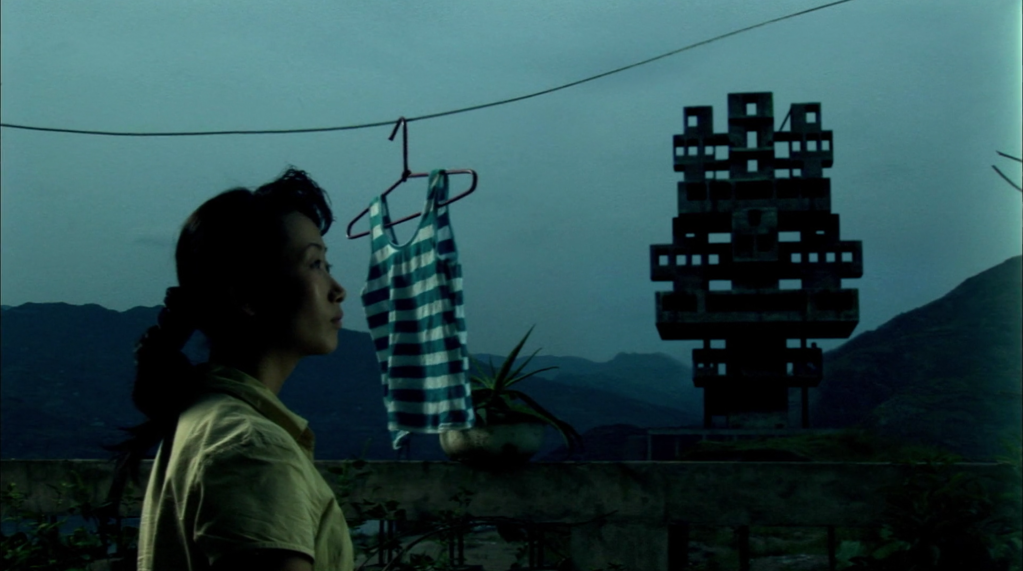

Ash is Purest White (2018)

Through Jia Zhangke’s interweaved motifs of colours and landforms in Ash is Purest White, he creates an epic character study of feminine strength, and its moulding in the fiery heat of adversity.

Mountains May Depart (2015)

Mountains May Depart marks Jia Zhangke’s most significant withdrawal from his distinctive, neorealist style, and although the film is a little weaker for it, he still finds a deep poignancy in the widening generation gap separating China’s past from its future.

A Touch of Sin (2013)

Four loosely connected episodes of violence based on real Chinese news stories come together in a Touch of Sin to sketch out a landscape of anger and frustration, as Jia Zhangke pushes the boundaries of his usual neo-realistic style until they start to overlap with traditional crime thriller conventions.

24 City (2008)

Jia Zhangke remains as engaged in the globalisation of industrial China as ever with his foray into documentary filmmaking, as 24 City’s experimental blend of authentic and scripted interviews suggest a shift into an uncertain, postmodern future where luxurious, high-rise apartments displace tight-knit working communities.

Still Life (2006)

Through the violent demolition of an ancient Chinese village in Still Life, Jia Zhangke brings about an apocalyptic vision of modernity and globalisation, pushing the boundaries of neorealism with an eerie edge of science-fiction imagery.

The World (2004)

There is a beautiful, architectural surrealism to the miniature replicas of world-famous monuments that feature in The World, as the theme park where Jia Zhangke sets his film shrinks these landmarks down to a size that makes both tourists and staff look like giants, and simultaneously criticises a globalised Chinese culture that allows for such…

Unknown Pleasures (2002)

While Jia Zhangke grounds Unknown Pleasures in a grim reality dominated by derelict architecture and television sets, his young adult characters try to find some comfort in the philosophy to “do what feels good”, even if these ancient words are little more than a despairing assertion of meek independence in the face of a constrained,…

Platform (2000)

Though we can appreciate the immediate impact of Jia Zhangke’s stark, minimalistic aesthetics in painting out a social landscape in decline, the formally ambitious construction of China over a ten-year span reveals an accumulation of small changes set in motion by an increasingly globalising culture, slowly eroding the value of art, tradition, and relationships.

Xiao Wu (1997)

Taking rich inspiration from the Italian neorealists who preceded him by roughly fifty years, Jia Zhangke turns his camera to the streets of a provincial Chinese town during a particularly harsh crackdown on crime, tracking pickpocket Xiao Wu through a shifting culture that he no longer recognises.

Love this format Declan, looks so neat and tidy, packs all the information into one page.

LikeLike

Thanks Harry! I’ve been sitting on this since my Jia Zhangke study but wanted to wait to put it out with a few other director pages, so I’ve got a couple more coming out over the next week or so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful site and a wonderful page. Which director is next?

LikeLike

Thanks! Kieslowski up next in a few days, and then after that I’ve got one on Tati. I actually ended up going into more detail for them as well.

LikeLike